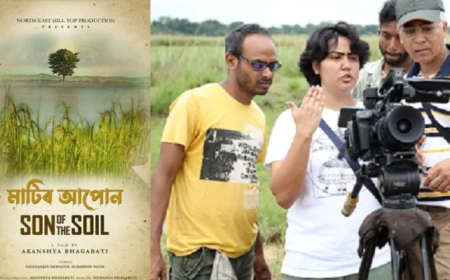

An interview with Slaves of the Empire (2024) filmmaker Rajesh James

Dipankar Sarkar provides an interview based review of Rajesh James' documentary, "Slaves of the Empire"

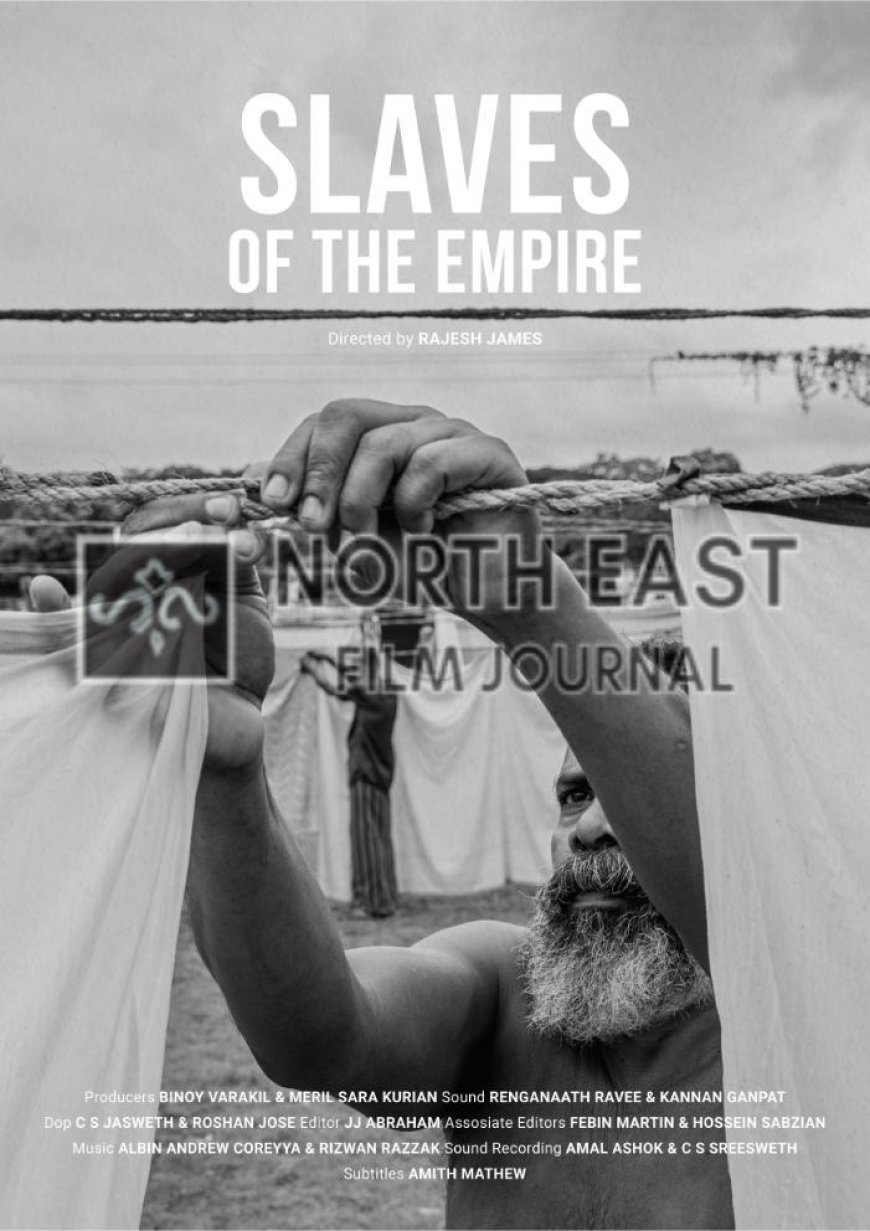

Rajesh James' documentary, Slaves of the Empire, depicts the lives of washermen from the Vannar caste of Tamil Nadu brought to Kerala by the Dutch rulers. The narrative subtly portrays the dynamics and camaraderie between the various members of the washermen community. The highs and lows they experience help them form an unconditional bond and overcome the grind of existence with the ghettos of Dhobi Khana in Fort Kochi.

