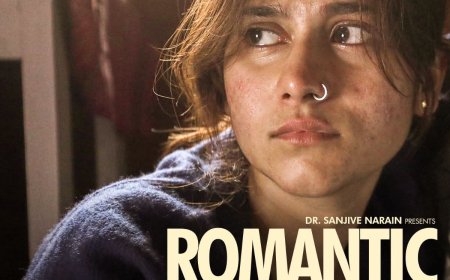

An interview with Adhiraj Kashyap, a student of FTII, Pune

Dipankar Sarkar talks with the filmmaker, Adhiraj Kashyap on his recent documentary . "My intention was to observe life in the village without being intrusive even for a moment, and through that try to gently bring out the realities of that space", says Adhiraj.

Noted Indian film critic and an alumnus of FTII, Pune Dipankar Sarkar interviews Adhiraj Kashyap, a young Indian filmmaker.

Adhiraj Kashyap’s documentary Dongarachya Kushit (In the Lap of the Mountain, 2022) revolves around the Adivasi people in the village of Golegaon, Maharastra, who are resisting oppression from the upper caste dynamics and hierarchy prevalent in the region to assert their position in a society of which they have been a part for generations. It is an evocative inquiry into the subject that surpasses documentation and involves the audience through its lyrical excursion. The documentary was selected for the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival, 2023.

I recently spoke to the filmmaker and discussed the process that went into the making of this expressive documentary.

How did you come across the idea of the documentary?

The documentary was made as a student project in FTII in our fourth semester, which is totally dedicated to the learning and making of non-fiction films. As part of that process, some of the students were taken to a certain place called Junnar in Maharashtra, around where we had to look for our potential “subjects” on which we wanted to make our documentaries on. During our stay at Junnar, when all of us were roaming around individually, I happened to visit the famous Lenyadri temple quite a few times. I started interacting with the people who worked there to know more about that place and learned that most of them were from the neighbouring Adivasi village Golegaon and have been staying there for generations. My interactions with the people started to grow organically day by day, not because I was looking for a “topic” to make a film on, but I genuinely started developing an earnest bond with them naturally. The first thing that attracted my attention was how proudly they talked about their ancestral tradition of the Doli (palanquin) service and how, with time, it has become an integral part of their identity as a community. Slowly and steadily, when some of them loosened up in front of me and became more friendly, they were able to express about their perennial fight with caste hierarchy and discrimination. The very fact that they had to struggle in their own place to hold onto their traditions and assert their own individual identity as a community even after being a vast majority in the village made me extremely intrigued to explore more, and that’s how the idea of the documentary arose. My intention was to observe life in the village without being intrusive even for a moment, and through that try to gently bring out the realities of that space.

The beginning of the documentary gives the impression that it is an account of individuals who offer palanquin services to the elderly devotees at the temple. But as it progresses, we realise that it is about the adivasi community of the Golegaon region of Pune district. How did you arrive at this structure?

As I mentioned earlier, the first thing that got me into the subject matter was the Palanquin service the Adivasi people of Golegaon have been providing to devotees since ages. So, I felt that it would be a good entry point for the audience to explore the place and its people the way it was for me. At no point was I shying away from the fact that I was an outsider in that place, and in the documentary as well, I wanted to retain the nature of how I, as a filmmaker and as a person, was seeing and interacting with those people. The decision to start the film that way was not made at the editing table but during the research process itself. I was more sure of my decision while shooting, as the film started taking concrete shape in my head.

You have also touched upon the theme of upper caste politics in the documentary, where we are informed that only individuals from the Mali and Maratha communities are part of the temple trust. Individuals from the Adivasi community hold no position in the trust. What are the caste dynamics in the region?

