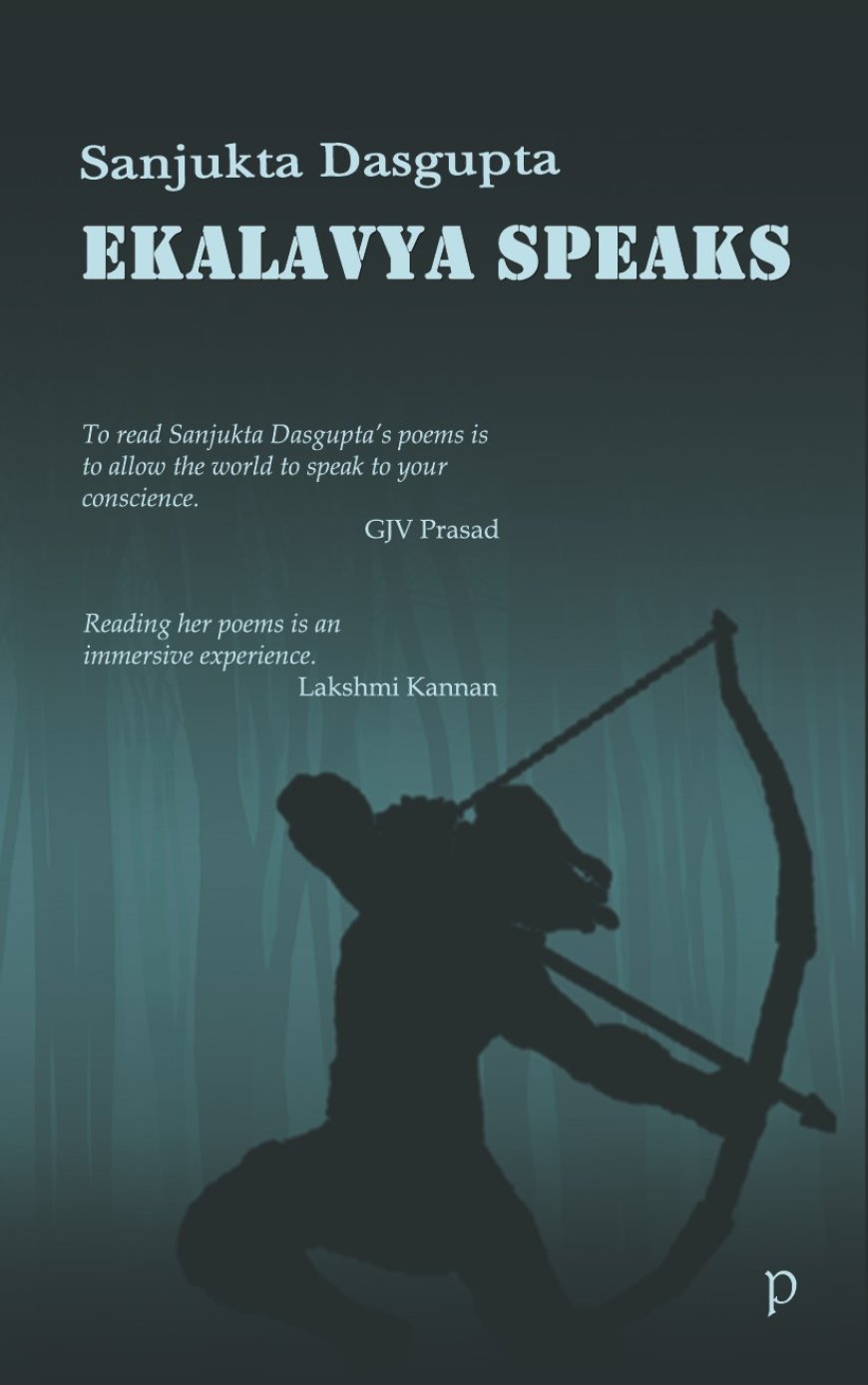

Sanjukta Dasgupta talks about her new book of poetry Ekalavya Speaks

Dr. Shoma A. Chatterji provides an interview with "SANJUKTA DASGUPTA" on her brilliant book of poetry entitled "EKALAVYA SPEAKS".

Meet Sanjukta Dasgupta. She is an academic scholar-turned-poet whose exuberance and energy is incredible for a retired professor of English Literature at the Calcutta University for decades. Her very presence makes you feel that the earth is turning circles and bubbles and everything else so bubbling with enthu is her personality. But she wears her rising fame as a poet of great substance takes a backseat to her totally unassuming persona. In a rather long one-to-one, she opens out on her poetry with special focus on her latest book Ekalavya Speaks published by Pen Prints, Kolkata, with excellent production values topped by a brilliantly telling cover. Over to Sanjukta.

Why the title Ekalavya Speaks?

So long in the biography of Ekalavya as scripted in The Mahabharata, there is no evidence of Ekalavya claiming agency, interrogating the state apparatus, resisting and rebelling through vocalizing his protest. In my poem I tried to re-invent Ekalavya by investing him with a fearless voice of determination. So if the Mahabharata iconized the image of Ekalavya Obeys, in the 21st century, I reconstructed Ekalavya, as we would like to see him in the 21st century. In our times, Ekalavya is not tongue-tied. He speaks and speaks his mind.

You now have around 9 books of poetry. Which genre fulfils you the most - poetry, translation, fiction, non-fiction and why?

