Jhilli – Discards, Defining its Own Genre

'The first striking feature of the filmmaker is in choosing to direct his first film on the marginalized among the margins who, we know exist, but steer away from at all costs', writes Shoma A. Chatterji.

The word “jhilli” means ‘discards’. This sums up the substance of the film which marks the directorial debut of Ishaan Ghose. The film bagged the Best Film Award in the International Competition on Innovation in Moving Images section at the 27th Kolkata International Film Festival last year. The film breaks all rules of the three cinematic tenets of entertainment, information and education if one were to look at it closely. The entire film is set in and against Dhapa, one of the biggest dump yards in the country. The film is not exactly about the dirty, stinking, terribly scary dump yard but about the characters who have almost been born in this dump yard and have worked there all their lives and do not have any complaints about the kind of lives they live. Neither have they realized that their lives are worse than dying. They have no clue about any other kind of life or about the world that exists beyond the dump yard.

Dhapa is a locality on the fringes of East Kolkata. The area consists of landfill sites where solid waste of the city of Kolkata are dumped. "Garbage farming" is encouraged in the landfill sites. More than 40 per cent of the green vegetables in the Kolkata markets come from these lands. There are four sectors in Dhapa for dumping garbage that are filled with 2,500 tonnes of waste per day.

The landfill site at Dhapa was set up when Kolkata, then Calcutta, was the colonial capital of the British in India. A garbage train used to run along the main roads of the city collecting waste from all the big residential buildings and offices of the British administration. Since then, Kolkata’s population has grown, and so has the amount of waste it produces. The landfill has grown into an entire landscape of garbage, which stretches for miles on the eastern fringes of the city. Kolkata municipal council has tried to find a new dumping site in the city, with hopes to reclaim what could become prime real estate at Dhapa, but their proposals have been rejected by civic bodies due to objections from local residents.

One of the main characters in the film is a bone factory adjoining the dhapa dump yard. All the carcasses of animals in the city are brought here, then their bones are separated from the flesh, and thrown inside a specific machine. The bones get crushed, the skin and cartilages are separated from the fine bone grain, which becomes the final product used in many different ways. The part left out while grinding is called Jhilli. But in the film, the word extends beyond this literary meaning through visuals, colours, sound effects, jarring music and so on. The sound effects specially, invest the film with a distinct character of its own.

Bokul (Aranya Roy) is one of the few boys who grew up in the dump and knows nothing beyond. He is the unwitting protagonist of the film. He has a few friends and in between their vague tasks, exchange dirty jokes with their dialogue littered with cuss words, vulgarity and invective, as they never had the luxury of learning any other kind of language. They laugh, dance, and fight in fun and in anger, and make fun of each other including Champa who is an eunuch forever ragged by the others who try to strip her to find out what sex she is. There is a dwarf among them, Shombhu (Shombhunath De), an old man who has lived and worked right through his life but is presently out of work because of age and weakening eyesight. He is the one who informs them that the dump yard would soon give way to an amusement park. They are shocked but not much because they have no clue of the impact on their working lives. In fact, they crack jokes about the amusement park turning into a lovers’ nest with the men kissing the girls and the girls kissing the boys and having some cuddly fun.

The visuals of the terrible dirt and the dump and the carcasses of dead animals with bones scattered all across the place is often relieved with sights of crows cawing and flying in groups waiting to pounce on the carcasses below. This is also intercut, from time to time, with a plane flying across the sky, very small, very distant, like a dot passing across the clouds as Ganesh (Bitan Boswas), Bokul’s closest friend, looks up and that is his only touch with a world that is perhaps better than the one they inhabit. But he also knows that it is a world beyond his reach and even his desires.

The camera pans back to ground reality, the reality of the dirt and the squalor and the poverty where the people who live and work here have no family to go back to, no shelter to take rest in, no fancy clothes and not even enough water to have a good wash. They eat off leftovers, sometimes even picking from the waste dumped in the yard and these scenes are grisly and bizarre but factual too. When the rains come, they revel is splashing in the dirty waters filled with slush, or spray one another with the water from a spray lying here and there and this shows the change in the seasons across the film’s narrative.