The caste dynamics in the region is the focal point of the film and also one of the primary reasons I wanted myself to be associated with the subject. The caste hierarchy in Golegaon and the discrimination that arises due to it is nothing different from the rest of the country. Even after being the vast majority in the village, the Adivasi people have been subjected to various inequities over generations. Not only are they neglected in the formation of the Trust for the temple, even though they have been serving in that place for generations, but they also haven’t escaped caste-based bigotry in other shades of daily life. As mentioned in the film, the limited green fields that can be seen in and around the village in the dry seasons belong to the upper caste people. And the irony is that the very people who make their farmlands green are Adivasis, mostly women, who work there as daily wage labourers. Adivasi people can’t farm even after having lands of their own due to their inability to afford irrigation.

Vignettes and quotidian activities of rural life form the narrative blocks of the film. What was your visual approach to the film?

As I mentioned earlier, my primary intention was to observe life in general in the village, trying my best not to be intrusive at any point. I thought that there had to be a delicate gentleness in the visual approach, filled with an empathetic gaze. Being an outsider, and that too not from their caste, I was also aware of the fact that at no point I wanted the gaze to turn "sympathetic" and "downward." That would defeat the whole purpose of me wanting to make this film in the first place. When I was discussing the visual language of the film with my cinematographer, Sejal, these were the first things I mentioned to her. We discussed a lot before shooting about how to have a unified visual language in the film and were quite sure of the fact that we wanted to be as close to our characters as possible while shooting them in some of the scenes. We were also leaning more towards using the tripod in most of the places instead of hand-held shots (all of our shots in the film eventually ended up being shots on the tripod). Our lensing choices were also driven by these ideas. But some things did change during the shoot, and in non-fiction, a filmmaker has to allow that. Otherwise, it runs the risk of being too constructed. Whatever felt organic and natural at that moment, we were trying to move ahead with that gut. No matter how many discussions you have about the visual language of a documentary, if one cannot capture the moment with honesty and care, none of it will reflect. So, a lot of the credit goes to my cinematographer, Sejal, and what she brought to the visual approach. Her inherent instinct for framing people in that space added massively to what each shot ended up evoking. And the rapport I share with her made the process a lot easier, as many times she could feel what I wanted in the frame and how I wanted it without me even having to say it.

You have not listed the name of any individual featured throughout the documentary. Was it a conscious decision?

You may say that it was sort of a conscious decision. I was very sure from the beginning that the film I was trying to make was about the community at large and not individuals. Even though there is one character (Jeetendra Bhalekar) in the film we spend most of the time with, I didn’t want it to become about him. I realised that in a 20-minute documentary (that was the maximum limit for the students for this particular project), I needed to have a sort of central character as a device to tap into the things I wanted to explore. But my idea was to open up the film to the larger community from an individual perspective. Using the sense of "self", I wanted to move towards the idea of the "collective". Had the film been longer, there would definitely have been more characters I would have loved to engage intimately with. But naming the list of individuals might have underlined the sense of "individual," which I didn’t want in the film. It would have taken away from the collective dreams, desires, aspirations, and struggles of the community I wanted to focus on.

How much did the process of editing help shape the documentary?

From my limited experience, I can say for sure that documentaries are very much shaped up at the editing table. Of course, it depends on the kind of film one is making, but editing does play a significant role in the making of non-fiction films, and ours was no exception. The initial idea I had for the film and eventually what we ended up making did not coincide completely. My initial idea was to focus more on the similarities and dissimilarities in the approaches to life of two different generations in the community. There was another primary younger character we shot a lot with to tap into the outlook of the younger people from the Adivasi village. But in the edit table, it wasn’t fitting well and seemed very disjointed. Also, due to the limitations of the duration we had for the project, I restricted the way I approached the film. During the edit, a lot of things had to be left out that I otherwise would have loved to include. Those portions would have added more layers and helped the film have more depth in general. Moreover, my editor, Somprakash, and I realised during the process that a lot of the things we initially thought weren’t working and hence took decisions to serve the film in the best way possible. There were also important inputs from Sneha (the sound designer of the film) regarding the structure before it went to the sound design process. I also had to loosen up on the initial edit structure I had in mind in order to make the film more coherent and pointed.

