MIFF 2024: An interview with ‘The First Film’ (2023) filmmaker Piyush Thakur

Dipankar Sarkar provides an interview with ‘The First Film’ (2023) filmmaker Piyush Thakur.

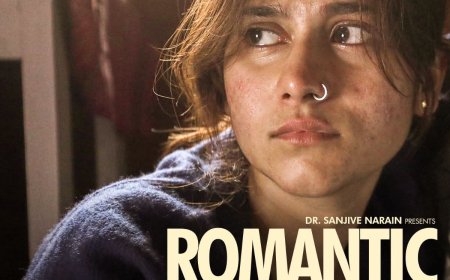

Piyush Thakur’s short film, The First Film, is set in the 1960s. In this period, women from rural India are prohibited from entering the perceived immoral premises of film theatres. In such a conservative society, a teenage girl, motivated by her male companion, decides to break the norm before bidding adieu to her free-spirited life. Shot in black and white, this mesmerizing film showcases assured direction and a meditation on love, memory, and invented history that’s deeply personal.

In this interview, Thakur spoke about why he chose monochormatic visuals, about the contribution of his collaborators and what motivated his stylistic choices.

How did the idea come to you?

The idea for this film originated in 2012. It was at the Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival, where my student short film Khara Karodpati - The Real Millionaire (2011) was scheduled to premiere before an audience of approximately 1,400 people in a grand auditorium. While awaiting the screening, I noticed an elderly French couple, likely in their late 80s, patiently waiting in line to enter the theatre. The wife was in a wheelchair, tenderly attended to by her husband. Their passion for cinema, despite their age and challenges, deeply struck me.

After the screening, to my surprise, the same couple approached me with radiant smiles, offering warm compliments in French. Though I couldn't grasp their words, their affection for cinema and love for each other was unmistakable in their expressions. This encounter profoundly illustrated to me the universal allure of cinephilia, transcending barriers of age, gender, and nationality.

That evening, inspired by this moving experience, I decided to at least write, even if I decide not to direct it, a story centered around cinephiles and the transformative power of cinema itself. I began to curiously ponder: How far would a cinephile go, to watch a special film?

Why did you decide to set the film in 1960?

The decision to set the film in the 1960s was influenced by the rich cinematic heritage of that era, often referred to as the 'Golden Age' of Indian Cinema. During my time at Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), I had the privilege of watching many of these classics on 35mm prints at FTII and The National Film Archive of India (NFAI). I particularly love the works of V. Shantaram, Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt, and Vijay Anand. The music of this era also holds a special place, rich with melodies that deserve their discussion.

Moreover, my grandparents, massive movie buffs themselves, used to tell us stories of how watching a film back then was a grand event, often involving journeys across the city. This nostalgic backdrop, coupled with my encounter with the elderly French couple at Clermont-Ferrand, sparked the initial idea for the film. Upon returning from France, we began drafting the screenplay in February 2012. Over the decade, the narrative evolved, transitioning from portraying an elderly character to reimagining them as a younger self in the vibrant background of 1960s India.

Did your collaboration with Deepak Lohana help you develop the screenplay?

Deepak is my high school friend. When I was making Khara Karodpati - The Real Millionaire his insights were invaluable, leading him to co-write that film.

Our collaboration, rooted in a shared love for cinema but differing worldviews, added layers of depth to the screenplay of The First Film. Over the years, we explored various narrative arcs and character dynamics—from husband-wife relationships to sibling dynamics—before settling on the final version. Throughout this journey, the core emotion of the film remained constant, though the narrative underwent significant evolution. Remarkably, the last scene from our original 2012 draft remained unchanged in the final script.

Given that our characters were film buffs from an era unfamiliar to us, we immersed ourselves in the psyche, behaviour, and ambience of that time by watching numerous movies. We focused on popular Hindi films released from January 1950 to the 1960s, the period in which our film is set. This approach was invaluable; understanding film enthusiasts from different eras requires inhabiting their experiences. We watched every important and hit films and engaged in extensive discussions, viewing them as an audience rather than scriptwriters. We spent more than three months doing only this, and honestly, it was the most enjoyable part of the process. We discovered many cinematic gems during this period.