Writing poetry and short stories have both been very fulfilling for me. Both these genres permit absolute creative freedom. The element of fidelity to the original text makes translation a more meticulous endeavour, translation is a fusion of art and craft. The rebirth of the original text say from Bangla into English involves immense labour pain but the result can be rewarding intellectually. If non-fiction implies critical writing, then this is entirely a different discipline as the engagement entails wide scholarship, academic and social awareness and an ability to deconstruct received knowledge.

Some of your earlier books of poetry dwelt on the gender question drawing from Hindu mythological characters. What inspired the switch to Ekalavya?

After the publication of my strongly feminist volumes of poetry- LakshmiUnbound, Sita’s Sisters and Indomitable Draupadi, I felt my approach was becoming exclusionary. I felt I needed to address not just women victimized by patriarchal control, but the abjectness of men oppressed by caste and class discrimination. Our dominant Indian epics The Ramayana and The Mahabharata script caste hierarchy that internalizes class structures. As I was writing my poem based on Rabindranath Tagore’s Chandalika, the untouchable Shudra girl, I suddenly thought of the Shudra prince Ekalavya, a victim of caste superiority. But Ekalavya in the Mahabharata accepted his fate, as God ordained. The weaponization of caste did not instigate him into rebellion. I felt I needed to re-invent Ekalavya’s role in the 21st century ecosystem.

You have taken Ekalavya as your starting point and then allowed your mind to travel through time, space and ideas? Does this happen organically or is it well thought out and designed? Elaborate please.

My 9th volume of poems Ekalavya Speaks is about the position of the subaltern in 21st century India and Otherization. Therefore, along with Ekalavya I have tried to raise awareness about many stellar characters in the epics, who have been at the receiving end of mainstream oppression and exploitation. So in this volume I have tried to deconstruct the identities of Karna, Shambuka and Shikhandi from contemporary perspectives. Along with them I have introduced the Santhal rebellion and the leader Birsa Munda. I have critiqued the brutal treatment of Chuni Kotal, the tribal girl who had aspired to obtain higher education and thereby liberate herself from the stigma of being regarded as a member of the marginalized minority community, branded as congenitally inferior to mainstream communities.

How are you reacting to the wonderful response to Ekalavya Speaks from the readers?

I am very pleased with the reader response. Initially, I was a bit apprehensive as I have often been branded as a feminist poet. But I did want to address the politics of intersectionality and focus on diversity and inclusiveness. My readers have understood that my book Ekalavya Speaks, is not a telling or re-telling of Ekalavya’s biography. His biography has many spectacular moments of encounters and that he was ultimately being killed by Krishna. My focus has been the social conditioning of Ekalavya who voluntarily and instantly gave up his right thumb, absolutely crucial for archery skills, just because the wily Dronacharya, asked for his thumb, in order to save his job, as instructor of the Pandava princes. It is this clever strategy of the elite to benumb and hypnotise the minorities into submission that I tried to underscore.

Your writing in most genres is directly and indirectly linked to socio-political issues that dog contemporary society. How does this happen?

As you know, writers through the centuries have tried to expose the anomalies of an unjust world. I have merely followed that tradition in my own humble way. The British poet Shelley had described poets as the unacknowledged legislators of the world. Rabindranath Tagore, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Ezra Pound, W B Yeats, Sunil Gangopadhyay, Sankha Ghosh, Mahasweta Devi, Nabaneeta Dev Sen, can all be described as literary activists. In fact, even a romantic poem is a political poem, after all the personal is the political. No meaningful creative writing can exist in a void.

Please pick 5 of your favourite poems from the book and tell us why you pick them over others?

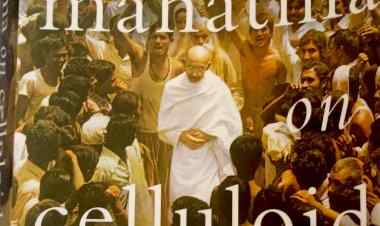

This question is similar to the one which most of us have answered during school and university examinations. To choose five favourites from 86 is a tough call. I would like to foreground apart from the myth-based poems Ekalavya Speaks, Shambuka, Karna and Shikhandi, I would like to mention the poem ‘Bapu’ which was so difficult to write, the little girl desperately crying out to the Mahatma to save her from the predators. The poem ‘Reluctant Voter’ underscores the attitudinal shift of voters, the privileged class vote if they feel like, the disadvantaged class are forced to vote. The third poem is The Coffee Shop where political leaders who had been murdered and martyred meet, from Jesus and Gandhi to Che and Lennon. The 4th poem is Manipur. It has created a collective internal haemorrhage for thinking individuals. The 5th poem is ‘In the Holy Land’ that addresses the ruthless genocide that is still going on in Gaza, aided by weapons supplied by the Global North.

Inspirations and motivations for writing?

I have been writing for several decades now. So I can’t name any particular source of inspiration or a motivating factor. But I have a lover’s quarrel with the world, as Robert Frost had once said. So I have to express in words, as and when my consciousness is roused by a certain decision or act, that diminishes humankind.

Your personal take on Tagore, your spiritual guru, mentor, everything?

Well, Tagore has been a friend, philosopher and guide lifelong. I am still immersed in the social, political and philosophic discourse that emanates from Tagore’s writing in multiple literary genres, such as poetry, short stories, novels, essays, songs, farce, dance drama among others. Tagore was the invisible yet ever present family member during my childhood and young adulthood. My parents hero-worshipped and I did not differ.

*****

What's Your Reaction?