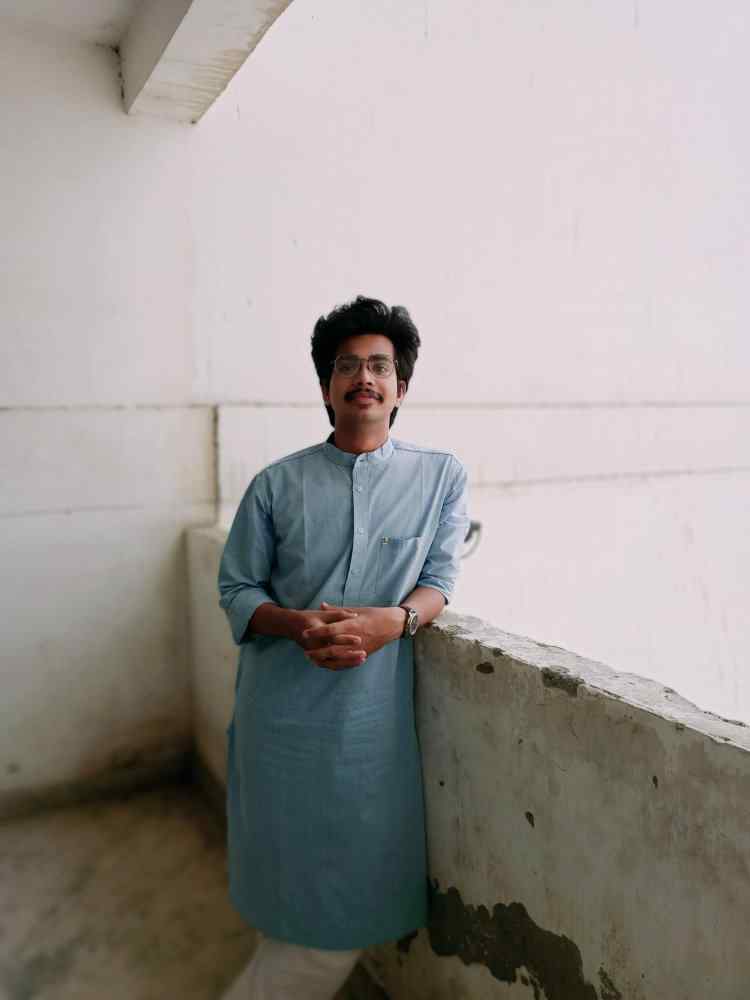

In conversation with Ehraz Asmaduz Zaman

SIGNS FESTIVAL: In A Dissent Manner (2022)

Noted Indian film critic and an alumnus of FTII, Pune, Dipankar Sarkar is in conversation with Ehraz Asmaduz Zaman.

On December 15, 2019, a large contingent of police, supported by the Rapid Action Force, entered Aligarh Muslim University's (AMU) campus under the pretense of dispersing protesters. But instead of creating a peaceful situation, the troops unleashed a brutal attack on the defenseless students with such barbarity that it displayed a sharp violation of human rights. The armed police stormed through the gates, barged inside, attacked the students, entered the buildings, opened fire on them with rubber bullets and tear gas, hauled them out, brutally beat them, destroyed their property, and hurled the harshest kinds of insults. The university quickly turned into a battleground. Using a collage of such unflinching images and testimonies from the victims, both students and professors, "In A Dissent Manner" examines the shamefully horrible incident and its repercussions on the lives of individuals whose only crime was to be students at the prestigious university.

In this interview, the filmmaker Ehraz Asmaduz Zaman tells us about his intentions and the efforts that went into making this gutsy documentary.

What motivated you to make this documentary?

I had long been wanting to make a film. It was the only thing that I wanted to do once I understood that this is the career I want to pursue. But a huge obstacle for me was that I didn't want to make a film just for the sake of it. I firmly believe that one should have something significant to say through the artform or the medium that they've chosen for themselves. Otherwise, you're doing a huge disservice to the art form itself. So I was scouring, quite desperately, for a story when it hit me that I wouldn't get a better story to tell than the terrible tragedy that happened on December 15th. I imagine people watching this documentary and believing that it grew out of this passionate need to tell the whole world what happened that night, considering the 'Muslim' identity of most of the people involved in making this film. Which is true, to some extent. But, I'd say the film was, first and foremost, born out of my sheer desperation to make a film and my stubbornness to talk about the grueling reality of our country. This realization that the world needs to see what happened that night only occurred to me while researching the film, when I understood the huge scale of brutality that occurred that night. Since I was a day scholar and wasn't present that night on campus, I had no idea about the kind of brutality that was inflicted on Muslim students that night. I'd have loved to make a romantic film or a thriller or any other film, but when you're from a minority community that's being constantly targeted, the responsibility of talking about the atrocities and oppression catches up to you sooner or later, and in my case, it happened with the decision to make this film. Also, filmmaking is such a practical profession that you need to find out the best possible story you can tell with all the resources that you have. And since I live in Aligarh, making this film was a much more practical decision, as I wouldn't have to travel anywhere with my team.

How did your collaboration with S. Farwah Rizvi help you in scripting the documentary?

