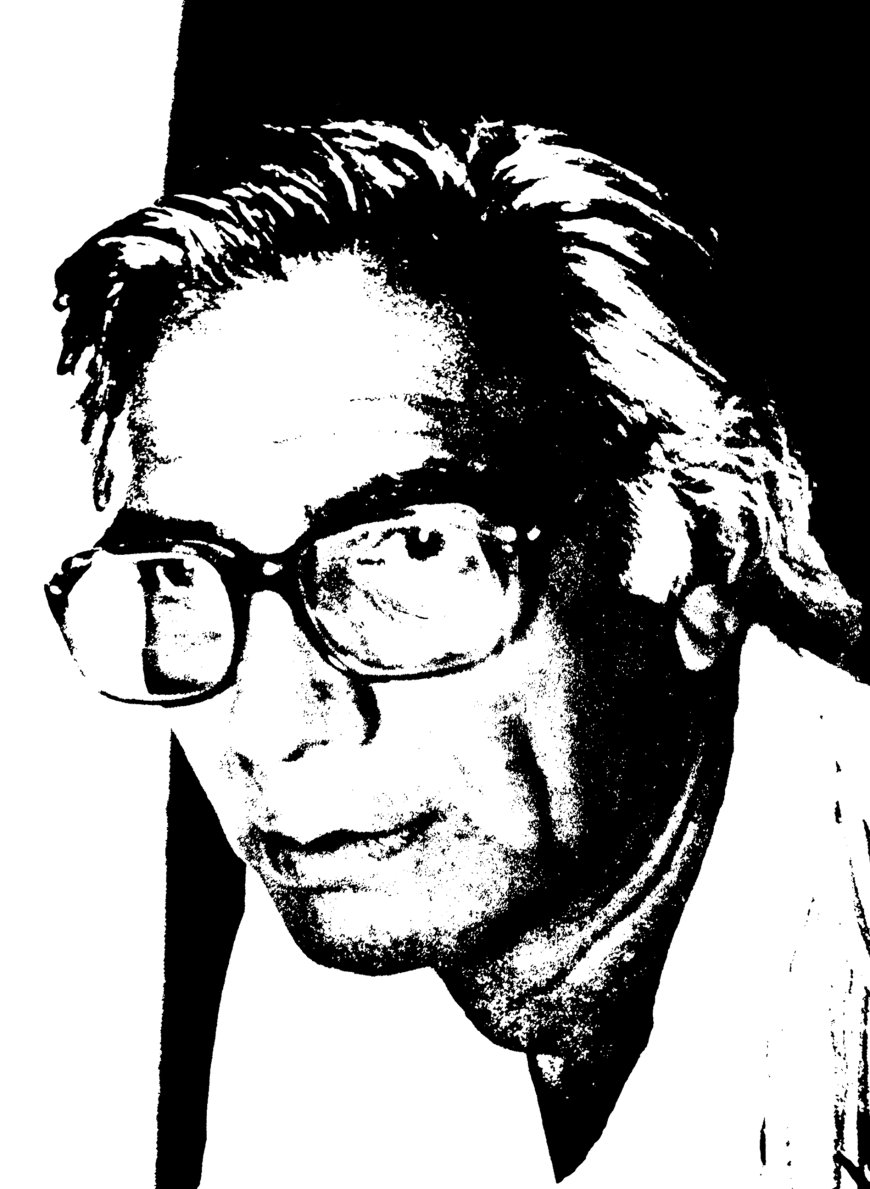

CENTENARY TRIBUTE to BANSI CHANDRAGUPTA : A DOCUMENTARY BY ARINDAM SAHA SARDAR (1924 – 1981)

Shoma A. Chatterji paid a centenary tribute to BANSI CHANDRAGUPTA, art director of the initial films of SATYAJIT RAY. The images are lent to me by ARINDAM SAHA SARDAR who has built up a wonderful archive and is also making documentary films on lost film masters.

Bansi Chandragupta is one of the most outstanding and imaginative production designers, called “art directors” at the time, in the history of Indian cinema. His centenary falls this year but except a few tribute pieces here and there, he is hardly remembered for his rich contribution to Indian cinema. He paased away in New York in 1981 but the verb “is” works in his case as there are few art directors today who can hold a candle to the kind of work he produced within very slim budgets without being paid justly for his work. This is because most of the directors he worked with, beginning to Satyajit Ray, were themselves fraught with a scarcity of funds.

