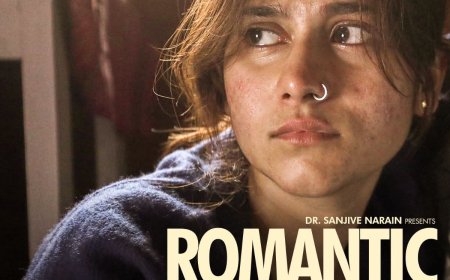

Interview: Vishwas K

Dipankar Sarkar provides an insightful interview with filmmaker Vishwas K, discussing his journey to filmmaking, his personal storytelling approach, and the success of his short film 'Waterman' at IDSFFK 2024.

Vishwas K's short film Waterman is told from the perspective of of young boy Kitty, who lives with his mother in a slum, where there is scarcity of water. As he discovers that he has a power to make taps run water, he decides to use it for helping his mother. The filmmaker captures the activities of the protagonist in an observational manner befitting the unhurried pace of the environment through a rigorous formal approach.

Waterman won the award for Best Short Film at International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala 2024.

In this interview, Vishwas discuss about how he became a filmmaker, his drive for personal stories and his approach to the narrative.

Why did you decide to study at FTII?

Looking back, there were many reasons that led me there. For most of my life, I only watched popular, commercial films—mainly Kannada, Telugu, and some Malayalam and Tamil ones I could get my hands on. I didn’t start watching Hindi or Hollywood films until I got into engineering, where free Wi-Fi made it easier to download them. Seven/Eight years ago, there wasn’t an abundance of content like we have today, so I had to constantly search for films to satisfy my urge of cinema. Then I stumbled upon films which were not popular but had acclaim. These films were quite different from the mainstream. This was my introduction to parallel cinema, and I was surprised to find filmmakers like Kasaravalli and Karnad who had been there all along but I never noticed. I think the reason was that I grew up in a circle where there were no discussions about these kinds of films or filmmakers, so I was never exposed to them. Thanks to the internet, that changed for me.

Also from a young age I always wanted to be a filmmaker. So I met a couple filmmakers in Bangalore asking them to take me as an assistant. But they told me that filmmaking isn’t something you’re taught in a traditional way, but something you learn by observing. But also they insisted that I finish my education first.

It all started when I was watching Kahaani and was blown away by Nawazuddin Siddiqui's performance. That led me to seek out more of his work, and I stumbled upon Gangs of Wasseypur, which introduced me to Anurag Kashyap’s films. I was so fascinated that I started watching his interviews on YouTube. In one of the videos, which had his face on the thumbnail, I clicked on it—it was called FTII at 50. The video featured filmmakers like Jhanu Barua, Saeed Mirza, Ketan Mehta, Jabeen Merchant and others, who spoke about FTII with so much passion and love. This intrigued me, and that’s how I discovered that a place like FTII exists. Until then, I had believed filmmaking was something you could only learn by observing, but this changed my perspective. I became curious. I watched a lot of YouTube videos, interviews with students, and news clips—I think it was after the strike period. What really stood out to me was the political awareness these students had. It was surprising because I hadn’t thought political understanding was important for filmmaking, but their perspectives made me reflect on my own lack of awareness. It was refreshing to see a place that nurtured such critical thinking and allowed students to express themselves.

As I dug deeper, I learned more about FTII’s legacy and its role in shaping Indian cinema. The more I researched, the more fascinated I became by the institute and its history. I’ve always been drawn to places with a strong sense of community and history, so this really resonated with me.

I gave the entrance exam once but didn’t get through. However, the institute had become such a significant place in my mind that I couldn’t give up. On my second attempt, I got in.

The film begins with a game of tossing the coin between Kitty and his friend. What were you trying to convey with this scene?

Honestly, I didn’t think too much before writing that scene—it just came naturally. My main goal was to establish the kid as imaginative and deeply interested in play. Now that you mention it, I realize it also reflected the kind of neighbourhood I grew up in. Things like gambling were a part of life; kids used to play toss with money. Everything becomes interesting with a bit of competition. This is particularly true with siblings—whenever there’s something special at home, like a treat, there’s always this unspoken rivalry over how much you can get. It’s something that only exists between people who are close. So, I think subconsciously, I was trying to establish that kind of relationship between the kid and his friend.

Why did you choose to have Kitty's father stay away from the family?

There were multiple reasons behind it. First, how many kids truly get attention from both parents? An absentee father is quite common, especially in communities where people engage in daily labour or have jobs that require travel. It’s often the mother who stays home, taking care of the children while the father goes out to earn money. That was one reason.

Another was my interest in how children’s realities are shaped, which is deeply influenced by the relationships they have with their family and loved ones. It made sense to me at the time to portray the father as absent, allowing the child to develop a closer bond with his mother. This absence also creates room for a character like the Dastu (Who buys stilts for the protagonist kid) to take on a kind of big-brother role, filling the gap. So, those were the reasons behind that choice—both thematically and for the sake of dramatics.

Whenever Kitty walks on foot stilts there is an overflow of water. What is the significance of water in the film?

I constructed the film from the child’s perspective, and I believe the overflow of water, at least to him, symbolised a resolution to their struggles—particularly his mother’s. It reflects his ability, or perhaps his dream, of overcoming challenges and envisioning a life without hardship. In this sense, water represents the child’s dreams and hopes for a better life.

How important is winning an award at IDSFFK to you?

IDSFFK was the first film festival I attended where I presented my own film, so I was naturally excited. I didn’t expect to win, but looking back at my journey at FTII, it was challenging in the beginning to convey my ideas—whether through words or images. It took time to learn how to express what I wanted to say, and the reception wasn’t always positive. This is something my entire team has experienced.

FTII is known for a certain kind of filmmaking, and there's this unspoken pressure to follow that path. But for me, the drive to make films came from wanting to tell personal stories—ones I grew up with or saw around me, stories that I felt were missing in the films I’d seen. Finding the confidence to express these stories through a film form that felt apt took time.

Recently, some of us at FTII, like Ranjan (Director: Champaran Mutton), have been trying to break away and discover our own styles of storytelling. Winning at IDSFFK has been a huge boost of confidence—not just for me, but for the whole team. It’s an encouragement for all of us to continue making films that reflect our own stories, without feeling constrained by any particular style or tradition.

*****

What's Your Reaction?