Farwah is a close friend of mine, and we go back to the drama society at AMU, where we initially met. I had seen her dedication and sincerity during all the plays that she had done at the time and wanted to collaborate with her since then. We were also working on a mockumentary of sorts before the second wave of COVID but couldn't make it due to a tragedy. Anyways, when I decided that this is the film I want to make, she was the first person to come on board. I wanted her to help me with the research and find the correct structure to tell this story. At that time, she was in another city, so every day we used to meet virtually through Zoom and discuss things related to the film. These discussions, in hindsight, formed the building blocks of the film, and without her, I'd have never been able to make it. Her nuanced approach to writing also helped me create unique questions around each interviewee and their experience of that night. Hence, much of the detail that you see in the film came from her. I also want to digress a bit and say that apart from scripting and research, there were a lot of times during the production, when she became a tower of support for me, and kept me going. That's the best part about working with friends. You already have a support system in place.

The documentary begins with an aerial shot of Aligarh University, and the voiceover narration gives the feeling as if we are watching an endorsement video. But within a minute, brutal shots from the protest interrupted the serene mood. What were you trying to achieve with these contrasting shots?

That was the whole idea behind including this short segment before starting the film. It perfectly captures the abruptness of the incident and gives a sense of what was at stake that night. Barging into such a large campus is no small feat, and this was the only way I could emphasize it. Also, this small segment allows the viewers to see the legacy of Aligarh Muslim University and the kind of importance it holds in the lives of many Muslims. In a way, it also works by giving a brief context to people who don't know much about the university so that they can grasp the whole film in a more holistic sense. Initially, it wasn't in the film, and we added it only after showing it to a few people outside the university, who told us that since they didn't know anything about the university, it was hard for them to feel the loss. Only then did we think it'd benefit the film if we gave a glimpse of the university in the beginning. The documentary is constructed mostly by juxtaposing the horrific shots of what happened on the fateful night of December 15, 2019 in the AMU with interviews of individuals who have undergone the atrocities as well as individuals from the institute. How did you arrive at the structure? From the start, my approach was to make a film that doesn't shy away from showing anything and is very direct in its approach. I didn't want to complicate the narrative with any external elements or aestheticize the struggles of the victims. This decision was also backed by my little to no experience in filmmaking, and I thought that a direct narrative with only footage and interviews would be the best way for me to go about this film. Another big reason was that since we started making this film two years after the incident, having this sort of direct approach allowed us to show the events as it unfolded that night. It helped in giving an idea of everything that happened that night in a sequential order.

I agree that the perpetrators who unleashed such violent acts on the students and the administrators who had allowed the police to enter the premises of the university would find it difficult to appear before the camera and express their reason behind this mayhem. But that would have also added a perspective to the narrative, and as a viewer, we would also get to hear their share of the story.

This is something that we initially took into consideration while making the film. We wanted to include bits of the narrative that the state and the police were spinning around this whole incident. As a matter of fact, we did interview someone who works in the university administration, but his whole perspective was built around blaming the students for whatever happened that night. It wasn't as if he was in favor of what happened, but he did put a lot of blame on the students. Now, we didn't use it because there was absolutely no space for a middle ground in our film. We didn't want to include the reasoning of the other side because we thought it would dilute the many statements of the victims in some way or another. This film was born out of a student movement, and showing their perspective and ideology was our foremost responsibility. Showing the other side would mean that the film is taking an objective stand on the whole issue by showing both sides, which isn't what I intended to do. I believe there's nothing wrong with taking a side while telling a story, especially in a case where an objective stance would have harmed the struggles of my community.

In one of the scenes, activist and lawyer Fawaz Shaheen informs us that when a missing list of students was released to the media, both the university and the police admitted they were detained. So, what role did the media play in this atrocious incident?

Since this incident happened alongside the police brutality in Jamia Millia Islamia, AMU didn't get that much attention. Only a few independent media outlets covered the incident, and only briefly. Mostly it was mentioned in passing whenever there was a story on the Jamia incident. Apart from this, there's no point in talking about the mainstream media because, without even seeing their coverage, one can tell the kind of stand they would have on this incident, which only harmed the community. But yes, in regards to what Fawaz Shaheen said in the film, it was because the list of detainees was released in the local media circle that the university admitted to their detention.

Did you face any hurdles or obstacles during the making of this documentary?

From the beginning, we were very discreet with how we went about the shoot of the film. I had a very small team, and we shot the film without much fuss. That's the reason no one took notice and we could complete the production. I'm sure if the administration got to know that we were making this documentary, they'd have tried their best to intervene and cause trouble. The only major obstacle we faced was convincing people to speak in front of the camera, and since this was our first film, we did have a bit of trouble approaching people in the right way. Sometimes we'd go to meet someone and they'd tell us everything, but when it came to recording their interview, they'd outright reject us. Such was the fear among Muslims regarding CAA-NRC that they didn't want anything to do with the film. To win the confidence of students and to respect their decision was the biggest challenge we faced while making the film.

What are your plans to show this documentary to more and more people?

Apart from sending to different film festivals, now I'm trying to conduct screenings inside different campuses. Since it's a film about a student movement, campuses are the perfect platform for me. I had a screening at SRFTI, and I plan to do the same on a few campuses in Delhi. But first, I want to screen it at AMU, as we haven't been able to do so. We tried approaching a few people, but they all advised against it. But I feel that if it can't be shown on the campus where it all happened and where this film was born, it's pointless. Hopefully we'll get a chance to screen it there.

***

What's Your Reaction?