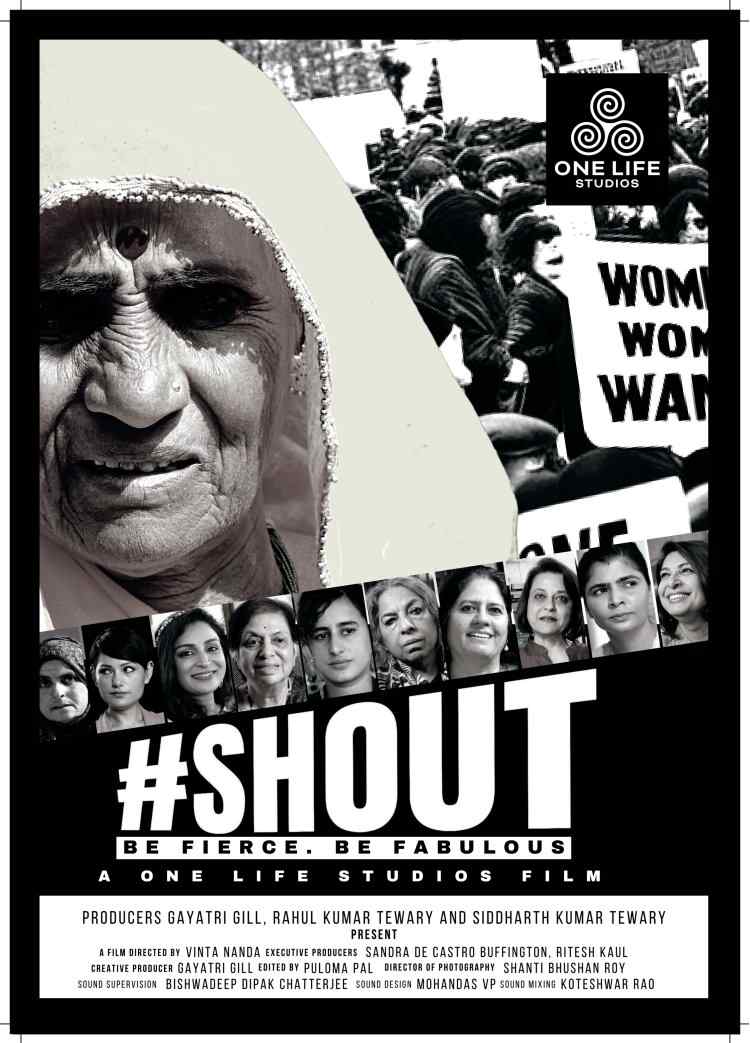

#SHOUT#A FILM ON THE MANY FACES OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN BY VINTA NANDA

Dr. Shoma A. Chatterji, an Indian film scholar and author is in conversation with VINTA NANDA, a well-known activist and media person and filmmaker

Former Director of Programming at ZEE Network, Vinta Nanda has directed a documentary feature called #Shout. She is the editor of The Daily Eye, an online media. Her critically acclaimed film, White Noise (2004), starring Rahul Bose and Keoel Purie, screened across the globe at film festivals like Karachi, Florence, Seattle and Pune is another feather in her already feathered cap. Vinta has directed many tele-series for satellite channels that were hits such as Tara, Raahein, Raahat, Aur Phir Ek Din and Milee among others. Her entertainment education work includes serials like Sheila, Kasbah, films like Anant and Aparajita and documentaries. She is a Trustee at CORO India. She opens up in a long interview about her new film #Shout.

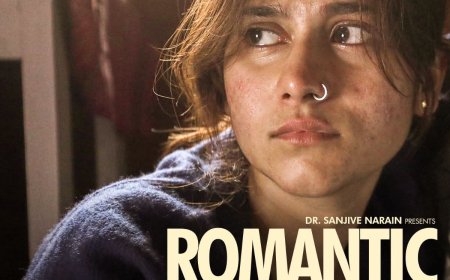

Image: VINTA NANDA

Why the title #SHOUT and why the Hashtag?

