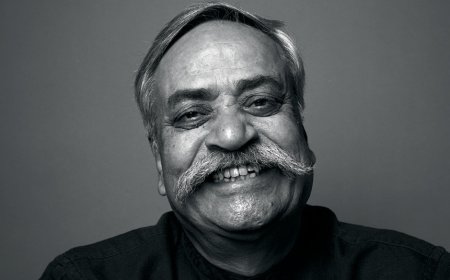

Tribute: ARUN ROY - Creator of a Unique Genre through Contemporary History

Dr. Shoma A. Chatterji pays a tribute to the filmmaker ARUN ROY who made few directorial films with great difficulty for want of a producer as his subjects and his casting were both unique.

Arun Roy, a director with a difference, passed away in Kolkata last week after a prolonged fight with cancer. I call him a “director with a difference” because his career as a director was not only short-lived, but also filled with lesser films than the average, popular Bengali filmmaker. This is not because he passed away at the relatively young age of 56, but also because his films, with a strong social agenda, was also backed by thorough research without losing out on the quality of the few films he made during his lifetime.

The totally unknown Arun Roy, with no links to cinema, stunned everyone with his first directorial film Egaro. A bit slow to pick up at the box office, Egaro caught up with big budget multi-starrers so much that it began to draw crowds everyday. It was exempted from Entertainment Tax by the then-CPM-ruled West Bengal Government, much to the thrill of the new filmmaker.

Asked why he made his entry into a full-fledged feature film so late, only in 2011, Roy said, “I dragged my feet for several years writing scripts and assisting in direction of television soaps and serials like Spandan and Manik with the desire of making a really good film sometime. I wanted to work on an original, powerful script that would translate as entertainment, information and education for the whole family and would stand the test of time. I know all this sounds quite cliché but it is the truth. I watch films everyday and discovered that human relationship is the basic credo of every film that reaches out to every class of audience. This was the basic idea I had in mind.”

Egaro

Roy’s first, full-length feature film Egaro (Eleven) was a celluloid reconstruction of Mohan Bagan’s historic winning of the prestigious IFA Shield from its British opponents, East Yorkshire Regiment on 29th July 1911. The narrative blends fact with fiction to create a parallel theme of an underground revolution going on at the same time in Bengal, and one of the players is a member of this group. In the film, the director brings across the message that Mohan Bagan is not just a football club but a metaphor for an India desperate to drive the British Imperialists back to Great Britain and regain independence.

Egaro is also the first celluloid tribute to the 11 Mohan Bagan players who won the shield, ten of them playing barefoot clad in folded dhotis with just one of them, Sudhir Chatterjee, wearing boots against a team with the right kit, boots, dress, infrastructural support and the typical bias of the White rulers against the coloured Ruled. But Egaro is not just about football. It is about the patriotic passion that drove these eleven players to unite thousands of Indians from the entire Eastern regions who flocked in from Dhaka, Burdwan, Midnapore crossing barriers of caste, class, community and language to watch the players kick and beat up the British teams on the playing field without being punished by the rulers because it was ‘all in the game.’ It is about the killer spirit where the ‘killer’ took prominence not because it was a fight to finish, but because the final match was a battlefield where the winning could speed the movement against Imperial rule and towards freedom. It did, in a manner of speaking. After the historic win on January 29, 1911, the British felt pressurized enough to shift its capital from Calcutta to Delhi on December 12 the same year.

“I was extremely focussed on researching the period and the incidents that led up to the final match. I also went around knocking at the doors of big producers with my script hoping to rope them in. Nothing worked. The big producers wanted me to cast big stars as the main players such as in the roles of Shibdas Bhaduri and Abhilash. I did not want any star, big or small, to impose their star image on my real-life characters. So I waited patiently and continued to persuade new and old producers to finance my film. After a year and a half, a new production house, Magic Hour Entertainment, decided to produce my film and agreed to my terms of not taking stars for my film,” said Roy.

Cholai

His second film Cholai is another example of his commitment. The film retells the real story of how a batch of country liquor sold to rickshaw drivers and poor leather workers in 10 villages in and around Mograhat, and Mandirbazar in South 24-Parganas and Sangrampur in West Bengal beginning from December 14, 2011 killed more than 170 people soon after they drank liquor adulterated with methanol. The liquor, known locally as Cholai, is believed to be produced by a local Muslim 'mafia' and sold to poor labourers in ten local shops for as little as five rupees for a half litre 'pouch'.

Cholai is not just about how the tragedy. It is more importantly about the Rs.2 lakh compensation announced by the State Government to be paid to the family of each victim which did not actually reach them. The real incident involves how a batch of country liquor sold to rickshaw drivers and poor leather workers in 10 villages in and around Mograhat, and Mandirbazar in South 24-Parganas and Sangrampur in West Bengal beginning from December 14 2011 killed more than 170 people soon after they drank liquor adulterated with methanol. The liquor, known locally as Cholai, is believed to be produced by a local Muslim 'mafia' and sold to poor labourers in ten local shops for as little as five rupees for a half litre 'pouch'. For reasons Roy did not wish to explain, Cholai did not have a theatrical release in West Bengal till many years though it is a brilliant political film which describes the nexus between the chain of bootleggers, doctors, agents and so on with a lot of black humor without sentimentalizing the subject.