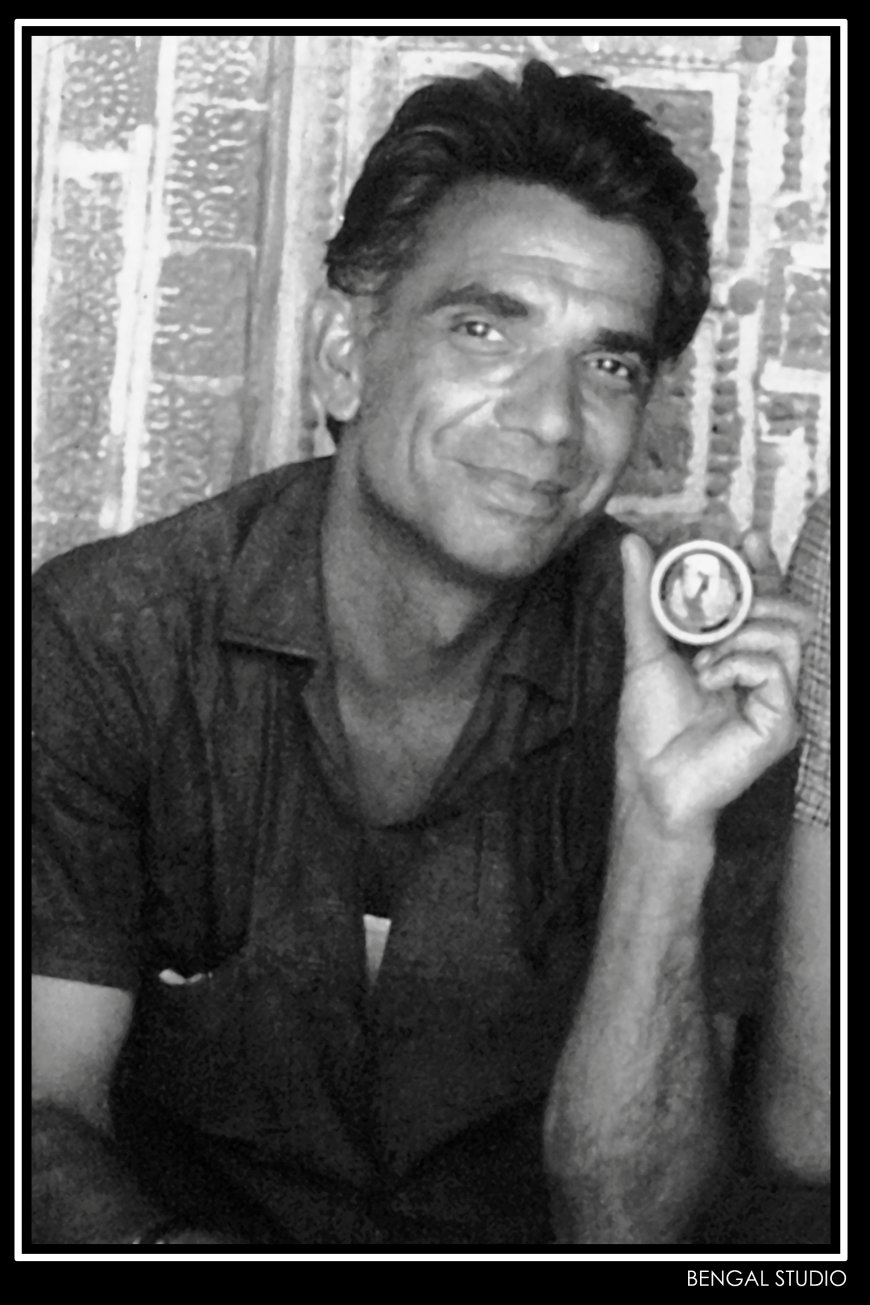

However, to fill the lacunae of a scathing absence of documentation on artists, writers, technicians of a bygone era, the young Arindam Saha Sardar, an archivist-founder of Jeebon Smriti Digital Archive has painstakingly built up an archive of ancient scripts, photographs, magazines, movie cameras, paintings and so on at his residence in the suburbs, has made a 55-minute documentary on Bansi Chandragupta.

Bansi Chandragupta is a wonderful unfolding of this simple man who hardly spoke because his mind was busy creating designs and his hands were forever engaged in doing up sets or sketches. Shot entirely in Black-and-White with the exception of clips of films originally shot in colour, the film takes us on a highly informative journey back to a time when art direction did not have modern technique that it has today. The journey is both nostalgic and emotional for those who have worked with Chandragupta and for those familiar with his work.

Chandragupta won the thrice, once for in 1972, for in 1976 and for in 1982. He was awarded the posthumously for "best technical/artistic achievement" in 1983. In an interview, when Dharmaraj was asked whether he had shot Chakra on actual locations of a slum. He said ‘yes.’ Chandragupta was very angry. He confronted Dharmaraj and asked him why he had lied because the entire film was shot on a set designed and executed by Chandragupta. “He introduced the use of Plaster-of-Paris in art direction. He went on working on the beautifully designed floors of King Halla’s court for Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne,” adds artist and art director Hiran Mitra.

