Utpal Dutt’s 30th Death Anniversary ( August 2023 )

Dr. Shoma A. Chatterji, a distinguished Indian film scholar and esteemed author, graciously extends her homage to the illustrious Utpal Dutt.

Utpal Dutt, actor, director, theatre scholar, elocutionist passed away on 19th August 1993. Since a major slice of the Indian film audience identify him with a lot of fun and frolic from its memory of Utpal Dutt in Hindi films, he reached much beyond that surface of fun and in Bengali cinema, villainy also. Few beyond West Bengal are aware of his scholarly knowledge and participation in theatre as an actor, a director and a group founder. He was however, well-known in international theatre for his revolutionary and innovative experimentation mostly with strong political leanings.

His career in films spans an oeuvre of more than 100 films covering forty years. It covers a colourful range of characterizations beginning from the upright and honest government officer in Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969) to Satyajit Ray’s Agantuk (1991) and Gautam Ghose’s Padma Nadir Majhi (1993.) His range covered a happy mix of the comic and the villainous in Hindi mainstream cinema. He regaled the audience as the lovelorn Bhavani Shankar Bajpai in Naram Garam smitten by the beauty of Swarup Sampat. And the audience hated him for his diabolic villainy in Shakti Samanta’s Amanush. He played the despotic dictator to the hilt in Ray’s Hirak Rajar Deshe while he used his Bengali-ised Urdu to make audiences laugh away in a delightful guest appearance in Dulal Guha’s Do Anjaane.

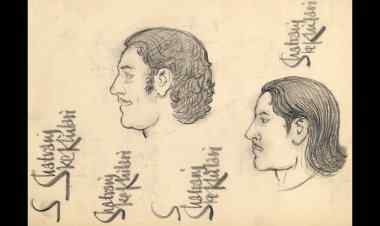

His entry into cinema was more by chance than by deliberate choice. When Shakespearana International Theatre Company led by Geoffrey Kendall left India for good, Utpal Dutt’s troupe continued to perform English plays. Once while they were performing Othello, the famous filmmaker Madhu Bose came to watch the performance. He was then looking for a leading man to do his film based on the life of the Indo-Anglian poet Michael Madhusudan Dutt. Impressed by Dutt’s interpretation of Othello, Bose offered him the role. Dutt was then looking for an opportunity to widen his canvas and to seek fresh pastures so he accepted the offer happily. This was the beginning of a long career marked by a thick portfolio of films in Hindi and Bengali while the stage remained his first love and his troupe continued its movement in serious political theatre.

Though his concept of performing Shakespeare was conventional and followed the typical classical style of proscenium performance within Kolkata, he realised that the audience comprised of an elite audience of pseudo-intellectual snobs with English education was not getting at what his dream was – to reach the “people” and what better definition of people can be there than the rural masses schooled and conditioned to jatra performance that had a lot of music, loud acting, colourful costumes and melodramatic narratives? He felt that there was a desperate need to re-play Shakespeare for the common man of the street, the urban middle-class and the semi-literate in the theatre-loving villages of Bengal. When the Kendalls left India, Dutt had formed his own group called Amateur Shakespeareans. But when he decided to concentrate on “the people” he changed the nomenclature of his group to People’s Little Theatre. He began by producing Shakespeare in Bengali translation.

Dutt formed the Brecht Society in 1948 with Satyajit Ray as president. Though Dutt borrowed the expression Epic Theatre from Bertolt Brecht, his personal interpretation of Epic Theater was greatly distanced and even opposed to Brecht’s interpretation. He accepted Brecht’s belief in the audience being ‘co-authors’ of the theatre. But he rejected the orthodoxies of ‘Epic Theater’ as he felt they would not work in India. Closer to his own theatrical tradition and Stanislavsky (the Russian theatre director and actor), Dutt wished to raise his Epic Theatre based on the reinvigorating power of myths, while Bertolt Brecht formulated his vision by subjecting this very myth to question.