He did extensive research for seven to eight months travelling through Mograhat, Canning and Laxmikantapur to internalise the lifestyle, the language, the manner of these poor villagers engaged in the business, sometimes along with their wives and grown children. “I lived with some of the families who were distilling spurious liquor, learnt how to make it and also drank cholai to get a grasp over a subject I did not know much about. I learnt the dialect – Dokhno – they converse in and four-letter words and profanity is a part of their everyday language, used by husband, wife and small kids casually and they do not feel these are dirty slangs or abusive profanity. They do not know that this is ‘slang’ because it is a part of their everyday language,” said Roy. He lived with them for three months and drank cholai with them in to blend himself into their ‘mainstream.’

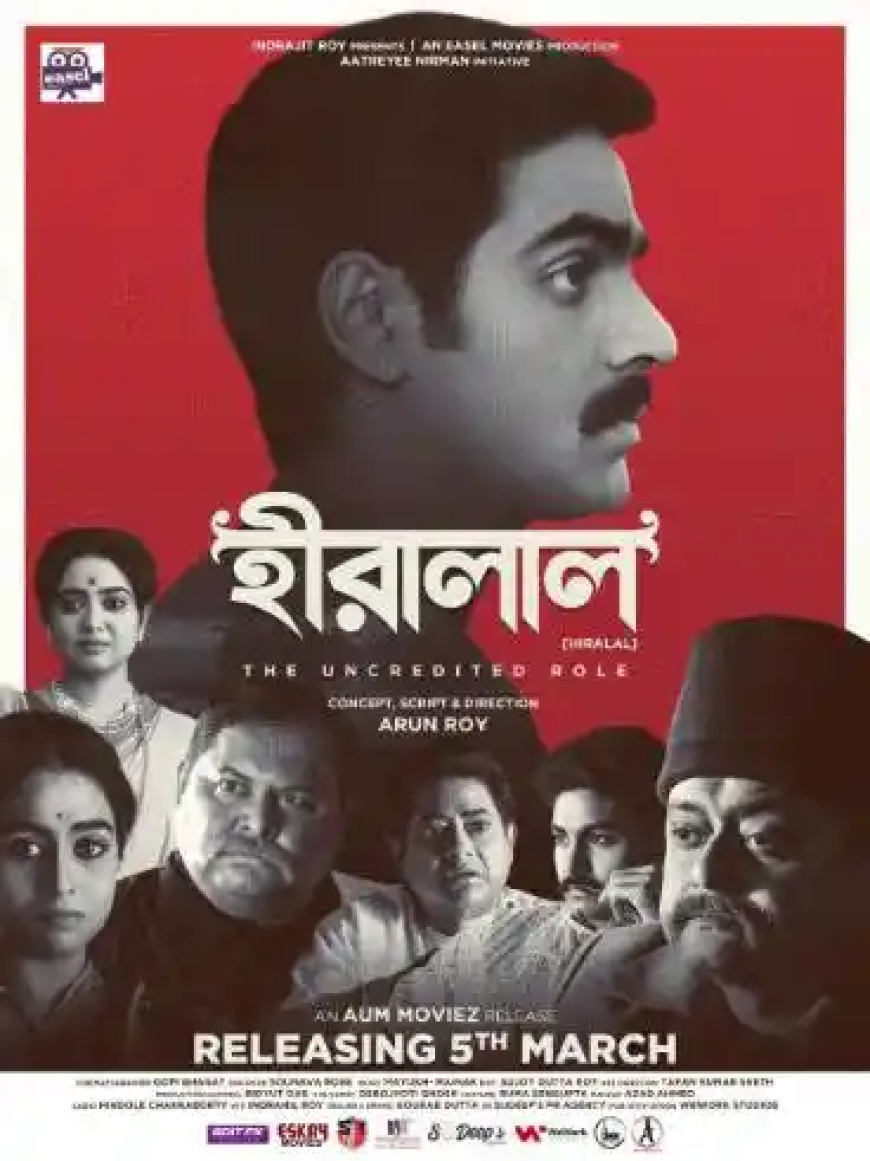

Hiralal

His third film was Hiralal. Hiralal Sen was a noted photographer who became one of the pioneers of filmmaking and film exhibiting in India. The tragic story details the life of Hiralal Sen from the days when he was merely a still photography enthusiast, through his meteoric rise in making films, closing with his subsequent fall from grace. Sen is credited with having made as well as its first political documentary. Yet, scarcely anything is known about the man who is among the pioneers of Indian cinema.