Our script development occurred over late-night phone calls, and we didn't meet in person to write this script until the shoot day. Deepak's bond with his cinephile grandmother (Nani), who inspired the protagonist's name 'Devi' added a personal touch to our story.

Writing this script was a continuous process that extended into the editing phase, with significant narrative changes happening during post-production. The final film reflects an organic evolution, making it hard to distinguish between what was written initially and what emerged during editing.

Why did you begin the film with a prelude?

I have a strong fascination with the three-act structure and often find myself drawn to writing within that framework. However, short films present the unique challenge of condensing a beginning, middle, and end within limited time constraints. So, we draft a feature-length script, often over 120 minutes, and then work to distill the same story and emotions into under 30 minutes. Though this process is time-consuming and difficult, it allows for creative freedom before trimming it down.

Originally, the film wasn't supposed to begin with a prelude. We even wrote and shot it differently. After making the first cut edit, I lost perspective on the film, feeling too attached to the material to view it objectively. That’s when my friend and FTII batchmate, Anadi Athaley, a brilliant editor, stepped in to help. He replaced our original opening with the prelude, a decision that fundamentally altered our narrative approach and injected new life into the film.

Whenever Devi speaks to Mohan, she is usually observed behind the window bars, except in one instance. Even towards the climax, they are separated by a collapsible gate. Why is it so?

That's a keen observation. This was a deliberate choice to reflect Devi's character and convey her sense of entrapment. Devi holds a secret dream, but her surroundings constrain these aspirations. By depicting her behind window bars and separated by a gate, we symbolise the restrictions and inner demons she confronts.

You have directed and edited the film. How did it help you shape the final product and achieve your vision for the story?

The journey of creating this film spanned several years, navigating through significant challenges. We wrote the first draft in 2012, shot it in 2018, and are now screening it in 2024.

Our film features multiple locations and numerous characters. When my co-producer and FTII batchmate, Anadi, read the script, we began strategizing on how to manage this production with short film resources. I was fortunate that Anadi, his family, and IPTA Raigarh supported us. After a location recce, we decided to shoot in Raigarh and places around in Chhattisgarh. The schedule was long and exhausting, even disrupted by a cyclone and extremely cold weather during night shoots. The film’s protagonists, Devi, played by Priyanka Beriya, and Mohan, played by Vasudev Nishad, were facing the camera for the first time and so was most of the cast in the film. We conducted workshops for weeks to help them get comfortable and embody their characters.

My initial aim was to make Priyanka and Vasudev comfortable with the filming process and develop a friendly rapport with them. To help them feel at ease, we kept the camera rolling like a documentary, capturing moments when they were not camera-shy or nervous. This approach resulted in over a hundred hours of footage, which we had to edit down to a short film. The first cut was over 70 minutes long. Through continuous editing and feedback, we gained a fresh perspective that faded after the shooting.

While I typically advise against self-editing, especially when the director is also the writer, I found myself in that role once again. Visualising the script through shots and cuts is where I find the essence of storytelling that resonates with me. Editing this film allowed me to meticulously design each sequence, ensuring every shot served its purpose. During challenging moments on set, whether due to limited permissions or time constraints, I could swiftly adjust the rough edit, optimising our opportunities available at that moment. The film itself was an experiment, encompassing elements of silent cinema, drama, melodrama, and even a musical sequence all in a 24-minute duration.

In essence, every minute of our film was an exploration, and editing it myself felt like the natural culmination of this process.

What inspired your decision to shoot the film in black and white?

The decision to shoot in black and white was rooted in our early stages of script development. Our primary aim was to capture the period look of the era depicted in the story. Initially, we contemplated using a 4:3 aspect ratio reminiscent of 1950s Indian cinema but opted for 1.66:1 due to the screen feeling overcrowded with the style of the subtitles we were experimenting with.

Additionally, the choice resonated with our protagonist, Devi, whose life unfolds in monochrome, where cinema serves as her sole escape and source of colour. Black and white cinematography enabled us to underscore this facet of her character.

I was particularly inspired by the old popular Hindi films, which had a black and white look that was neither overly contrasty nor perfectly lit. While we could have manipulated the image in post-production to achieve various effects, I wanted a bright and lively black and white aesthetic, rather than a serious or high-contrast one. This made the film feel more earthy and raw, contrasting with the polished digital black and white commonly used today.