In May 1990, Lancaster University organized a seminar on theatre and ideology, where Dutt represented India. In his presentation, Dutt explored the symbiotic relationship between theatre and politics and lamented the inadequate portrayal of the exploitative nature of religion. He tried to establish a link between basis and superstructure, highlighting the superstructure prevalent in ancient India.

Mrinal Sen once admiringly described Dutt as an actor who could play roles from the sublime to the ridiculous with equal flair. When asked how he made the switch from an outright commercial masala film like Fariyaad to a Ray film like Joy Baba Phelunath, Dutt said, “I have developed a technique of shutting my mind off, switching it off, rather. I will not be able to tell you even the names of the films I have acted in or even the name of the character I have just finished shooting.” Among some of his memorable films from both mainstream and off-mainstream cinema are – Bhuvan Shome, Ek Adhuri Kahani and Chorus directed by Mrinal Sen; Agantuk, Jana Aranya, Joy Baba Phelunath and Hirak Rajar Deshe directed by Satyajit Ray; Paar and Padma Nadir Maajhi directed by Gautam Ghose; Bombay Talkie and Shakespearewallah directed by James Ivory; Jukti Takko Aar Gappo directed by Ritwik Ghatak; Guddi directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee; Swami and Golmaal directed by Basu Chatterjee; Amanush directed by Shakti Samanta; and Michael Madhusudan directed by Madhu Bose, among many others. His villain in Amanush was backed by a string of theatrical tricks and turned out to be a big hit with the audience. His performance in Agantuk brought him the Best Actor Award from the Bengal Film Journalists Association in 1992.

Dutt also directed some meaningful films during his career. These were – Megh (1961) a psychological thriller, Ghoom Bhangar Gaan (1965), Jhor (1979), Baisakhi Megh (1981), Maa (1983) and Inquilab ke Baad (1984). None of these films met with any kind of commercial success but this did not seem to deter him.

Ghoom Nei, a play authored by Utpal Dutt, was staged recently in Kolkata by a dedicated theatre group. Dutt wrote the play decades ago but its resonances are loud and clear today within the top-heavy political climate we live in. Ghoom Nei is a play that challenges its audience to shake off their comfortable space, and see what life is really like among struggling and poor people whose struggles are such that it never allows them to sleep. That is why it is called Ghoom Nei meaning “no sleep.”

Public pronouncements often landed him in trouble. Dutt was arrested on December 27, 1965, on a warrant issued by the Government of West Bengal under the Preventive Detention Act. He was detained for several months, as the then-state government feared the subversive message of his play Kallol (Sound of the Waves), based on the Royal Indian Naval Mutiny of 1946, which ran to packed shows at Calcutta’s Minerva Theatre, might provoke anti-government protests in West Bengal. He was released on bail, since he was then busy shooting for the title role in Shashi Kapoor’s The Guru. Through the 1970s, three of his plays, Barricade, Dusswapner Nagari (City of Nightmares) and Ebaar Rajar Pala (Enter the King), drew crowds despite being officially banned. In 2005, forty years after the staging of Kallol, the play was revived as Gangabokshe Kallol, forming part of the state-funded ‘Utpal Dutt Natyotsav’ (Utpal Dutt Theatre Festival) on an off-shore stage, by the Hooghly River in Kolkata

As an author, Dutt wrote 22 full-length plays, 15 poster plays and 19 jatra scripts. He directed more than 60 theatrical productions and acted in thousands of shows across the state of West Bengal besides writing in-depth essays on Shakespeare, Natasamrat Girish Chandra Ghosh, Stanislavsky, Brecht and revolutionary theatre besides translating Shakespeare and Brecht. His two collections of essays, written from the fifties to the nineties, namely, On Theater and On Cinema are not just from the viewpoint of someone with a definite politics but also as a practitioner in these arts, mapping the aesthetic, political and revolutionary seas of his time in search of productions that reach out beyond the proscenium and the street and the jatra stage to touch people’s hearts, move them in certain ways and also, in some cases, initiate and inspire change.

***

What's Your Reaction?