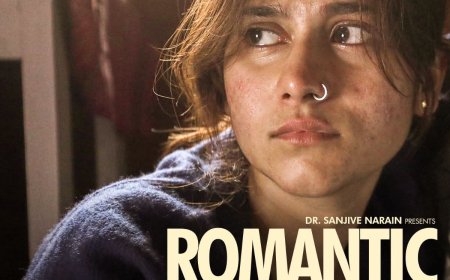

Interview: Shilpika Bordoloi

In Mau: The Spirit Dreams of Cheraw, director Shilpika Bordoloi offers a hauntingly poetic meditation on memory, loss, and the resilience of indigenous culture. Set in Mizoram, the film reimagines the Cheraw (bamboo dance) as a ritual to honour and pacify the spirit of a mother who dies in childbirth, a forgotten story revived through movement, sound, and spiritual memory.

Mau: The Spirit Dreams of Cheraw received the Best Debut Film of a Director at the 71st National Film Awards, marking a significant recognition of Bordoloi’s unique approach to storytelling and film form.

In this interview, she talks about her creative process, the role of somatic filmmaking, and the deeper cultural, ecological, and creative energy that flows through her work.

Dipankar Sarkar. In Mau: The Spirit Dreams of Cheraw, you draw a powerful connection between bamboo, the Cheraw dance, and the geopolitical history of Mizoram. How did you first come across this connection, and what inspired you to explore it as a central thread in the film?

Shilpika Bordoloi. I envisioned this film to intersect performance, memory, and the natural world to shape a sensory experience. The film departs from linear documentary formats and embraces a somatic structure, rooted in ritual, landscape, and embodied history. My approach is informed by the notion that stories are not always spoken; they are carried in movement, silence, breath, and the ecological intelligence of the land.

I rediscovered an enduring connection with Bamboo on returning to Assam in 2012. I saw bamboo bridges, boats, houses in villages - structures that, while temporary in form, carried generations of knowledge. They did not promise permanence and instead, they spoke of a different kind of time. A time that knows loss, decay, and return. Even as bamboo weathers and loses strength, people continue to build with it, knowing what they make will be rebuilt.

I have been working with Bamboo as a co-creator for a few years now. So the first step was the acceptance of this knowledge that my film is about Bamboo. As I researched Bamboo as a material in the context of Climate Action, a whole world came up, and Bamboo became a teacher, not just in form, but in feeling.

The issue of displacement has been a festering concern of cultural conflict in North-east India for years. I had begun working in Assam, but then I read how in Mizoram, the historical big famine of 1959, Mautam, caused by the flowering of the common bamboo called Mautak, not only gave birth to political movements but also led to the creation of the state of Mizoram. This was the tip of an iceberg for me and a calling. My lens was to see humans not as individuals but as a species travelling through the birth-to-death cycle as non-humans.

I landed up in Mizoram with my DOP and conversations with musicians, dancers, activists, environmentalists and researchers, primarily Mr. P.C. Laldirinka, who is pursuing his PhD on this very subject, helped to join the dots about the story of this film and the forgotten history of Cheraw.

Many personal causes form the underlying reasons behind this. For example, the film responds to maternal themes, which have long been associated with ecology through the narrative of Mother Earth and theories of ecofeminism. These theories highlight the connection between the subjugation of women and the exploitation of nature by capitalist and patriarchal hegemonies. We wish to propose that this loss of memory of the mother is an intergenerational loss, which also directs attention to the loss of culture and hence the larger ecological crisis, that we feel is not isolated but intersectional.

Dipankar Sarkar. In your director’s statement, you describe your process as somatic filmmaking. How did this approach shape the making of this film, especially in how you worked with dancers, performers, and the local community?

Shilpika Bordoloi. I am a dancer and have had a journey through forms of Indian Classical Dances, Martial Arts, Yoga, Physical Theatre and Experimental Dance. Body Wisdom is my Umbrella work, and Somatic Body is my research.

My process is Ethnographic too, and in different mediums of Art and Education, I have had a history of working with communities with many, particularly the Mising Community in Assam. This work has gone deeper since I founded Brahmaputra Cultural Foundation in 2013.

Creating movement on location in Anthropological Films required a process of dipping into knowing of other kinds that are not considered Academic, like theories used by others or arrived at by predecessor researchers. Being on location to dance on the spot requires observation and an alchemist-like quality to immediately transform that knowledge into an abstract or specific expression of that in the body. The biggest technique or instrument here is intuition. To go to a site mostly based on intuition and perhaps choose also for cinematic reasons, but mostly for intuitive knowledge. To make plans to come back to develop one motif discovered in one site because it sensed in a way that integrated the story, narrative or emerging script. Many dancers choreograph a sequence in the studio and go to locate it in natural surroundings. That, in my gaze, is a dance video shoot, nothing anthropological in it. But the script might require the usage of a specific dance form in a location, and that is something I value. To retain a form of dance in a context and present it in a way that mirrors the community. It has to move beyond the individual impression of the filmmaker to ensure the community is preserved, respected and shown in the best possible light. The YMA Spiritual Dance Troupe were amazing, and my production locally was efficiently done by Ramtea. We spent time together sharing our lives and beliefs, and food. In Aizawl, we also met this fantastic musician Tetea. This film was only possible because of the generosity of the Mizo community, who opened their hearts, homes, and history to me during the making of this film. Their generosity of spirit, cultural pride, and graceful dignity made it possible to bring this story to light in a manner that honours its origin. The stories, rituals, and rhythms that shaped this documentary are not mine alone—they are a shared gift.

