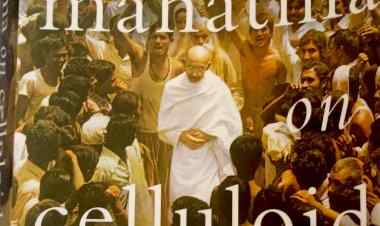

Tagore's impact on Cinema

Dr. Shoma A. Chatterji provides a tribute to Rabindranath Tagore on his death anniversary.

Rabindranath Tagore’s Natir Pooja’s dramatised version was first staged at the Jorsanko Thakurbari in Kolkata in 1927. It was again staged at the New Empire, Kolkata in celebration of the poet’s 70th birthday. An impressed B.N. Sircar, founder-proprietor of New Theatres, invited Tagore to direct a film version under the New Theatres banner. The New Theatres Studio played host to Tagore in 1931. The studio was flooded with crowds assembled to have a glimpse of the great poet. Tagore directed the film, shot on NT Studio’s Floor Number One. He also played a role and assembled his acting cast from Santi Niketan. Nitin Bose cinematographed the film and Subodh Mitra edited it. The film was shot within four days. Breaking the conventional rules of cinema, Natir Pooja was filmed like a stage play. The story was inspired by a tale from the Buddhist series in Abadan Shatak. After editing, the footage was 10,577 feet. It was released at Chitra Talkies on 14th March 1932. Sadly, the prints of the film were reportedly destroyed in a fire at the New Theatres.

In a country like India, with a high rate of illiteracy and a diversity of languages, cinema has evolved into a major medium of communication to reach Tagore to the masses. The process works backwards in India or even other English-speaking countries where sub-titled films based on or adapted from a Tagore original could inspire viewers to read the literary original after having watched the film. A case in point is the international release of Ghosh’s Chokher Bali. When an Indian publishing house brought out a paperback English translation of the novel almost simultaneously with the release of the film, the book sold out like hot cakes in Indian metros. Interestingly however, the film failed to repeat the magic the paperback did.

A film based on, adapted from, interpreted from Tagore’s novel or short story or poem offers infinite scope for argument, discussion, analysis, debate and questions among audience, critics and scholars across the world. An illustration of this is the massive volume of scholarly treatises that have and are still coming out on Satyajit Ray’s Charulata, based on Tagore’s novelette, Nastaneer. This has led to the creation of a completely new genre of writing on cinema – writing created from and by cinema centred exclusively on films based on Tagore’s works. The debate on Ray’s films based on Tagore’s works goes on till this day. Ray’s Charulata (1964) is based on Nastaneer (The Broken Nest) a novelette of around 80 pages, written by Tagore in 1901. Its translator, Mary M. Lago, describes it as “one of Tagore’s best works of fiction.”

Other than the Apu Trilogy, Charulata, perhaps, is the most hotly debated, variedly interpreted, widely discussed and critically questioned among Satyajit Ray’s films. They continue to shed new light on the film. Most of these debates are around the question of Ray’s fidelity to the Tagore original, since Tagore and his works still remain too sacro sanct to be subjected to a filmmaker’s interpretations. Ray personally responded to attacks on his alleged distortion of the Tagore original Nastaneer through his article Charulata Prasange in the collection of articles, (Bengali) Bishay Chalachitra. They were addressed in the form of letters directed at Ashok Rudra, who attacked Ray for the diversions he made from the original in Charulata. Ray’s final article was “a wonderful piece of literary criticism of the Tagore original in the then-distinguished Bengali little magazine Parichay in 1964.”

A massive volume of scholarly treatises have and are still coming out on Satyajit Ray’s Charulata, based on Tagore’s novelette, Nastaneer. This has led to the creation of a completely new genre of writing on cinema – writing created from and by cinema centred exclusively on films based on Tagore’s works. The debate on Ray’s films based on Tagore’s works goes on till this day. Ray’s Charulata (1964) is based on Nastaneer (The Broken Nest) a novelette of around 80 pages, written by Tagore in 1901. Its translator, Mary M. Lago, describes it as “one of Tagore’s best works of fiction.”

Chaturanga (1914), meaning ‘quartet’, also suggests the game of ‘chess’ in Bengali. The novel is a point-of-view, diary-like, first-person narration by Sribilash, a self-effacing scholar. Sriibilash tries to take as unbiased a look as he can, at the lives of his close friend Sachish, the latter’s uncle Jagmohan, the widow Damini, and his own life through the mutations and transitions they go through their interactions in the journey of life.

