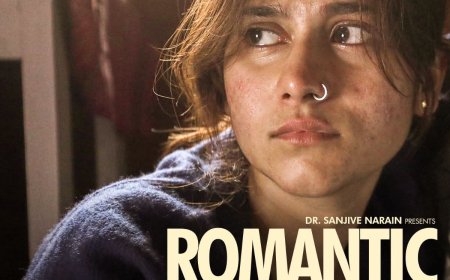

MEELON DUR : A BEAUTIFUL DOCUMENTARY BY MEGHA ACHARYA

Dr. Shoma A. Chatterji provides a detailed interview with Megha Acharya about her 50-minute documentary film, Meelon Dur, which explores the lives of female labourers working in a brick kiln in India.

Megha Acharya is a documentary practitioner, based in New Delhi. She used to work as Senior producer in Chambal Media, home to Khabar Lahariya. Under their banner, she made her first long documentary Miles Away. Her work has dealt with the subjects of climate change, gender, agriculture and public healthcare policies. Her film Sudhamayee (2019), part of her diploma film project in Sri Aurobindo Centre for Arts and Communication, has won best film, best director and special mention in prestigious festivals across India. It was previously streaming on Mubi and is currently streaming on DA films.

She has made a 50-minute documentary film called Meelon Dur which deals with The everyday-lives of three female labourers working in a brick kiln in India takes an upsetting turn after an unexpected rainfall halts their work. What unfolds is a threatening tale of unorganized labour and economic debts in a rapidly urbanizing India. This writer had the good fortune to watch the film through a screener sent to me by Kriti Film Club that screens and shares documentary films on development, environment, and socially relevant issues, in an effort to positively influence mindsets and behaviour towards creating an equitous, just, and peaceful world. Kriti Film Club also helped me in creating a direct contact with the director to facilitiate a one-to-one interview on Meelon Dur which has featured in festival screenings several times.

Why did you decide to call it Meelon Dur?

The film’s title has been largely inspired by the tempo journeys that labourers make to far off places for work. Inter-state migration, intra state migration of labourers is quite common. There are bhojpuri songs that talk about migration to far off places in order to fill the stomach. All these things collectively inspired the title ‘Meelon Door’.

What inspired you to make this very challenging documentary?

The documentary has been produced by Khabar Lahariya, a feminist media network, along with two professors Paula Chakravarty, and Michelle Buckley from NYU and the University of Toronto respectively. Both the professors had reached out to Khabar Lahariya for doing field research for them on a research they were working on. The research was based on labourers migrating to Brick Kilns in the Bundelkhand region. The film’s Associate Director, Geeta, also a senior reporter at Khabar Lahariya, led the research team on ground. After the research, Michelle and Paula wanted a documentary made on this subject. I was associated at the time with Khabar Lahariya, so, the management there, handed me the responsibility to develop the film.

How did you manage the funding for the film?

The film has been made on a tight budget. The professors had given us funds. Khabar Lahariya put in some finances, and other than that, we received a short award money of 3000 pounds (whickers bursary) at a pitching forum called Docedge Kolkata.

The film has been shot entirely on location in some Bundelkhandi space where brick kilns are located. What challenges - physical, climatic, social and political did you have to face during the shooting?

Honestly, filming in such a terrain through and through was a massive challenge. The climate and physical landscape was a big challenge. Every month, the temperatures in Bundelkhand fluctuate. In the months of December, January, the cold is unbearable. And the month of May would invite heat that prohibited our cameras from operating optimally. The change in weather would also change their working hours and timings. In the month of Feb, they would start working at 2 am in the morning. So our filming schedule also had to be planned according to their work schedule. I remember my cinematographer Aditi and I constantly planning the shoot hours for the right light. In terms of social barriers, negotiating with the kiln owner constantly was a little difficult.

How did you manage to convince the migrant people to place their trust in you?

Filming inside a space that is known to exploit labourers is really difficult. But the kiln owner and management understood that the film’s intention is in no way to tarnish the kiln’s reputation, or create problems for them. To be honest, this particular owner was fairly decent and accommodative. Which is why the kiln owner was okay with us being in that space for so long. It took time for the male labourers to open up to us in general. The husbands of the women in that space did not like us getting so pally with their wives. Relationship building amidst the differences in gender, class, and caste takes time. The only way to deal with all our barriers was to be patient and constantly talk to the labourers.

Your main crew is peopled by women. Is there a special reason for this?

Khabar Lahariya is an all women run organisation, so the film’s team had to carry that forward which I am very glad of. If there were men in the team, I don’t think we would have been able to befriend the women, the way we did.

The women in the film are not actors at all. How did you prep them if at all? Or, did you capture them on camera as is?

We formed a genuine friendship with them in the first couple of schedules. Gaura, one of the women was slightly closer to our age. So her and I just talked a lot about everything under the sun – from parents to relationships to clothes, food, everything! Geeta’s presence in me becoming friends with the three women was also crucial as she knows Bundeli, the land of the language. We didn’t prep them. Their comfort with us allowed us to film them as they went about with their everyday life.

Your film begins in November 2021 and ends around June 2022 when the migrant workers are readying themselves to go back to work in the brick kilns. How did you interact with them over the entire period and where did you live?

We would just observe them while they were working. We would have no interactions during that time. They’d be too busy to interact. We would mostly engage with them when they were free or resting. Our third schedule, in the month of January, when it rained, we spoke to them a lot as they had no work. Over time, as we built an organic friendship with them, they would themselves start conversations with us.

The women seem to have found happiness by playing Holi and enjoying themselves within those strenuous circumstances. What is your reaction to it and also the reaction of the crew?

My favourite moment is when Laxmi, a character in the film says that they love spending holi in the kilns as they are independent and free here. Unlike in their parents’ or in-laws’ homes where they would remain within the confines of the concrete. It says so much about the complexities in their life. They experience freedom in a space that has otherwise the tendency of being so exploitative. Also – the entire crew loved holi! We played and danced with them too.

How do you plan to distribute and exhibit the film considering documentaries do not have regular exhibition outlets in our country?

We are currently dependent on festivals, university spaces, and other film club avenues to screening the film in the country. Like you said documentary distribution’s non-existence is a big challenge, and we are currently experiencing that challenge!

How do you define the "independent documentary movement in India" with special reference to women in this field?

The last 2-3 years have been a great time for Indian documentaries, with films like All that breathes reaching prestigious avenues. Indian documentaries have certainly come under a well-deserved spotlight. But I still don’t know if what has happened in the recent times has made things easier for independent documentary filmmakers. Because documentary funding and distribution inside the country is still nothing. Most people are dependent on foreign funding. But the one good thing which I personally have experienced is women film collectives. I am part of one such collective, and have found support whenever needed!

*****

What's Your Reaction?