Dipankar Sarkar. How did you approach the visual design of the film to translate a deeply internal and spiritual experience into something cinematic?

Shilpika Bordoloi. The camera is not a distant observer; it moves with breath and intention, becoming a participant in the scenes it captures. The camera also performs as a choreographer along with the performer in front of it. This kind of collaboration between cinematography and choreography is based on questions that I am exploring about the long tradition of dancing in the landscape, and perspective as a dancer in front of the camera and a director behind the camera. I believe my approach can capture the imagination of the audience differently. I love long takes, experimental depth of field, and macro details and textures.

At every point, the approach draws on the emerging form of visual anthropology that I am working with. It occupies a space where it can acknowledge the privilege of connecting in the immediate and express the story in a way that is intimate, political, and has possibilities for a different kind of solidarity because the expression can resonate at an inner level as opposed to being understood purely intellectually.

Dipankar Sarkar. The film suggests that the loss of maternal memory passed down through generations can lead to a cultural crisis. How do you see this unfolding in present-day Mizoram or elsewhere in Northeast India?

Shilpika Bordoloi. For me, the biggest story of our times is climate and cultural changes, and I feel that the complexity and challenge of the climate emergency needs to be addressed. We are making rapid infrastructural changes all over. In my hometown of Jorhat, age-old trees are cut without a single thought. Empty spaces and green cover within the cities and towns are not planned. So many trees were cut but not enough planted. In many countries and cultures people think before chopping off a tree that has seen generations. We are changing the course of our rivers, building so much infrastructure on them. It is so alarming and we also hear of inevitable catastrophes because of it. Cutting a tree is connected to the loss of a ritual with i,t, and we lose our stories, dances, songs, food and everything else that makes culture. Everything is at stake today. Indigenous knowledge is about listening to nature as much as they listen to us. I see us living today in a world where the local knowledge systems are disappearing.

We need to find new contexts, partners and collaborators. In this film I and my collaborators have come together to revisit our practice, redefine our relationship to community, to earth and nature, so that new practices emerge. How do we start to renegotiate existing hierarchies and marginalization of the non-human from humans? How do we inspire connection, curiosity, insight and empowerment for change?

Dipankar Sarkar. What role do you think films like this play in preserving indigenous knowledge systems while also helping them evolve in current times?

Shilpika Bordoloi. I believe artistic portrayals and films can contribute towards reflection, a certain “placement”. Climate and culture change is a tangible emergency that surrounds us today, and within this wide issue, I am seeking some insights. To begin with, how can I place them? Who is it that needs placement? In this way of working, I take my responsibility seriously and view my subjects and stories as my form of climate action and cultural action. They also become an archive. The Indigenous knowledge systems will be re-seen and heard and maybe or hopefully in some ways it’s a re-birth of a memory to become a lived experience, alive in the present for the audience.

Dipankar Sarkar. Mau: The Spirit Dreams of Cheraw has won the Best Debut Film of a Director at the 71st National Film Awards. How important is this recognition for you personally and for the stories you're trying to tell through your work?

Shilpika Bordoloi. The way I live and work it is a movement of emergent practice. As a practitioner, an award has never been a goal in the moment of production. But receiving this news came as a moment of grace, of also experiencing the communal joy of my well-wishers and family. That has undoubtedly multiplied my own state of happiness on receiving the news of the award.

When I was making Mau, I never imagined the afterlife of the film. Mau’s financier was a patron who was not keen to be involved in any way with production and post-production. We just shared the common cause of climate story and action. And my team never spoke about submitting the film to different festivals. I was a first-time filmmaker, taking my ethnographic understanding, integrating practices with the lens. Even though I was the inevitable producer, I did not think of the business aspect. I was just fuelled by this exploration of the form of the film, by maternal histories and feminism and taking this connection forward with Indigenous peoples and looking at nature in non-patriarchal ways. When I showed it to friends during the drafts of editing process, these suggestions came from sending it out, showing it to the world. I was and I still am intrigued by how audiences look at it and I think this is where the filmmaker in me meets the anthropologist with the shared intention of raising the questions that affect the community, by trying to find a road that is about a gaze of the right impact to community and artistic practice. I wish for this film to be seen by many audiences today.

Mau has taught me about the ecosystem of films, about festivals, and about awards. I really feel immensely grateful to Bamboo, Cheraw Dance, the community of Mizoram and the beautiful Mau team. Also very grateful to the Jury. I am happy to receive this recognition. I feel empowered and affirmed to have won this award on pure merit, through practices lived and embodied. So it is a big affirmation for me to walk this path. It is a moment of breathing with a certain ease, knowing that I and my form have an audience. I would love to find a business producer now and hopefully, this recognition brings me the right people, funds and pathways to bring out the other stories that can't wait to be heard and seen and felt.

What's Your Reaction?