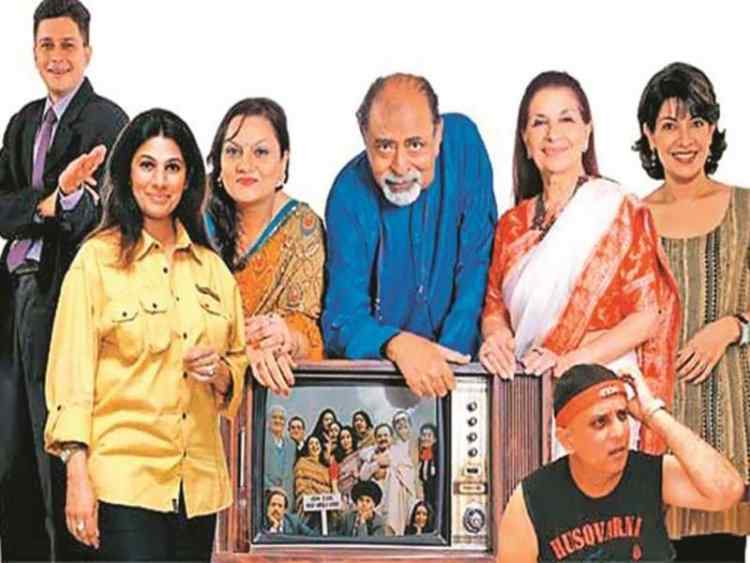

HUM LOG CELEBRATES FORTY YEARS A LOOK AT THE WOMEN IN HUM LOG

Dr. Shoma A. Chatterji writes about the 40th anniversary of India's first mega-soap, Hum Log.

India’s first mega-soap Hum Log, completes 40 years. Doordarshan, owned, managed and produced by the government, the only television channel at that time, floated a soap opera called Hum Log (We People) produced by a private company to raise women's status and reduce the mistreatment of women. It attacked the dowry system, encouraged women to get educated, decide how many children they would have, and promoted gender equality in the workplace.

Following a Mexican trip in 1982, the idea for Hum Log ("People Like Us") was developed by the then-Information and Broadcasting Minister, Vasant Sathe in collaboration with writer Manohar Sham Joshi and a little-known filmmaker, P. Kumar Vasudev. It was in response to a Mexican soap opera structured to spread developmental messages through episodic story-telling. Hum Log began with the romantic yearnings of a modest young man from a poor family for the beautiful and spoilt daughter of a wealthy widower. It narrated an epic story of one family with sub-plots involving brothers and sisters, aunts, uncles and grandparents. The grandparent was the patriarchal head of the family, but the reins were almost completely controlled by his wife, the grandmother. The grandfather’s only son Basessar, was a talented singer whose love for the bottle had turned him into a wastrel. Basessar’s five children, comprised of two sons and three daughters, and his submissive wife made up the extended family unit.

The TV viewing audience in India increased from 30 million in 1983 to 80 million in 1987. Hum Log was broadcast during this expansion, when television was new for many. The Hum Log characters seemed real to the audience. Millions of viewers identified with them. Viewers sent more than 400,000 letters, many of them addressed to the characters rather than to the actors and actresses. Many of these viewers identified with one or more of the characters, and many commented on the social issues raised by the show. The producers were taken aback by the extent of its popularity. There were no stars. The young people who played the leading roles had no acting experience. The other actors were from amateur theatre in Delhi. Overnight, India's first television stars were born. The actors were mobbed in the streets, overwhelmed with awards and accolades. It was as if people were yearning for situations and characters they could identify with.

The tremendous response to Hum Log opened the floodgates. Televiewers have been hooked on it and advertisers called for more serials of the same kind. Hopeful young film-makers offered to make them. The authorities, finding that advertising could painlessly provide the immense amount of capital required for large-scale expansion, threw open television to advertising, going against the principles and policies they had laid down earlier.

But whose ‘development’ was the serial aiming it? If it was the development of women, then it was self-defeating because the women were heavily tinged with the politics of patriarchy. Research on Hum Log indicated that ethnicity, geographical residence, gender, and Hindi language fluency were significant determinants of beliefs about gender equality.[i] The subservience of women is considered socially and culturally appropriate by many Indians, but not by all. One intended negative role model in Hum Log was Bhagwanti, the mother of the Hum Log family. Bhagwanti was a subservient, self-sacrificing, traditional Indian taken advantage of and abused because she always put the needs of others first. Hum Log's producers intended that viewers would translate Bhagwanti's suffering into a message for gender equality. However, 80 percent of the women who viewed Hum Log chose Bhagwanti as a positive role model.[ii] Many men indicated they felt that India needed more women like Bhagwanti. Thus, Bhagwanti's depiction as a subservient woman was received as a prosocial message rather than an antisocial one.

Even the marginal character, Sumitra Didi, the in-charge of the women’s centre who acted in and directed street plays focussing on the derogatory position of women, was reportedly a happily married woman in personal life (in the serial). Dr. Aparna, who took Chhutki under her care, was a successful doctor married to her professor husband. The tragic song of pathos that ran like an undercurrent spoke of her childlessness, suggesting that a successful career was no substitute for motherhood.

