FESTIVAL FOCUS: SIGNS 2023/In conversation with documentary filmmaker Divya Sachar

'The film "Searcher"(2022) resembles a collage at times and a personal essay at others, and despite the filmmaker's personal struggles, she transforms this simply told story into a beautiful ode to destiny and the triumph of the human spirit,' writes Dipankar Sarkar,

Dipankar Sarkar, an Indian film critic and an alumnus of FTII, Pune interviews the documentary filmmaker Divya Sachar, which unfolds many aspects of her background.

The narrative voice of Divya Sachar's 19-minute documentary Searcher (2022) comes from the filmmaker's speculative inquiries into how she developed schizophrenia and whether trauma is inherently passed down through generations. The film resembles a collage at times and a personal essay at others, and despite the filmmaker's personal struggles, she transforms this simply told story into a beautiful ode to destiny and the triumph of the human spirit.

Searcher (2022) is selected for the documentary competitive section of SIGNS 2023, held in Kerala.

How did you get interested in filmmaking?

When I was younger, I thought filmmaking was a fun way to get rich and famous. Then I went to FTII (Film and Television Institute of India, Pune), and though I had watched some art house cinema before, it was never in this intense way. I knew I was going to be an artist, though not rich and famous. Art is more attractive to me than money. After my first post-graduation (an MA from Delhi University), for my second post-grad, I had a choice between being a broadcast journalist at the Asian College of Journalism in Chennai and a filmmaker at FTII, Pune. I chose FTII because I knew I was going to be a filmmaker only, and there was no point in first being a journalist and then making films. I am glad I made that decision in favour of FTII; it was based on my father's advice. But I also like writing about films, so I practise visual arts journalism too.

The protagonist in 'Searcher' having a therapeutic conversation with the jamum tree in her courtyard adds a mythical significance to the narrative structure. Why did you choose such a medium to express your inner thoughts and concerns?

I don't like explaining my films. It's an intense film and I'd like the audience to form their own conclusions. Searcher is what I call a cine-poem or a poetry film, and not a scientific or objective fact and analysis based document, even though it borrows an element from scientific research. Also, it was new to me ,a tree having a human voice, that too of an old woman. This breaks stereotypical associations and I want to break stereotypes of all kinds because putting people, subjects or characters into stereotypes, whether in films or in real life, is pure laziness on the part of narrative makers. But having said that, when I was severely ill, I noticed that the tree was ill too, it had developed marks on all its leaves, and to my emotional mind it had then seemed that the tree was a compatriot of sorts. When I recovered the tree also recovered. So, I wanted to have a dialogue with the tree in the film.

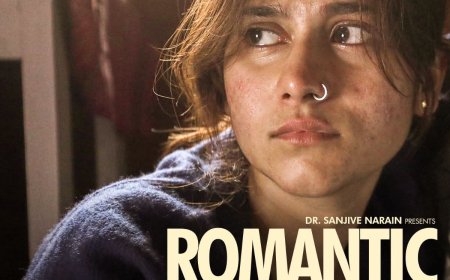

Image: filmmaker Divya Sachar

By layering the soundtrack of "Old Alabama" over the still images of the partition of India in 1947, what are you trying to express connotatively?

The soundtrack "Old Alabama" is a field recording by the late, great ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax, who documented American vernacular music. As far as I know, the song was originally a slave song, and by the time Alan Lomax recorded it, it was being sung by African American prisoners. My grandmother was also a prisoner of circumstance, having faced the brunt of the Partition and then dying young. The grindstone, for me, is a symbol of her trauma and her hardworking life. At the same time, the grindstone revolving round and round is like the mythical chakravyuh, a circular maze, in which I too was stuck because of my schizophrenia. The rotating grindstone shots give the feeling of the circularity of pain, the passing on of generational trauma to her descendant, that is me. So her trauma was due to the partition, and mine was the sudden surfacing of schizophrenia a few years ago, which turned my life upside down.

Most of the time, when the camera is inside the house, it moves, whereas while capturing the exterior shots, it remains mostly static. So, what were your thoughts during the shot design of the film?

The camera is both moving and static, both inside and outside the house. There are rotating shots of the tree outside, and there are static shots inside the house too. My thoughts during the design of the shots stemmed more from instinct than from any hard reasoning or objectivity. Like I said, I see art as poetry and intuitiveness rather than a scientific model. Also, I started as a filmmaker at FTII, but when I fell very sick, I stopped making films. Once I began getting a bit better, I began shooting still images of the old house that I live in. So I have been a still photographer for several years, and my still image practise really informs my work. A number of my friends tell me my film is like a moving image version of my Instagram account, where I post still images.