Slaves of the Empire was selected in the competition section of Long Documentary at IDSFFK 2024.

In this interview, James talks about his journey as a filmmaker, his aesthetic choice of shooting in black and white, and the oppressive history of Kerala during the regime of Portuguese rulers.

What inspired you to make the documentary?

When I began making films, I had no clear direction. I frequented Dhobi Khana in Fort Kochi whenever I had free time, immersing myself in the place by researching its history and getting to know the people. I felt it was important to fully understand the environment before starting any filming. I don't rush into projects; instead, I let ideas percolate and only pursue them if they linger and captivate me. Dhobi Khana was one such subject that resonated deeply with me over time. Through this documentary, I wanted to explore Kochi's overlooked history through the lens of a community enslaved by the Dutch and it took nearly four years to complete.

When you began the shooting, were Rajan, Pratti, Rajashekharan, and Selvaraj always the four central characters of the documentary?

Though I was welcomed in Dhobi Khana, it took nearly six months to gain the trust of the washermen. The initial footage looked lifeless. But over time, I was able to capture the essence I was looking for. Characters like Rajashekharan, Rjan, and Selvaraj became a part of the narrative by chance. Selvaraj, for instance, was initially reserved and spoke infrequently. Yet when he did, it was meaningful and revealing. In documentary filmmaking, premeditated plans often fall short. I would like to quote Hitchcock- In fiction, the director controls the narrative, but in documentaries, the subjects guide the story.

Can you talk about the aspect ratio and black-and-white images of the documentary?

While shooting in Dhobi Khana, I felt the space was confined. It was like an old building with a lot of distracting visual noises. My cameraman, C.S. Jasweth suggested we consider shooting in black and white. The suggestion resonated with me immediately as I am fascinated by the films of Béla Tarr. As we began shooting, the decision provided the documentary with the visual contrast we needed between the white clothes and the bare bodies of the washerman.

The aspect ratio was finalized when J.J. Abraham came on board as the editor. His suggestions and sample edits convinced me that it was the right choice. Although we faced some challenges because we hadn't shot all scenes in the 4:3 aspect ratio and had to reshoot, once we adjusted, everything fell into place.

Although the laundry workers reside in Kerala, superstar Rajinikanth plays a key role in their lives. Through the medium of cinema are they retaining their Tamil identity?

I was introduced to cinema by watching popular films and I had some reservations about them. But the washermen of Dhobi Khana offered me a new perspective. For them, Tamil films and songs help them maintain their Tamil identity while they are residing in Kerala, where Malayalam is the native language. Popular cinema, in this context, becomes a bridge to their past, linking them to the places and people they left behind.

I developed a connection with him through film. To build rapport, I watched many Rajinikanth movies, immersing myself in his world. I was astounded by Selvaraj's deep passion and extensive knowledge of Tamil cinema. He has watched all of Rajinikanth's films numerous times recalls every detail, and often engages in discussions about the subtleties of these films. Many other laundry workers share similar enthusiasm. Whether through songs, posters, or dialogue, cinema is ever-present in Dhobi Khana.

Does belonging to the Vannar caste still influence the social conditions of the washermen?

The Dutch brought the Vannars to Fort Kochi in the early 18th century as slaves to launder their uniforms. So, from their oppressive past, they have come a long way, and today they are living a life of dignity, and are fully aware of their rights and actively advocating for them. Their experiences and history provide important lessons for suffering communities worldwide.

I have deliberately chosen the title 'Slaves of the Empire' for the documentary. Kerala has a progressive image that often overshadows its darker history. Reading the works of historian Vinil Paul had a profound affected on me. I was stunned to learn that slavery existed in Kerala as well, not just in Europe or America. This buried history is something we walk over daily and is either forgotten or ignored. So, I aimed to bring this hidden history to light, which the ruling governments continued to exploit and dispossess, especially after the Independence of India. These untold stories of exploitation need to be recognized.

How important is it for you to be selected in the competitive section of IDSFFK?

For an emerging filmmaker like me, IDSFFK holds immense significance. It is an annually held documentary and short film festival in the country that is funded by the government and rarely faces any censorship. Unlike MIFF, which has become increasingly propagandistic, IDSFFK maintains a critical space where films can even critique the very government that supports the festival.

Now for over a decade, I have been attending IDSFFK, and this year was special because my documentary was in the competition section. It was an honour to have my documentary screened alongside prominent filmmakers like Anand Patwardhan and Nishtha Jain. Moreover, it is always an incredible experience to have a screening filled with lively audiences fully immersed in their viewing experiences.

*****

What's Your Reaction?