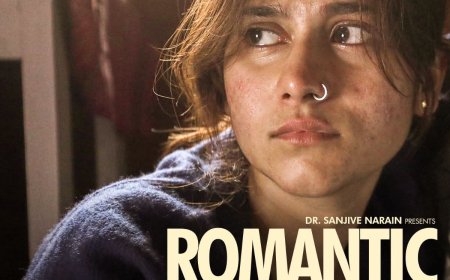

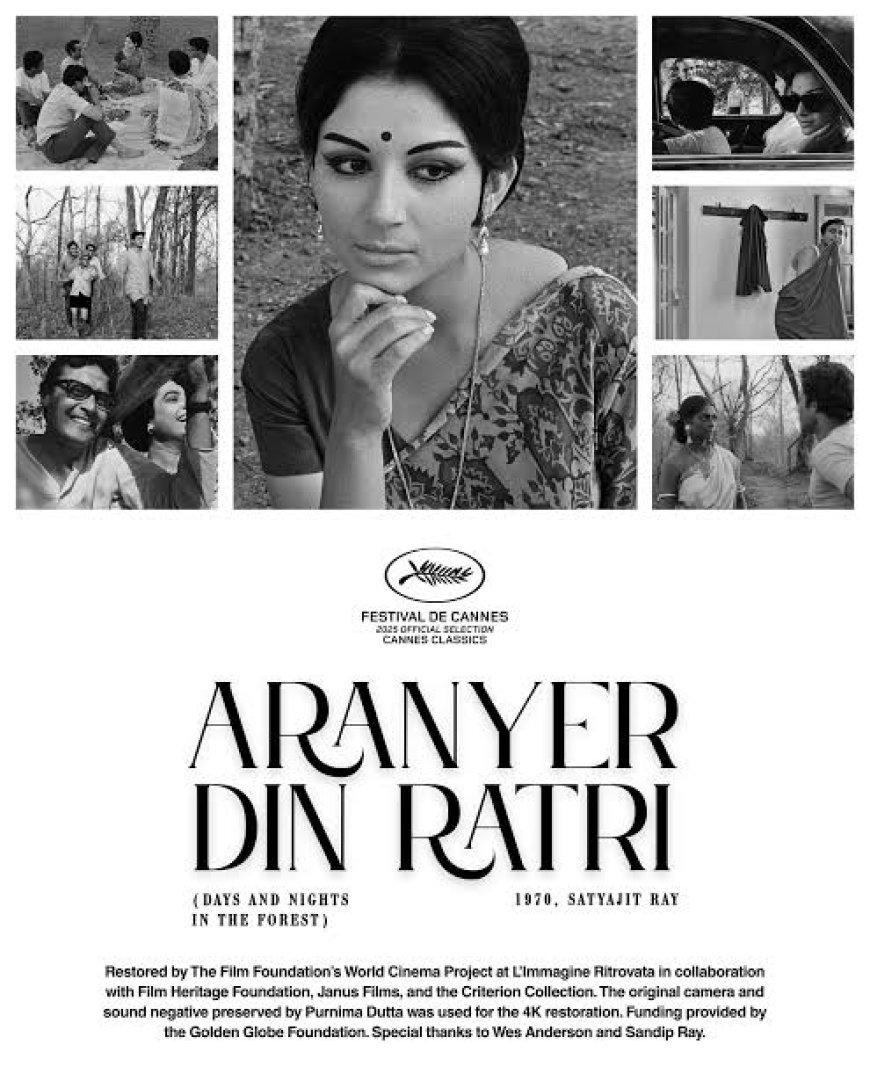

Saswata Guha writes "From Sal Forest to Spotlight: Aranyer Din Ratri and Its Cannes Resurrection"

Saswata Guha provides a long-form essay reflecting on the restored screening of Satyajit Ray’s Aranyer Din Ratri at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival. The piece delves into the film’s historical context, thematic richness, symbolic undertones, and its renewed global relevance following its recent standing ovation at Cannes.

Aranyer Din Ratri (Days and Nights in the Forest), Satyajit Ray’s 1970 classic, has once again captured global attention with its 4K restored screening at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival. The film received a standing ovation, reaffirming its timeless relevance and the enduring legacy of Ray's cinematic genius.

Overview:

In the late 1960s, as the world staggered through the aftermath of war, revolution, and moral re-evaluation, Indian cinema saw the release of a film that didn’t roar with political rhetoric or thunderous action—but whispered timeless truths through its quietude.Aranyer Din Ratri (1970), directed by Satyajit Ray and based on Sunil Gangopadhyay’s novel of the same name, is one such work.What begins as a seemingly simple tale of four urban friends embarking on a forest retreat evolves into a philosophical excavation of class, morality, masculinity, memory, and alienation. Over its 115-minute runtime, Aranyer Din Ratri does not simply entertain, it interrogates the fabric of modern Indian identity.

The Premise: Four Men and a Forest

The story follows four friends: Asim (Soumitra Chatterjee), Sanjoy (Subhendu Chatterjee), Hari (Samit Bhanja), and Shekhar (Rabi Ghosh), who escape the hustle of Calcutta for a holiday in Palamau, a remote tribal region in Bihar. At first glance, their journey seems like a familiar trope, a male bonding road trip. But Ray, ever the master of subversion, peels off the skin of leisure to expose raw emotional and psychological wounds.