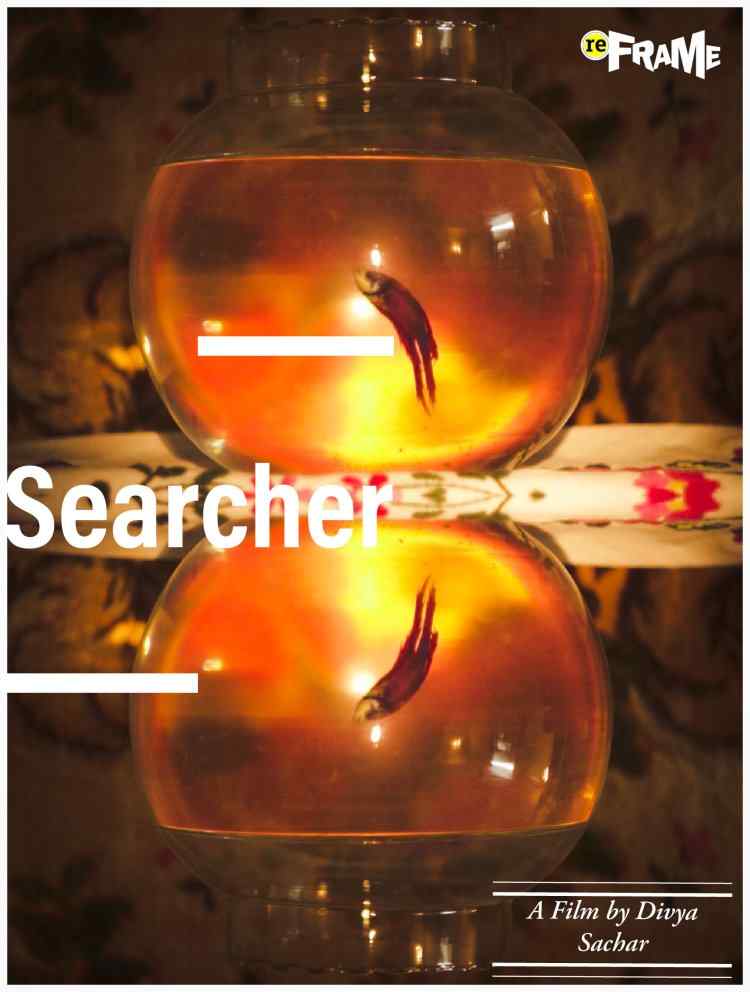

Moreover, in some of the shots, we get a brief glimpse of your image on the surface of a bowl aquarium and mirrors. Towards the end, there is also a shot of you editing a scene from the documentary. Is it some sort of symbolic association with your memories that you have established through these shots?

The film brings to the forefront the tools of my chosen art, namely the camera and the editing suite. The idea was to show the process of my recovery through the very process of making this film. That is why, by breaking the fourth wall, I acknowledge the very tools of my trade. Making the film was therapeutic for me, as was the spiritual intervention of my guru. About the other mirror shots, I don't want to explain too much, but if you listen carefully to the tree's voiceover about the cremation of my grandmother, you might get an otherworldly hint!

Given that you edited the film, how did you maintain objectivity in relation to the issues you wanted to address?

Editing is not always about pure objectivity; it is also about immersing yourself in the poetic rhythm of the film. So I was cutting on what felt right at a very primeval, instinctive level, rather than based on any analytical idea of so many seconds to this shot and so many frames of this shot. About objectivity, let me tell you this much: my guru was helping me edit the film! I owe more than just the edit to him; I owe my recovery to Sadhguru.

Lastly, how has the experience been after making such a personal film?

The experience has been therapeutic. Like I said before, the making of the film itself was therapy for me, and that's why I pay homage not just to Sadhguru, who has been instrumental to my recovery, apart from modern medicine, but I have also paid homage to the very tools of filmmaking. As artists, we are a fortunate lot. We can just dissolve our traumas and terrors into art, and our chosen art can double up as therapy. The reaction to the film has mostly been very positive, and I am a little surprised that people have liked such a personal film with so much personal imagery. There is much to be grateful for. Not everyone wants to make commercial films, and I am glad that Searcher has found an audience.

Image: Film still

***

What's Your Reaction?