“I was little when I first saw him and when it was my turn to direct my first film, I could think of no one else but Bansi Kaka as production designer,” says Aparna Sen about her first directorial film 36, Chowringhee Lane. Chandragupta did the art direction for this film, probably his last. “He actually studied many cats to fit into the interiors and the social status of Violet Stoneham’s pet cat named Toby Belch in the film. I was amazed! I never thought a production designer would go to such an extent to find the ‘right cat.’ But that was how he worked. It is very sad that he died during a foreign trip with my father and passed away suddenly,” she sums up. She dedicated her film to Bansi Chandragupta because he was no more when the film was released. Muzaffar Ali’s Umraon Jaan is anther feather in his cap. He was flooded with work after he left the Ray camp and migrated to Mumbai. His most accomplished work that marked him out were the sets he conceived, designed and executed for Ray’s Charulata, Nayak and Shatranj Ke Khilari.

Saha has interviewed cinematographer Ramananda Sengupta, filmmakers Mrinal Sen and Tarun Majumdar, cinematographer Soumendu Ray, editor Dulal Dutta, photographer Purnendu Basu, and others like Kanai Dey, Kartick Basu, Suresh Chandra Chandra, Nripen Ganguly, Amiya Sanyal, Aparna Sen and Malay Bhattacharya who narrate untold stories about Chandragupta.

Saha has worked out a wonderful combination of talking heads, clips from films on which Chandragupta had worked such as Mrinal Sen’s Baishey Srabon, Tarun Majumdar’s Balika Bodhu, Satyajit Ray’s Charulata, Pather Panchali, Apur Sansar, etc, stills and moving pictures of Bansi Chandragupta. Hrishita Majumdar and Jaytu Mondal have cinematographed and edited the film. Saha has interspersed the footage with actual drawings of sets done by the art director which makes this one of the best biographical documentaries in recent times. Chandragupta recreated the mid-nineteenth century milieu of the British general Outram and the pre-Mutiny Muslim habitats of Lucknow in Shatranj Ke Khilari. One of his classic Hindi films is Muzaffar Ali’s Umraon Jaan (1981). Other noted films are Ismail Merchant’s Mahatma and the Mad Boy (1974), James Ivory’s The Guru (1069), Kumar Shahani’s Tarang (1984), Shyam Benegal’s Kalyug (1981) and Avtar Kaul’s 27 Down.

Born in Sialkot, Chandragupta’s family, Kashmiri Pandits, shifted to Srinagar when he was a boy and his schooling was in this city. He was inspired to take on art by Shubho Tagore who he befriended in Srinagar. He came to Calcutta. “He set an example in doing everything himself, not ready to delegate any part of the work to any assistant,” said veteran art director Kartik Bose. “He had no ego hassles at all,” said cinematographer Soumendu Roy who has worked with Chandragupta for many films. “When I was about to take a shot, he would hold a reflector in place just at the right point as he was a very good photographer himself. He never felt that this was not his work and that there were others to do it,” Roy adds.

“If you remember the worn out, old door the old and bent Indir Thakrun used in Ray’s Pather Panchali, you can draw parallels between that worn out door and the worn out Indir Thakrun, both awaiting their death,” says filmmaker Moloy Bhattacharya, elaborating on how Chandragupta took great pains to ‘weather’ the old door to make it look more worn out. He burnt the lower ends of the two panels of the door so that it would look like falling off any minute. Such was the extent of his commitment to his art and his intention to be as authentic as possible,” he sums up. The very concept of ‘weathering’ to add ‘age’ to anything, a piece of furniture, a framed photograph on the wall, or, a wall itself, was perhaps created within the Indian scenario by Chandragupta.

He was always simply dressed in a half-sleeved shirt worn over a dhoti with wide, black-strapped slippers. His hair was always ruffled and his pockets were filled with papers and small notes. He hardly spoke and concentrated personally on every bit of his work so much that often, directors like Ray and Sen were fed up waiting for his finishing touches here and there before the camera could roll. His most accomplished work that marked him out were the sets he conceived, designed and executed for Ray’s Charulata, Nayak and Shatranj Ke Khilari. His design of the interior of a railway compartment for Nayak was so flawless that most viewers took it to be real.

“He introduced indigenous methods to economise on production costs without compromising on the final product,” said the late Tarun Majumdar who asked him to do the art direction for his famous film Balika Bodhu. “I had told him when I was about to sign him that we had very little money and would be able to pay him only a small amount. He agreed. As shooting progressed, I was a bit surprised to see the sets because it was a period film and the material did not come cheap. Then one of my production team informed me that Bansi-da was spending money out of the meager remuneration I had paid him for the work. Can you imagine the commitment?” he asks, wistfully.

Chandragupta said, "Art direction has two major aspects - technical and aesthetic. The first is completely the art-director's domain while the second is not only based on the theme of the film but can also influence on the film as a whole... Sometimes the creative use of furniture or props can convey certain sentiments which cannot be conveyed through dialogues... It his here that an art-director can stamp his personality ... But the art-director's freedom is limited by the attitude and calibre of the director..."

What's Your Reaction?