As the documentary nears an end, a character from the adivasi community informs us that the present generation is better off than their ancestors because they are more educated, which prevents them from being cheated and exploited. But in reality, will the dominance of the upper caste over the adivasis ever face resistance?

Speaking of this particular community and this particular village, there is more resistance now than ever. Obviously, being a person from another place and another community who does not understand the nitty-gritty of the discrimination they have faced for generations, I wouldn’t be the perfect person to answer about the intricacies of it, but the amount of time I had spent with them made me realise that at least a few from the younger generation understood the importance of education and the awareness it could bring to their community. But speaking of the dominance of the upper caste in a larger sense, I don’t think things are anywhere near perfect. The societal structure in our country works in a way that does not, or rather, does not want to, wash away caste-based hierarchy. The privileged, including us, have rarely gotten out of their comfort zones to actually work towards a structural change in society. It feels like the hierarchy and the privilege it allows the upper caste people are inherently ingrained in their genes, and they are far from wanting to get rid of them. And the same goes for governance, even after 75 years of independence. So, in that aspect, even after growth in education and resistance, I don’t really see a societal "system" in place that allows the lower caste people to thrive.

The documentary begins in the morning and ends with shots of the night. Is this the kind of circularity you wanted to have in the structure?

I had this structure of playing with the idea of day and night right from the moment I conceived the film in my mind. There are two points in the film where night shots are included: one comes somewhere in the middle and the other towards the end. I felt that for the audience to feel a part of that place, I needed to take them on a journey. So, more than circularity, I think seeing the nightlife in that place, which is very different from the energy during the day, works subconsciously on the mind of the audience and evokes a gentle sense of actually spending time at that place.

Dongarachya Kushit has been selected for the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival. How important is it to you and your team?

I believe film festivals are not a marker of the quality of any film, but I would be lying if I said that I wasn’t excited when I got the news of our film being selected, and that too in the International Competition section. The entire team consists of young film professionals taking baby steps in this field, and our student project being selected at one of the oldest and most prestigious film festivals in the world is a huge boost to our confidence. Considering the fact that it is the only Indian presence this year at the festival, it also feels good to represent the country and Indian cinema in some way or another on an international stage. Usually, film programmers, curators, critics, and film enthusiasts from all over the world are always involved with these big festivals, and this gives our film an opportunity to be seen and discussed on a global platform, which helps the film reach an audience it otherwise wouldn't have.

Lastly, now that you're in your final year, what are you more inclined towards—fiction or non-fiction filmmaking?

Making this particular film made me realise that non-fiction is more about you, the person, than the filmmaker. It opened up a lot of things about myself that I probably wouldn’t have tapped into otherwise. I’ve also realised that it is much tougher than fiction, at least for me at this point in my life. But I would want to keep working on myself and continue making documentaries. Exploring the works of Viktor Kossakovsky, Wang Bing, Federick Wiseman, Anand Patwardhan, Joshua Oppenheimer, Chantal Akerman, Agnes Varda, etc. has opened up the possibilities of non-fiction for me, even though it is quite late in my life. But the major influences I’ve always had that are, in a way, responsible for me wanting to become a filmmaker in the first place are fiction films. Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Kiarostami, Tarkovsky, Lucrecia Martel, Claire Denis, Bela Tarr, Angelopoulos, Lee Chang-Dong, Mikio Naruse, Fellini, Edward Yang, Antonioni, Martin Scorsese, Satyajit Ray, Tsai Ming-Liang, Andrey Zvyaginetsev, etc. Consciously or subconsciously, I’ve derived a lot from them and many more, and I feel a major portion of who I am as a filmmaker today is shaped by that, and I don’t think that will ever go away. So hopefully, I will be able to keep shifting between fiction and non-fiction and explore new things in that process.

***

What's Your Reaction?