During the Digital Intermediate (DI) process, we experimented with different visual looks to enhance the film's appeal. However, these adjustments often distracted from the story, which I wanted to avoid. The bright, raw aesthetic we aimed for is similar to that of black and white era Indian films.

My cinematographer and FTII batchmate, Sonu, and I had extensive discussions and conducted various tests before finalising this look. Shooting in black and white requires meticulous planning in terms of production design and costumes too, as certain colours can appear differently on screen.

Many advised against making a black and white film, as film festivals and distributors often shy away from them globally. However, this visual approach was essential for our story, and since I was producing it, I went ahead with it.

What was your brief to Pranil Desai for composing the background score?

Music plays a pivotal role in this film, and I wanted Indian Classical Music to reflect the deeply rooted Indian story and emotions. I consulted several ustads and senior classical musicians who appreciated the rough cut and were keen to collaborate. I aimed at a meticulous approach, composing music tailored to each scene. This process would involve iterative adjustments to ensure perfect harmony, demanding considerable time, patience, and a spirit of experimentation.

Pranil Desai, a talented young musician with a background in Western music, was recommended to me by a mutual friend. This is his debut film. Despite his initial unfamiliarity with film composition, his enthusiasm and openness to explore and learn impressed me. Choosing to collaborate, we embarked on a two-year journey where both of us delved deep into the nuances of Classical Indian Music.

We had in-depth discussions about the primary string instrument to use, initially recording a demo with the sitar too. However, I felt the sarod better suited the film’s playful nature and wanted to avoid the strong nostalgic connotations of the sitar associated with ‘Pather Panchali’.

Our collaboration transcended a simple brief. It involved Pranil composing and me integrating the music into the edit. We worked tirelessly through the COVID lockdown, recording instruments like the tabla, sarod, and violin/viola live online from young talented musicians like Tanay Rege, Roopak Korgaonkar, and Anirban Bhattacharjee. These online recordings were then mixed by Pranil and then I would edit and send him back notes to change to suit the film's drama and he would re-do it. When the pandemic subsided, our Sound Mix Engineer Pradyumna Chaware suggested re-recording the music in a studio for optimal theatre sound quality since music was recorded online. With a very heavy heart, we once again re-recorded everything from scratch. This exercise paid off, as the music became a crucial element of the film.

The film has been nominated for various film festivals around the world. How have these participations helped you?

I am grateful that our film has been selected for numerous prestigious film festivals worldwide. It had its world premiere at Bogoshorts in Colombia, which is an Oscar-qualifying festival. Notably, it was the sole Indian entry in the competition. Additionally, the film was featured as 'Market Picks' at Clermont-Ferrand and was selected for 'Film Bazaar Recommends' at MIFF Doc Film Bazaar. Its Asia premiere took place in the National Competition at Mumbai International Film Festival (MIFF).

Screening our film in theatres has always been a priority for us, particularly in today's digital era dominated by OTT platforms. It's truly gratifying that a film celebrating the cinematic experience has the opportunity to be showcased in theatres.

Participating in these festivals has provided invaluable opportunities for us. It allows us to receive diverse feedback from international audiences, including those viewing the film with subtitles in Spanish, French, and English, in addition to our primary audience in India.

Moreover, festivals such as Clermont-Ferrand, Bogoshorts, and MIFF not only showcase films but also host markets that facilitate short film distribution. In Asia, particularly in India, short films often serve as a stepping stone to feature films with a limited market. However, European festivals and markets offer tremendous exposure, recognizing short films as a distinct and valuable art form in their own right.

What are your future projects?

Currently, we're actively developing new stories. One significant project from 2017 is 'Your Big Indian Sumo', an Indo-Japanese coming-of-age feature film. This script is influenced by my deep love for Japan, and it was also shortlisted for the Sundance Screenwriters Lab that year. While we were slated for production back then, our focus shifted to 'The First Film'. We may revisit this project in the future or explore entirely new ideas. I have several concepts in mind and will soon determine the best approach - long or short format, to bring these stories to fruition.

*****

What's Your Reaction?