Trauma, Memory, and the Hushed courage: An analysis of Baharul Islam’s The Seventh String (2021)

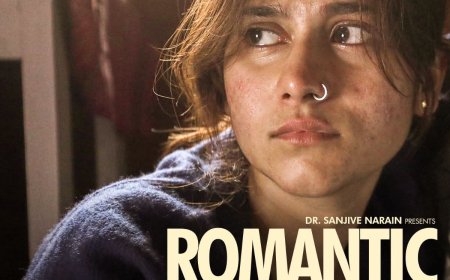

The Seventh String is a quietly poised film in which a life fragmented by the forces of an unchecked phase of depression wreaks havoc on both the physical surroundings and the mental state of its protagonist with deliberate emotional accuracy that ultimately wounds us. The film, at first, has a deceptively simple setup: a young girl, Nishtha Kahyap (Barkha Bahar), returns to her hometown after twelve years and enters a hut that is part of a local folk tradition where people come to share their burdens with other people, burdens too heavy to carry alone. As she unburdens herself, she describes the moment when, at thirteen, her childhood was shattered. What follows is not the heightened drama of confrontation, but something much more muted, more discomforting—the quiet sadness of memory returning, not to accuse, but to comprehend.

Noted Indian actor Baharul Islam, who has donned the hat of a director, clearly understands the material and demonstrates great confidence in it; he does not oversay or underplay. The line between moral certainty and emotional complexity is thin, and this film moves along that line very gracefully. The screenplay knows the difference between revelation and reckoning. For example, the community space where the villagers go in order to be vulnerable with their feelings shows many ways that people cope with trauma and ultimately reiterates that there is no right way to deal with it or consider it as a life-changing event. While the adult world is impacted within a common societal mindset of groupthink, in the community space, the protagonist ends up imagining an unexpected emotional space, which is free from melodrama, and favours colder, deeper and ultimately more human circles. The film’s restraint in tone is a notable achievement. Thus, the hut becomes a personal sanctuary for Nishtha, away from the demands of his family based on expectations created by social norms and the hardline belief that a girl is made to marry young. It seems the hut also becomes a place of abode for the people wrestling with the unimaginable burden of unspeakable weight.

Nishtha is dealing with trauma that she has been bottling for almost a decade, and not just in silence, but a silence epitomised by chronic loneliness and dispiritedness. Carl Jung’s idea of “what you resist persists” suggests that when you suppress an emotion, situation, or part of yourself, it is more likely to linger—or even intensify—over time. This is where Nishtha confronts her Shadow Self: the pain, guilt, and buried rage that have long shaped her inner life. The film recognises that healing begins not with blame, but with the difficult process of acknowledging what has been pushed into darkness. What she is looking for in the company of the villagers gathered together is not justice, not even an apology, but simply a way to rid herself of the burden of a haunting act. The performance by Barkha Bahar is equally precise. She carries the emotional heft of her character's journey through the smallest of gestures—a hesitant glance, a tightening of the jaw, the faintest catch in her throat.

Today, most feature films are saturated in noise. The Seventh String dares to speak in subtle gestures. And like a thoughtful whisper, it lingers. The film portrays the emotional struggles that some girls endure during the fragile years of childhood with honesty. Their pain often goes unnoticed or unaddressed, and it deserves more than just fleeting sympathy. What they truly need is lasting empathy and sustained support—something deeper and enduring, not merely a momentary gesture of concern. Long after the credits roll, the tale of Nishtha stays with us, not because of what it shows, but because of all that it refuses to normalise.

What's Your Reaction?