Their escapade, meant to be carefree, soon brings them into contact with nature, tribal culture, and more poignantly, their own selves. Through a series of silent contemplations, fragmented conversations, awkward romantic dalliances, and drunken confessions, the forest becomes a confessional booth.

Urban Discontent and Masculine Fragility:

Each character is delicately crafted, functioning both as an individual and a metaphor.Asim, the most confident and worldly, is a symbol of bourgeois success. Yet his flirtation with Aparna (Sharmila Tagore) reveals his desperation for validation and fear of emotional vulnerability.

Sanjoy, the intellectual and conscience of the group, is burdened with moral anxiety. His discomfort during a drinking session or his distance from the flirtations displays a man conflicted between desire and decorum.

Hari, a sportsman with a broken heart, represents masculinity shaped by performance. His liaison with the tribal girl Duli (Simi Garewal) unveils a dangerous cocktail of romanticism, lust, and ignorance.

Shekhar, the comic relief, veils his loneliness with laughter. He is perhaps the most tragic of the quartet, a man whose jokes protect his unspoken anguish.

The men are all, in a sense, escapists. But unlike traditional explorers who seek external discovery, these men are running from the city’s structures, jobs, politics, relationshipsand unwittingly walk into a confrontation with the self.

Women, Wilderness, and the Other:

Ray's depiction of women in Aranyer Din Ratri is layered and critical. Aparna and her widowed sister-in-law Jaya (Kaberi Bose) are vacationing nearby, offering a gentle parallel to the four men. Aparna’s elegance and quiet strength destabilize Asim’s suave exterior. In their final conversation, her clarity cuts through his charm: “You talk a lot, but you reveal very little.” In just one line, Ray critiques the performance of modern masculinity.

Jaya, scarred by loss and guarded in affection, connects with Sanjoy. Their shared silences form a fragile bond, one that suggests the possibility of healing, even as it acknowledges pain.

And then there’s Duli, the tribal woman, who exists outside the social class and linguistic comprehension of the others. She is the “other” - exoticized, sexualized, and ultimately discarded. Hari’s encounter with her is not just a moment of misguided passion, but a representation of colonialist voyeurism. Ray does not romanticize the tribal setting. He shows the violence of gaze, the urban man intruding, consuming, and retreating.

A Forest Not Just of Trees:

The forest in Aranyer Din Ratri is not merely a location, it is a character, a metaphor, a mirror. The very act of escaping to nature suggests a desire to shed societal roles. However, instead of freedom, the forest becomes a site of revelation. It unmasks pretensions.Ray uses the forest to symbolically erase the walls of urban civilization. Within its unstructured boundaries, the characters are stripped of their usual coping mechanisms. The silence of the woods demands reflection; it does not accommodate small talk. The night scenes, with subdued lighting and ambient forest sounds, invite the viewer into this uncomfortable intimacy.

Ray’s Cinematic Language: Minimalism and Mastery:

Satyajit Ray’s direction here is at its most deceptively simple. The use of natural lighting, long takes, and unobtrusive background score (composed by Ray himself) ensures that the audience is never distracted from the characters. The camera is not intrusive; it observes.The dialogues are sparse, layered, and realistic. There are long silences, hesitant laughter, unfinished sentences—mimicking the way real people speak when they’re unsure or pretending. Ray trusts his audience to infer, to feel the undercurrents.The music is subtle, tribal rhythms contrast with the occasional western classical motif. This interplay mirrors the thematic tension: modern vs. primitive, urban vs. tribal, known vs. unknown.In a striking departure from Ray’s usual style, the film employs sudden black-and-white flashbacks. These vignettes, Sanjoy’s broken love, Hari’s past lover, Shekhar’s alienationinterrupt the naturalistic flow and plunge us into the subconscious. These moments are neither dreams nor memories, but bleeding wounds. They don’t offer answers; they deepen the mystery.It is also a cinematic technique borrowed from European modernists - Antonioni, Resnaisbut Ray tailors it to Indian sensibilities. He doesn't imitate; he translates.

A Political Film Without Politics:

Though Aranyer Din Ratri never explicitly mentions politics, it is deeply political. The class divide, the casual sexism, the portrayal of tribal communities, these are not incidental. They are statements.In an India grappling with the post-independence disillusionment, where the Nehruvian dream was beginning to crumble, Ray holds up a mirror not to politicians but to the citizens. The real crisis, he suggests, is not in Parliament, but in drawing rooms and dining tables, in the way we engage (or fail to) with the other.

Conclusion: A Journey Into the Self

Aranyer Din Ratri is not just a film, it is a quiet confrontation. It asks: Who are we when stripped of our roles? What remains when the city’s noise fades? In the rustle of leaves, the clink of whiskey glasses, the glint in Aparna’s eyes, or the unease in Hari’s gaze, Ray crafts an opera of silence.This forest is not merely a backdrop. It is a state of mind. A liminal space where the past haunts the present, where masculinity trembles, and where the wild isn’t just around, it’s within.And perhaps that’s why, when the film ended at Cannes, there was silence before the applause. Because sometimes, truth takes a moment to echo.

*****

What's Your Reaction?