All We Imagine As Light : Is Mumbai an Illusion, or is it a Dream?

Renowned film critic and National Award-winning author, Dr. Shoma A. Chatterji, offers an insightful and evocative review of the cinematic masterpiece, *All We Imagine As Light*.

When three ordinary women like Prabha, Anu or Parvati find themselves ‘displaced’, they do not immigrate as individuals who exist and function in an emotional, cultural and social vacuum. They bring along with them, the baggage of their past into their present, a past that has shaped them into how and how much they will imbibe and internalize the spirit of the new environment into their present that will determine, in a manner of speaking, their future and their destiny. All this and much more, comes across simply yet beautifully in Payal Kapadia’s debut feature All We Imagine as Light which bagged the Grand Prix at Cannes earlier this year, becoming the first Indian film to be so honoured.

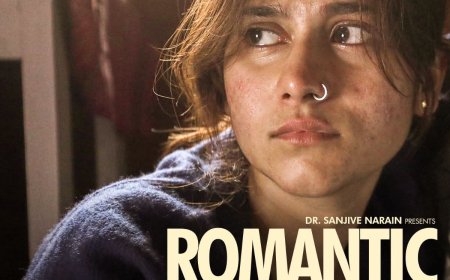

Prabha (Kani Kusruti) and Anu (Divya Prabha) are originally from some Kerala village and their roots in some way, function as a binding force. Parvati (Chhaya Kadam) a widow in her mid-forties, is originally from a seaside village in Maharastra but has been living in Mumbai for more than 20 years. While Prabha and Anu work as nurses in a maternity hospital, Parvati is a cleaning woman in the same hospital. Prabha and Anu share an apology of a flat while Parvati lives in a shanty which is threatened with demolition by a builder, one among thousands of builders whose sole aim in life is to puncture the Mumbai skyline with tall skyscrapers and render the poorest of the poor, homeless.

Parvati does not want to surrender to threats but she has no document to prove legal ownership of her shanty. Prabha’s attempts to help her with legal advice comes to naught. So, she manages to get a cook’s job back in her seaside village in the interiors of Maharasthra and decides to leave Mumbai. Prabha and Anu decide to go along to help her settle in the new place.

None of these three women are ambitious or career-minded with bright dreams of their future. Nor are they feminists or man-haters. They are ordinary individuals forever coping with their present without any grumbles or anger or frustration or tears or even dreams of a bright future. Prabha is married but only in name as her husband flew to Germany never to come back. She smiles little and talks even less but enjoys standing on the footboard of the local train to watch the teeming crowds out on the streets on her way to the hospital or on her way back. She can see the running trains from the window of her tiny room where rarely, she looks into the mirror to look at herself and is worried about the pranks of Anu who takes every opportunity to meet her Muslim boyfriend Shiaz for a quick “roll in the hay”. Anu even buys a burqua on Shiaz’s advice to meet him at his home when his parents are away. “Why should I wear a burqua?” she asks him and he explains that since they live in a Musim ghetto, the burqua will stave off eager neighbours’ trying to identify her by her communal identity.

The Mumbai local trains, said to be perhaps the largest in the world, function like the spine of the city, and the film, rushing through the tracks and through stations till we can see in it, a significant character defining the identity of the city. The sole sign of a communal feature comes across in the scene showing the Ganapati Visarjan with teeming crowds walking along the streets signifying that the first half of the film is shot during the heavy rains in Mumbai. The trains are a metaphor for speed, a constant state of movement on the one hand and a physical reality on the other.

Prabha is friendly with a junior doctor in her hospital. Prabha has learnt Hindi quite well but the doctor, also a Keralite, has not been able to pick up the language and feels drawn to this young woman. But when he approaches her to say that he will change his decision to resign if Prabha says so, she reminds him that she is married. Once, alone in her flat, we see her hugging and embracing a brand new gleaming rice cooker that has arrived through an anonymous parcel. Since the parcel carried a “Germany” stamp, she hopes it is from her distant husband in Germany.

The significance of the lives of these three women is that they are constantly trying to cope with the present state of their lives. Though other than Anu, we hardly see the other two women smiling, we never hear them cribbing about their ‘destiny’ or, building hopes around a bright future on the morrow and this makes it easy for the audience to identify with them. Even to adore them.

The entire scope and horizon of the three women change when they visit the seaside village of Parvati. The visuals, the sounds and the seascape change the mood of the film. We see Parvati walking into the waves of the sea, while Prabha smilingly watches from the shore. Anu keeps busy making love to Shiaz who has also come without the other two knowing. The lovers surprisingly discover some “love” graffiti written in chalk by early lovers on the walls of the cave they are using as their hideout such as “Pappu Loves Shalini” and Shiaz adds his own bit with “Our love is like the endless sea” in Malayalam.

We slowly come to grips with the thought the film brings out. “The word ‘place’, geographically speaking, can be defined as an area or a region which possesses some characteristic in the context of preconceived ideas, local conditions or events. But the term has varied meaning, in its myriad nuances, when it comes to literature, films, music, architecture and photography.”

One however, must assert that the film would not have been what it now is without the solid contributions of the technical crew not to speak of the actors, every single one of them, major and minor including the middle-aged man rescued from drowning, the only episode that hints at a bit of unwanted melodrama in the entire film.

Let us begin with Ranabir Das’ cinematography who practically washes the film with different shades of blue and aquamarine and yet never allows the dominant colour to wash over the non-blue scenes such as the teeming crowds on the streets, the flower market outside Dadar (West) station, the dark interiors of Prabha and Anu’s room, the crowded bus in which Anu and Shiaz are enjoying brushing against each other and the wide expanse of the sea and surf in the village. Topshe’s original soundtrack resounds with sounds of the waves of the sea, dry leaves and twigs crackling under the feet of Anu and Shiaz and sometimes, the softened sounds of the trains’ wheels grinding against the tracks. The music is soft, subdued and low-key suffused with notes from a piano enriching the ambience of the entire film. The editing also smoothly and seamlessly moves from the bustle of the city to the open wideness of the sea and the waves.

For these three women, the pain of migration could have led to feelings of bitterness or regret but both Payal Kapadia and her three characters are never bitter though they have enough cause for cynicism because in one sense, their displacement – from Kerala to Mumbai or, from Mumbai to a seaside village, migration has become their natural flow of life and they flow along with the city and whatever it means for them. Is it a movement from darkness to light? Or, is it the other way round? For that, you must watch the film.

*****

What's Your Reaction?