The title emerged while making the film. We were grappling with what to call the film and there were various titles that were tossed around. But, on completion of the edit, we, the producers, Gayatri Gill, Siddharth Kumar Tewary, and I, saw that the protests we had covered, and included, were signature to the narrative and that’s how #SHOUT came to us as the title. There were people, crowds, heaving populations, and then there were individuals speaking amid the frenzy we had captured – as it came together, the sound was building up to a crescendo and we realised that calling the film #SHOUT would be best. The hashtag gave it resonance with the #metoo movement, and it is also a sign of the times we live in. We need to keep the issue trending and irrespective of people listening to what we are saying or not, we must keep shouting until we are heard.

The focus is mainly on the different perspectives on rape such as Dalit versus upper class, Muslim versus Hindu, weak versus powerful and so on very clearly. Domestic violence is not covered much. Why?

Violence, suppression, dominance, discrimination, inequality and exclusion are generic terms to women’s issues, be it domestic violence, be it rape. The politics of the suppression of women and casual dismissal of women’s rights is pervasive. The thread binding us through the narrative of this film was Bhanwari Devi’s case and how the battle she fought relentlessly for years led to the promulgation of the Vishakha Guidelines in 1997, which were then superseded in 2013 by Sexual Harassment of Women at the Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act. It was during the #metoo movement of 2018 when, finally and especially in the industry of media and entertainment, Prevention Of Sexual Harassment (POSH) committees were mandated to be implemented in all places of work. This thread provided us the arc and therefore everything we covered was pertinent to the primary story we were telling. Domestic violence is important to address and cannot be made secondary or tertiary to another narrative. #SHOUT 2 is in discussion, so we have plans to go wider with the narration.

The interviews with Bhanwari Devi, Sujata Manohar and NaseemaBano, the mother of the eight-year-old little girl, add a third dimension to the film. But what obstacles did you face while asking them to cooperate? Kindly explain.

Very frankly, there were no obstacles. Everyone we approached was willing to talk. Gayatri, my producer, and I had a couple of touch points to start from. We had a formidable team of researchers in Bani Gill, Shiv Bhalla and Paroma Sadhana, and along with them were three very powerful women, deeply attached to the issues, who guided us: Namita Bhandare, Preeti Gill and Nirupama Dutt were instrumental in driving our process. Namita took us to Bhanwari Devi, Retd. Justice Sujata Manohar, Nirupama to Bant Singh, Naseema Bano and the struggle of the Dalits and minorities fighting the system, and Preeti to publishers and authors who had worked and written extensively over several decades on feminism in India intersecting with conflict.

How long did it take for you to shoot the entire film and have you got it censored yet?

We researched for about six months ,intensively, in 2019. While researching, we connected with the people we wanted to speak to and started shooting with them in January 2020. We travelled in three batches between January and March 2020, for about 40 days, in a well-planned but gruelling schedule. The last day of our shooting was in Imphal on the 14th March 2020 and we returned to Mumbai via Guwahati on the 15th March. Soon after, within a week, the first long COVID lockdown was announced. We had to abandon quite a bit of shooting that was planned, and in the two years of successive lockdowns, the editing was done entirely online. My editor Puloma Pal was in Kolkata at the time, she returned later, and we devised ways to keep on working. By the time our final cut was ready in mid-2022, the dark cloud had moved away and we could get back to studios and work on the sound, music, remixing etc. We’ve been through the censor process. As I write this to you, we are working on the couple of things they’ve asked us to alter – for instance mute the sound of protestors shouting ‘Indian Army go home,’ and take out the names of people whose cases are sub-judice. Our meeting with the team from the board, which saw the film, conveyed to us that they, too, understood the importance of the film and were greatly moved by it.

Where have you planned to screen this film as it is a long documentary wanting for theatrical screenings?

