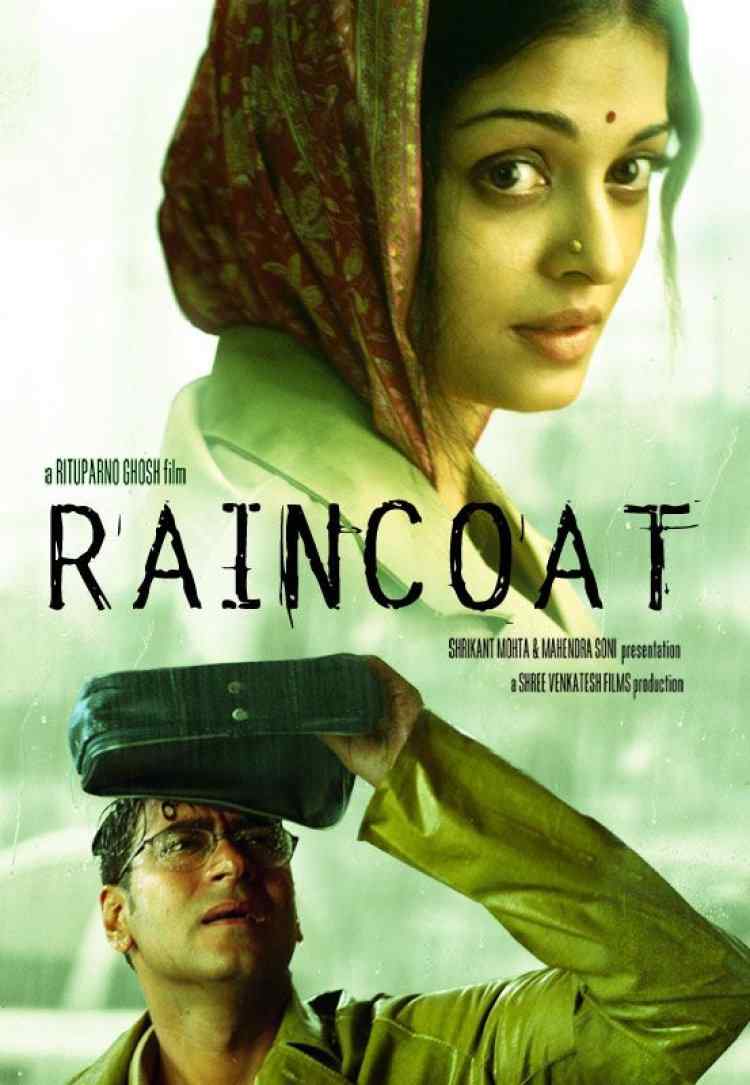

LOOKING BACK ON RITUPARNO GHOSH’S RAINCOAT

Dr. Shoma A. Chatterji , noted Indian film scholar and author, in her scholarly analysis, explores the Hindi film "RAINCOAT" directed by Rituparno Ghosh, offering a fresh perspective on its interpretation. The film's narrative drew inspiration from O'Henry's short tale "The Gift," although with a distinct Indian perspective, as skilfully interpreted by Ghosh. Despite its initial financial failure, the picture remains worthy of critical examination even though it was first released in 2004.

Rituparno Ghosh’s Hindi film Raincoat, according to the credits, is “inspired” by O’Henry’s story The Gift of the Magii. This story counts among the most outstanding among approximately 381 short stories O’Henry wrote during his brief life as a writer. It has been translated, filmed, dramatised and adapted in many languages.

Rituparno takes off from O’Henry’s original story of the exchange of ‘gifts’ by a loving husband and his wife who have no money to buy gifts and then spins his own, original story for the film. This begins with the title Raincoat which has nothing to do with O’Henry’s story. A raincoat spells out the season of the year – the monsoon that immediately places the time-setting of the film. It is an item of seasonal wear over one’s regular clothes to protect one from heavy rains. Rituparno also fixes the climate and the physical ambience of the film that preconditions the sound design – sound of thunder and lightning, sound of leashing showers, a fire engine rushing somewhere to attend to a fire alarm call. But interestingly almost the entire footage is shot indoors where rains do not enter.

French sociologist, philosopher, cultural theorist, political commentator and photographer Jean Baudrillard’s (27 July 1929 – 6 March 2007) theorised what is called the object-value system. Baudrillard’s first full-length study, Le Systeme des objets/The System of Objects (1968, 1996)[i], in its original language was published after all except one, (Ghare Baire) of Ray’s films had released that fall within the scope of this study. Except in the final section, Baudrillard approaches everyday objects – clocks, cars, chairs, cigarette lighters – as an artist or photographer as much as a sociologist.[ii] Baudrillard stated there are four ways of an object obtaining value. The four, value-making processes are as follows:

- The first is the functional value of an object; its instrumental purpose. A pen, for instance, writes; and a refrigerator cools.

- The second is the exchange value of an object; its economic value. One pen may be worth three pencils; and one refrigerator may be worth the salary earned by three months of work.

- The third is the symbolic value of an object; a value that a subject assigns to an object in relation to another subject. A pen might symbolize a student's school graduation gift or a commencement speaker's gift; or a diamond may be a symbol of publicly declared marital love.