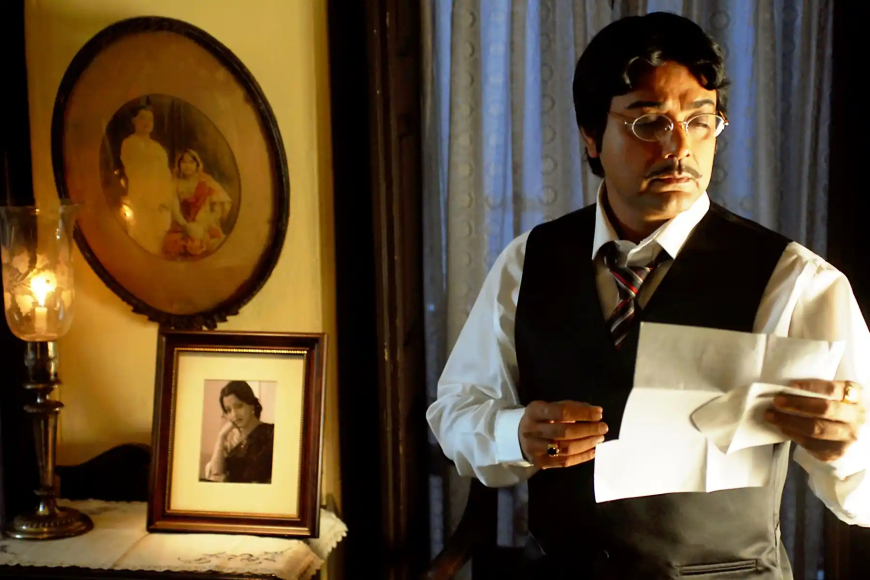

Suman Mukherjee, who made a film version of Chaturanga (2008) took some liberties through structural changes for the change in the language/medium from word to picture. He replaced Sribilash’s omnipresent voiceover keeping the four segments of the novel as they are. He effectively incorporated significant visual, musical and religious metaphors to invest the form and the narrative with Tagore’s world-view as presented in and through the novel in a more concrete and credible manner. This world-view spans multiple layers of meaning. These could be seen in terms of relationships, man’s spiritual beliefs, man’s constant search for an anchor – spiritual, ideological, moral, emotional, the shifting nature of man’s one-to-one communication with God, the conflict between idea and truth, the conflict between physical desire and emotional longing, the blurring of lines between birth and death and last but never the least, society’s moral injustice towards women, cutting across class, religious beliefs, education and awareness.

Mussalmanir Golpo (2010) directed by Pronob Chowdhury, is a film of missed opportunities – in terms of the screenplay that is slow, dragging and loosely strung, weakened further by too many needless flashbacks; the sob-story of Habir Khan’s Hindu mother is superfluous, perhaps offering a slot to the actress who plays it; the dialogue – too full of bombastic oratory juxtaposed against sob-story melodrama; in terms of the cinematography and the editing and finally, it terms of its lovely and melodious musical score where there are several songs too many that never seem to end and that burst into the frame every other five minutes. The next to take the beating is the cinematography marred by wrong, theatre-like shot compositions in medium-shots and the visuals blurring away when the camera tracks back to take a long shot. The editing takes a beating for using the ‘full moon night’ as a bridging device – too hackneyed a strategy to bear fruit. The story has provided fodder for a couple of telefilms earlier but without much success in terms of viewership rating points. The film fails to live up to the promise of placing a Tagore creation on film. It comes out like Tagore packaged in a slightly different masala wrapper.

Noukadubi (Boatwreck) is the most cinema-friendly story by Rabindranath Tagore. It has elements of mainstream Indian cinema filled with dramatic coincidences, love triangles, an accident, even a villain. The story has been placed on celluloid several times including twice in Hindi – Milan (1946) directed by Nitin Bose with Dilip Kumar and Ghunghat (1960) directed by Ramanand Sagar with Bina Rai. Bengali versions came out in 1932, 1947 and 1979. Rituparno Ghosh’s screenplay is different. Noukadubi is about a boat wreck on a night of storm, rain and thunder that throws the lives of the four main characters out of gear, metamorphosing the relationships into something radically different from what the original plans were. Ghosh brings this 1903 story forward to the 1920s. The credits say that the film is ‘inspired’ by the Tagore novel because Ghosh has taken the skeleton of the original story and woven it with his own inputs – cerebral and emotional. He places the story as if written by someone else because Tagore, through his songs, music and photographic portrait as a young man makes his powerful presence felt through the film.

Is Elar Char Adhyay, a celluloid adaptation by Bappaditya Bandopadhyay of Tagore’s point-of-view novel Char Adhyay a political film? Or is it a love story? Many of Tagore’s critics were angered by Tagore’s exposing of ‘patriotism’ preached by Indranath. So Tagore called Char Adhay a love story. The film explores both layers – the intense love between Ela and Atin that draws Atin into the movement because Ela is already in it; and the political angle as seen from different perspectives – the tea-corner owner, the tea shop actually a façade for hiding arms; Botu, whose attraction for Ela is rejected making him angry enough to betray the movement by conniving with the police to capture Atin from his hide-out; Indranath whose sense of ‘patriotism’ like Sandip’s in Ghare Baire is warped. He smokes expensive cigars and travels in lavish cars leaving his followers to indulge in cold-blooded violence, looting and feasting off the loot in the name of ‘patriotism.’ He rules out love between members of the group but does not take steps against Ela even when he knows that she is madly in love with Atin. For Atin, his rule changes, forcing the former to go into hiding.

The dungeon-like darkness in the interiors of the mansion, Ela walking beside a brick wall with Atin looking at her from behind, the contrast in the décor between Ela’s parental home and her Westernised uncle’s ‘modern’ home, the party scene that ends just when it should, Ela standing in front of a window frame, are pictures in a pure blend of serenity and aesthetic beauty that transcends the visual to step into the emotional, the cerebral and the philosophical.

The musical score by Gaurav Chatterjee takes care to reflect Tagore’s secular approach towards religion. There are three Tagore songs, one Baul-like number talking of Muslim philosophy and one English song belted in a party scene but which sounds like a Church song. Gautam Basu’s art direction invests the film with a very realistic ‘period’ texture that reaches beyond its physical reality to reflect the decadence of the movement. The straw structure of the Durga idol lying forgotten and forlorn in the courtyard of the mansion is a beautiful visual metaphor that speaks through its silence.

Through cinema, the director-as-author presents an interesting fusion of the modern and the post-modern thereby raising questions on the possibility of creating a third genre of films based on classical literature in general and on Tagore in particular, a genre that effectively blends the word with the picture, and yet sustains the independence of the original literary work, as well as the independence of the film which then is deeply ensconced within an identity of its own.

*****

What's Your Reaction?