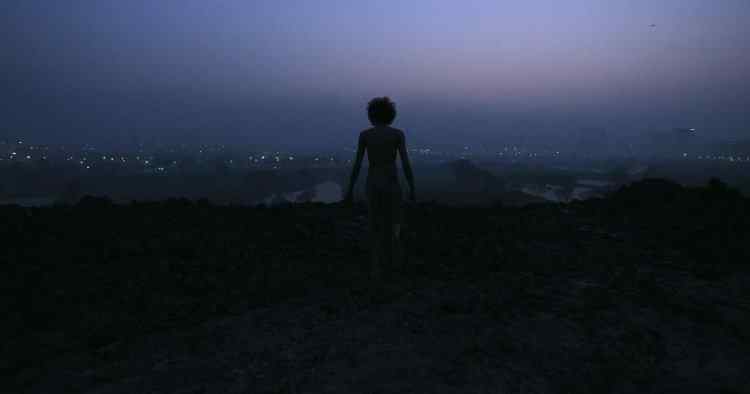

The time span is beautifully suggested through Bokul who has close cropped hair when the film opens, wearing the same pair of dirty red banyan and bluish shorts and as the film moves on, his hair grows slowly and then steadily till he has long hair, wears a beard and moustache and finally, no thanks to their addiction to polish and rubber breathed in through empty plastic bags picked from the dirt, he goes raving mad. He cannot recognize Ganesh who is genuinely worried at his state of being. Ganesh appears to be a bit sophisticated in comparison, always clad in a pair of very dirty trousers and wears a head of curls which has probably never touched a comb. Aranya Gupta gives an incredibly real performance as Bokul who turns raving mad and the camera captures him in a dark silhouette against the blue sky standing on the huge dumps of dirt. The film’s opening frames are also of the young boy running across the dump yard mainly in silhouette. Bitan Biswas as Ganesh is also very convincing and no one can imagine that they are new to films.

The first striking feature of the filmmaker is in choosing to direct his first film on the marginalized among the margins who, we know exist, but steer away from at all costs. So, the camera and the characters are placed right across the dump yards with its associations like the bone-crushing factory, the boys who have been practically born here and go about collecting the dump and discarding and/or collecting it in large bags, or, having a stint at the bone factory, or dragging the carcass of a dead cow across the dumping ground. Later, when the dump is being destroyed, one can hear the sounds and also see the huge bulldozers crushing everything in sight. When an old man dies in the dumps where he has lived, his dead body is covered in a white sheet straight into the dumps and set on fire there. The crematorium or the cemetery does not exist for them. Yet, you can see tears rolling down the cheeks of a grieving young woman close to the dead man.

The sound design is striking, disturbing and unique filled with the sounds of the bone crushing machine, the trains running right across, children of the streets running across the curved roofs of a railway station, without fear or favour, taking cruel digs at Chompa, the eunuch who finally gets back at them with a string of invectives. The shopping malls with their twinkling lights on the other side of the dump with its colourful street shops and shopping arcades, throw up a glimpse of another world. One young boy, probably an ‘outsider’ who befriended Ganesh dreams big and moves away from his friend, as he considers himself above the gang. So, there is a class schism here too. The background score is more disturbing than melodious and it is designed to be so.

So, why Dhapa at all for a debut film? ”Discomfort was the main motivation for me. Firstly, I wanted to get into a world I am not familiar with, completely different from my lived experiences. I wished to capture the suffering of people working there in a city where there is a Trump Tower just two kilometres away. Secondly, I also feel that to create anything memorable and worthwhile, discomfort should be the main point; physical and mental endurance is the most important thing. Thirdly, the whole process was a test of my own endurance in wading through dirt, the slush, the terrible smell and surviving it,” says Ishaan, son of noted filmmaker Goutam Ghose who learnt cinema by assisting him mainly with the camera but never trained in any film school.

Ishaan has also written and edited Jhilli. Visually, it is shocking because the constant barraging of the screen with scenes of the dump in the foreground, as the backdrop for the characters that people it, and through the entire footage tells us that Jhilli defines its own genre as we have not seen anything like it in a feature film.

There is a touching scene in the end when Bokul screams out, “Maa, I am hungry.” Other shocking scenes are the boys rubbing themselves against a pole to get an orgasm. Jhilli is a very scary film that shakes us out of our comfort zone and disturbs us for a long time, putting us in a stupor, as if. It is shocking in its visual impact. The sad Ganesh wanders across to the workshop with the crushing machine and finds it empty. The story comes to a close. The dump yard will soon become a history of the city that once existed and offered a lifeline to hundreds of street urchins like Bokul.

Says Ishaan, “The definition of cinema to me is to experience life to the fullest, and sharing your own joys and sorrows, with your fellow humans. I feel that’s what inspires us to watch cinema, more than anything else, it tells a lot about the filmmaker,” and on that note, we part.

“Discards” does not just imply the physical reality of the dump yard. It extends to the people, men, women and children who people it and make a life out of it for whatever it is worth or not worth. It is also a metaphor that symbolizes these human groups who live and work and play in these sub-human, almost animal-like conditions and have no complaints or dreams as they do not know of any other kind of life.

***

About the author: Dr. Shoma A. Chatterji is an Indian film scholar based in Kolkata.

What's Your Reaction?