- The last is the sign value of an object; its value within a system of objects. A particular pen may, while having no added functional benefit, signify prestige relative to another pen; a diamond ring may have no function at all, but may suggest particular social values, such as taste or class.

In Raincoat, the raincoat possesses all these four values and some more. It has use-value for Manoj Srivastava who takes it from his friend’s wife to visit Neeru, his former sweetheart who lives in Calcutta because it suddenly starts raining. It has exchange value because at some point of time, it was bought in exchange for money or its equivalent by someone. Here, it changes from one hand to another – from the friend’s wife Sheela who again, borrows it from her servant to lend to Manoj. In Neeru’s home, when Neeru has to step out to buy some food, she borrows the same raincoat. Manoj brings it back to his friend’s home and returns it to Sheela. But he finds inside the pockets, a few items of gold ornaments and guesses that Neeru put them there to help him as she has seen through his deception of success as he has seen through hers.

So, the raincoat has symbolic value beyond its use value and exchange value as stands for the nostalgic remains of the love Neeru and Manoj shared before their worlds fell apart. It has sign value too as it stands apart from a system of objects – the gutka and cigarettes Manoj is addicted to, the decaying antique furniture that crowds Neeru’s apartment, the terrible state of unwashed utensils in the kitchen, and so on. There is another small touch. When Sheela hands the raincoat to Manoj, she adds that she has put some perfume on it to wipe out the possible smell of sweat because it belongs to their servant. This shows how the raincoat is elevated to a higher social class from a lower one just with the addition of a few drops of perfume Sheela, from an elite class has put on to it. Neeru smells it later and surmises that the perfume must have come from Manoj’s girlfriend.

The raincoat in Raincoat charts the ‘journey’ of a few people – more emotional and metaphorical than geographical as it also charts the changes that take place between and among the characters along the journey. What role does the raincoat play in the film? It is at once an object of protection against Nature’s wrath, an agency of communication, a robe that triggers suspicion, a concrete symbol of fellow-feeling. On the other hand, it is emotionally and materially neutral because it belongs to someone who is no part of the story. It is lent by someone (Sheela) who does not own it to someone (Manoj) who will never own it. Later, Neeru borrows it from Manoj to go out. Yet, it functions like a post-modern Cupid in a tragic love story that once was. This is a Rituparno invention created to add to the slow-paced emotional rhythm to the film and has no place in O’Henry’s original story.

The apartment in which Neeru lives with her husband is another graphic detailing that in addition to being the main place setting and backdrop, evolves into a significant character in Raincoat It unfolds layers of the deceitful and tragic story of Neeru’s life with her perpetually ‘absent’ husband. It is a rented apartment but the rent has remained unpaid. The apartment is choc-a-bloc with furniture and knick-knacks. There is a grandfather clock with the hands showing a fixed time. Another ornate table clock rests on an ornate dressing table. An ancient typewriter rests on a window sill. A couple of marble statuettes add to the ‘décor’. The lace curtains look a bit used and old but expensive. Later, the visiting landlord spills the beans. The husband is a fraud and the family is in dire straits. The antique furniture is from a furniture shop that uses this flat as its rented godown. During the day, the same furniture is rented out by the couple to theatre groups or similar people. There is a battery-operated doorbell in a flat where there is no electricity because the bills have not been paid is used to fool sudden visitors like Manoj. A total rent of Rs.40, 000 is overdue and if they do not pay up within the next few days, the landlord will have an eviction order slapped on them.

Soon after he barges into the flat, the landlord casually speculates whether Manoj is a ‘customer’ of Neeru’s ‘services’ to find out whether her husband has now led her to the desperation of selling herself for basic survival. This hints at the woman being reduced to an ‘object’ for the ‘consumption’ of ‘customers’ in exchange for a fee. This also places her, in projection, on an equal platform with the furniture and other artefacts in the apartment that are rented out everyday to ‘temporary’ customers who give it back after use. Later, when the landlord has left, Manoj wanders across the flat to witness the terrible decay scattered around – unwashed dishes and vessels in the dirty kitchen, food left untouched, clothes hung out to dry, the terrible toilet that gives the real story away, punctured with the sounds of a rushing train somewhere outside.

Rituparno takes only the ‘gift’ element from the O’Henry story. The rest is a story of love reborn and redefined in a different time-space-culture paradigm but not reconstructed. The ‘gift’ in either case, is not really a ‘gift’ in the sense of ‘gift-giving’ at Christmas or for any festive occasion. It is a form of ‘charity’ born out of what appears to be love but has reduced itself to pity for the one you once loved but now find in desperate circumstances. When the two lovers meet after a long gap, they are living in two different worlds. ‘Charity’ might not be the right word to use. This raises the question – do the strains of love sustain between them today? Or, was Manoj chasing a love that faded away over time, over his frustrated life that failed to give him either identity or dignity or love?

***

[i] Jean Baudrillard. The System of Objects (c 1968). New York: Verso, 1996:11.

[ii] Pawlett, William: Against Banality- The Object System, the Sign System and the Consumption System, Sociology and Cultural Studies, Volume 5, Number 1 (January, 2008). This paper appears as Chapter One of William Pawlett. Jean Baudrillard: Against Banality. London and New York: Routledge, 2007.

University of Wolverhampton, UK,

What's Your Reaction?