We do hope for a theatrical release to happen in a strategic way. Documentary films don’t usually make it to theatres but this might be a first – my fingers are crossed. We are also hoping for the film to run on streaming channels. Other than the above carriages,i.e. taking the film to wider audiences through mainstream pipelines, we plan to take the film directly to audiences across India – to colleges, institutes, to women and men in rural and urban India. We believe these screenings will start conversations that need to be had and the conversations will lead to the desired change.

Were you working on the foundation of a basic script? Or, did you shoot and improvise as and when and worked on the edit after everything?

Today, when I pass around the brochure, I read words and vocabulary that we’ve carried through the making of the film. While making a documentary, it is believed that you don’t need a script and that everything can be done during editing, but that’s not true. There are two stages of scripting we needed to do – one before we started shooting, which was more technical than the usual script that we call a screenplay, and the second, that our editor Puloma Pal, worked on after she had viewed the material and before she gave the film its form and structure. The role of my DOP, who had long discussions with me before we went to shooting, concluded that along with the stories that were so moving, we should capture the stillness in the parts of the country we are travelling. Both Bishwadeep Dipak Chatterjee and Mohandas VP, the sound supervisor and sound designer, were clear that the sound must be given as much importance as was being given to the imaging. Therefore the songs we recorded on the trot, the powerful sound track.

How did you fund the film and what was the budget like if you can reveal it?

The film has a substantial cost, and both Gayatri Gill and Siddharth Kumar Tewary left no stone unturned when they gave me the freedom to do as I wanted. A film like #SHOUT cannot be evaluated in terms of money. The commitment, the immersion and the time taken, are immeasurable.

The Unnao and the Hathras rapes are not there in the film nor does it even refer to the young Muslim researcher who was imprisoned without any written complaint who had come to cover the Hathras incident. The same applies to the Unnao rapes of which the third girl was also found dead recently.

These are cases we wanted to follow but due to the pandemic we stopped short in our tracks. However, like I said, #SHOUT 2 is in the planning and we will cover all the stories that we have left out or were forced to abandon. The documentation of what we have gone through and what we are going through as humans has to be complete and we will just not leave it here.

Incidents happening in West Bengal are hardly covered specially the girl whose home was burnt down because she refused to withdraw her case and was later killed nevertheless? The Bantola gang-rape incident that happened during the CPM rule in West Bengal where three women health workers were gang-raped and killed with just one survivor who kept away from the media. These cases have been brushed under the carpet and are not referred to at all. In those years, this incident was as significant as the Nirbhaya gang-rape at the time and no one was arrested and remains unresolved this this day.

We need to do so much more. #SHOUT 2 and 3 and 4, 5, 6… this journey will not end until everything that the women of India have gone through is notdocumented and brought to the mainstream, until we have seen to it that nothing will be ever forgotten.

#Me Too does not cover "silence as torture and abuse." In fact, this is so strongly internalised by the average Indian family that no one even recognises it as torture and abuse and humiliation. I am referring to families where the husband and/or his parents do not speak at all with the wife except for ordering her about. The husband uses her quite brazenly as a sex object and a producer of his son and does not have any communication with her. She keeps silent and does not voice any questions either. Why?

Exactly the point we are making in the film. Manisha Mashaal, Director of Maha Dalit Women’s Andolan, Kurukshetra, speaks piercing words in #SHOUT, “I don’t know when the media will turn to us, when there will be a #MeToo movement for us as well”. In India, the #metoo movement has just touched the surface. No doubt it has had a massive impact in terms of bringing issues surrounding sexual harassment of women at the workplace to the fore, and the establishment of POSH committees at workplaces, but we cannot ignore the fact that the woman, Bhanwari Devi, whose case triggered the promulgation of the Vishakha Guidelines, is still where she is – marginalised and excluded from the change that’s we are experiencing take place in upper crust India. That’s the challenge that lies ahead of us – how do we make the two ends meet is what we need to discuss and resolve.

***

What's Your Reaction?