The second daughter Majhli tried to strike it out on her own, leave the home without the family’s consent, and went to Mumbai. Majhli’s ‘problem’ was her over-riding ambition, her desperate desire to break free of the stagnant middle class milieu and the vicious circle of poverty, blind belief and out-dated values that threaten to annihilate young and old alike. Such ambition should, according to the show, necessarily incite nemesis – Majhli must be punished for thinking big if the country’s sense of values is to be sustained and celebrated. So, she had to come back, repentant and sorry for her ‘misdemeanors.’ Viewers were happy. Dadimaa, the matriarch, was shrewish, greedy, proud and an oppressive mother-in-law to Bhagwanti. She did not accept Lallu’s wife Usha Rani’s assertive behaviour. Her husband was wise and selfless, and often argued on his granddaughters’ and his daughter-in-law’s behalf. The youngest son’s girlfriend Kamya was a rich and spoilt young brat. Badki, the eldest of three daughters, was strong and steady. But her strength slipped after she married her doctor boyfriend. Chhutki came to terms with her independence only when she stepped out of her biological family.

The women in Hum Log were too starched and dyed in Khadi. In keeping with Gandhian ideology, the Hum Log women took up jobs or pursued careers, but such jobs were not in conflict with their wife-mother-daughter role within the family. Kamya, the spoilt daughter of a millionaire who the youngest son fell in love with, was the only woman who had the guts to leave her debauch husband. Yet, looked at in retrospect, despite her education and modern upbringing, she was gullible to the point of being stupid.

On the streets of North India, shopkeepers and merchants closed their stores early to celebrate the wedding of Badki and Ashwini. An average of 50 million people watched each of the 159 episodes during the 17-month run in 1984 and 1985--the largest audience ever for a television programme in India till then. Hum Log was stimulated by David Poindexter, president, Population Communications International, who arranged for Mexican telenovela producer Miguel Sabido to conduct a seminar for Indian broadcasters on family planning soap operas. To evaluate the impact of Hum Log, 1,170 viewers were surveyed after the series ended. 500 of these letters were analyzed. The audience liked the show but felt that its educational impact was slight. Approximately 8% of the letters analyzed implied some behavior change. Some opined that Hum Log had led women to seek help from women's welfare organizations. Enrollment of potential eye donors increased after the issue was mentioned. Changes in family planning behavior were not commented on. These letter writers might not be a reflection of the average viewer, given the huge size of the viewing audience. But even a small percentage change meant a large number of people responded to the show. Hum Log was evaluated by researchers from the Annenberg School of Communications at the University of Southern California.

When Hum Log was re-telecast on the national channel after a decade-long gap, sponsored by Proctor and Gamble, and trimmed down to 52 from its original 159 episodes, it could no longer revive its earlier magic. Viewers had in the meantime been fed on a generous diet of serials with strong and courageous characters such as Stree, Udaan, Adhikar, Pukaar, and Draupadi in Mahabharat. Even the lay viewer was not prepared to brook the wet-rag, happy-to-be-knocked-around attitude of Majhli’s mother Bhagwanti, or the conformist and convenient ‘rebellions’ of Badki and Chhutki, and most importantly, the negative emphasis placed on Majhli’s character.

Have things changed for women on television for the better? Sociologist Yogendra Singh believes that viewer identification is linked to the basic question of human identity and the search for a role model in the larger context. “It has to do with the ideals, character, style we would ideally want to have. So all those middle-class women whose husbands were fooling around would actually want to be a Priya,” he says of Saans, a very popular serial directed and produced by Neena Gupta[iii]. This explains the cult following some soap stars command. Viewer responses often force the growth of a character in a different direction than how it was originally conceived of. Along with audience identification, there is character-identification with the actress who plays the character over a long period of time. The politics of representation somewhere along the way, merges with the politics of identification firstly, of the audience with the character, and then, of the actress with the character.

The sanctioning of the notion of women as autonomous and equal citizens while also endorsing the idea that women are around to be gazed at, is the contradiction that lessened our potential since the days of Hum Log and Buniyaad followed by Junoon and Swabhimaan. Even a strong and well-made serial like Udaan could not make a long-term impact on viewers. Nothing has changed for the better. In some ways, television has fostered the spread of the liberation movement through its vast amount of coverage of women through seemingly ‘progressive’ talk shows, discussions, debate and detailed news reports. At the same time, television has done more harm than good to women's potential as individuals by putting female conformity to convention and tradition on the forefront.

The unprecedented success of serials on satellite channels like Kyonki Saas Bhi Kabhie Bahu Thi upset the apple cart. Every satellite channel flooded the small screen with serials whose names were giveaways of this sudden and fanatic obsession for the ideal Indian bahu theme. Kalash, Shagun, Dulhan, Bahuraniyan, Mehendi Tere Naam Ki, Shehnai, Kabhi Sautan Kabhi Saheli, Ghar Ek Mandir, Kahani Ghar Ghar Ki, are some. This underscores a conscious resurgence and upholding of the sati-savitri mode perpetuated by mainstream cinema. The alphabet ‘K’ ceased being the logo for serials projecting reactionary and patriarchal stereotypes of women where the deviant female is evil and the conforming woman is the ideal. The ‘evil’ woman is as much a stereotype as the good woman. There are hardly any grey areas between these polarities.

The question is – how long do we have to wait for television to hold up a mirror to us instead of having to/forced to look at unrealistic and exaggerated images of a conformist and convenient brand of ‘femininity’ being spouted forth everyday, reinforcing and perpetuating stereotypical, on-screen images of women created by real and successful women?

***

[i] Brown, William J., and Arvind Singhal. Prosocial Effects of Entertainment Television in India, Asian Journal of Communication 1 (1990): 113-35.

[ii] Singhal, Arvind, and Everett M. Rogers. Prosocial Television for Development in India. Public Communication Campaigns. Ed. Ronald E. Rice and Charles K. Atkin. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1989: 331-50.

[iii] Ghosh, Rupali: People Like Us, The Telegraph, Kolkata, February 18, 2001; Look, Women III.

What's Your Reaction?