The narrative is divided into several segments that seamlessly weave themselves into one another without jerks and jars. The film appears to have been shot in Black & White but there are splashes of red to show blood and shades of golden yellow and orange to denote fire. Said Roy, “During the time span of the film, life in Bengal, or rather, India, was divided in Black and White and colour came only in the form of blood to depict the inhuman and massive deaths that happened without reason and fire to put fire to everything on the one hand and the fire of funeral pyres on the other.”

The final segment narrating the cross-firing that happens in the different sections of Writers Building takes around 15 to 20 minutes, finally felling the British officers targeted by the three youngsters and they too, either taking in their cyanide pills or placing their guns on their temples.

Roy, who is celebrated for his passion for research without which none of his four films would have been the classics they have become, places the entire credit for his research on researcher Rudrarup Mukherjee, who lives in Howrah and is ready with any historical facts and data anyone asks for within half and hour.

8/12

His next film 8/12 talks about Binay Basu, Badal Gupta and Dinesh Gupta, who on 8th December, 1930 invaded the writers building to kill tyrannical British ruler Simpson and to bring end to the British rule that has tormented India for over 200 years. An important square in Kolkata is called BBD Baug named after these three martyrs. But few today know the full names of “B” “B” and “D” and why the square was named so.

“This is precisely why I decided to name my film 8/12 and not any proper noun. I realised over time that the numbers 9/11 are immediately recognized by every world citizen, almost, and we link it with the twin towers bombardment in the USA. I wanted to bring the date 8/12 to the fore so that no one forgets the sacrifice of these three young Bengali men are carved in the minds of every Bengali and subsequently, every Indian today” Arun Roy lamenting that no one today even remembers the names of Binoy, Badal and Dinesh today which is sad indeed.

‘Operation Freedom’ launched in 1930 rose violently against police repression in different Bengali Jails. In August 1930, the group planned to execute Lowman, the Police Inspector General. Benoy ultimately shot him, at the Medical School Hospital in Dhaka, escaping to Kolkata soon after. We see Netaji raising his voice when imprisoned against the inhuman treatment meted out to political prisoners by cooping 100 captives in a cell that holds only 30.

The three comrades, Benoy, Badal and Dinesh, decided to kill N S Simpson, as well as other Britishers, to strike terror into the heart of the Raj’s official circles. This was to be an attack on the Writer’s Building, the Secretariat, in the heart of Kolkata.

Said Roy, “During the time span of the film, life in Bengal, or rather, India, was divided in Black and White and colour came only in the form of blood to depict the inhuman and massive deaths that happened without reason and fire to put fire to everything on the one hand and the fire of funeral pyres on the other.”

The final segment narrating the cross-firing that happens in the different sections of Writers Building takes around 15 to 20 minutes, finally felling the British officers targeted by the three youngsters and they too, either taking in their cyanide pills or placing their guns on their temples.

The only negative point this critic has to make about the film is its very loud background score that does not give us even a moment of silence. When asked why, Roy said, “This is not a tragedy I made. It is a celebration, a matter of pride for us and there cannot be any celebration without music, can there?”

Bagha Jatin

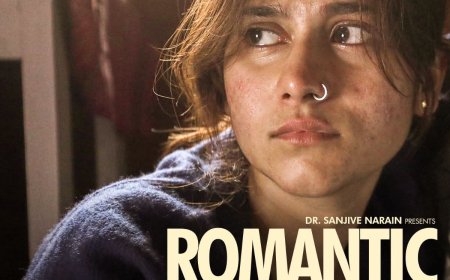

The final feature film that featured his unique genre was Bagha Jatin which automatically acquired a commercial label because the title role of a famous revolutionary of Bengal before the Partition was Dev. Bagha Jatin is a historical Bengali film that brings to life the remarkable story of the Indian independence activist and freedom fighter, Jatindranath Mukherjee, famously known as Bagha Jatin. Directed by Arun Roy and written by Sounava Bose, the film provides a captivating glimpse into one of the key figures of India’s struggle for independence.

Dev’s portrayal of Jatindranath Mukherjee is compelling and serves as the backbone of the film. His performance effectively conveys the courage and determination of Bagha Jatin in his quest for freedom. Sreeja Dutta as Indubala Banerjee, Bagha Jatin’s wife, adds depth to the narrative, and Sudipta Chakraborty as Binodbala, Bagha Jatin’s elder sister, brings emotional weight to the story.

The film successfully immerses the audience in the era of the Indian independence movement, showcasing the sacrifices and dedication of revolutionaries like Kshudiram Bose, Arabindo Ghose, and others. Each character contributes to the tapestry of this historical narrative, making it a comprehensive depiction of the period.

Arun Roy’s direction captures the essence of the time and the challenges faced by those who fought for India’s independence. The cinematography by Gopi Bhagat effectively transports the viewers to the early 20th century, and Nilayan Chatterjee’s music complements the storytelling, evoking the right emotions.

*****

What's Your Reaction?