Parthajit Baruah on Documentary Films: Alternative Voices and Exploratory Praxes

British documentary film-maker and film historian Paul Rotha believes that ‘documentary left the confines of fiction for wider fields of actuality, where the spontaneity of natural behaviour has been recognised as a cinematic quality and sound is used creatively rather than reproductively. This attitude is, of course, the technical basis of the documentary film.’

Theoretically, the notion of documentary making has got a tremendous transformation with times. Earlier, documentaries were nothing but the short newsreels, records of current events, or travelogues which were known as ‘actualities’. The Lumiere Brothers’ first attempts to shoot the actual event or activities e.g., a train entering a station, factory workers leaving a plant, etc. were such examples. But after almost two decades, Robert Flaherty made the first narrative documentary with an ethnographic look Nanook of the North (1922), portraying the harsh life of Canadian Inuit Eskimos living in the Arctic. Later he made a landmark documentary film Moana (1926) about Samoan Pacific islanders. This was the time when John Grierson coined the term ‘documentary’ while reviewing Flaherty’s Moana (1926).

Even during World War II, documentary films were used as the tools to propagate Nazi’s ideology and one such propagandistic documentary was Triumph of the Will (1935) that records the 1934 Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg. In response to this film, the US War Department commissioned the Italian American film director, Frank Russell Capra to direct documentaries to justify the US involvement in World War II.

But a recent shift in cultural, technological, stylistic, and social aspects has been discerned in the documentary filmmaking. The documentary-filmmakers in India, who are a part of the new transformations, are keen to use the form as tools to speak of the unheard stories of the margins, crisis of identity and the lives of the common people. They address issues like politics; power, race, gender, and voice of the margins which are otherwise remain unanswered. Documentary filmmakers like Anand Patwardhan, Pankaj Butalia, have addressed these local/marginal issues to represent their universal or global relevance.

Anand Patwardhan, a distinguished Indian documentary maker, deals with the political and social issues in his documentary War and Peace (2002), but he goes beyond the reality to narrate a story of rural people who reside in remote villages like Khetolai, the site of nuclear tests. Following the Pokhran-II tests, India became the sixth country to join the nuclear club. When the whole country was celebrating following the Pokhran-II tests, villagers of Khetolai and Pokhran were fighting with lives due to the dire impact of the Pokhran-II tests. Patwardhan zooms in on the complications that the villagers encountered after the Pokhran-II tests. His interview of a resident of the village Bhera Ram Bhismoi reveals a harsh truth of the so-called ‘success story’. When the then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee visited the site, the local people of Khetolai demonstrated a protest with banners like “We want permanent hospitals in Khetolai”. Villagers of that site believe that money invested for the test, could have been for the development of the poor. The resident of the site believe that they have been badly affected by radioactive fallout. This documentary is a scathing attack on those who wish to bring peace through war.

Documentary filmmaker Pankaj Butalia has taken the identity crisis of the indigenous people and their constant struggle for their identity as the themes of his documentaries ‘An Island of Hope (2010)’ and “Assam: A Landscape of Neglect” (2015). In the opening of the documentary, Butalia mentions that forty years after Chakmas were expelled from their land, a group of young ‘Chakmas’ started ‘Sneha’ School in Changland . History says that in 1964 owing to communal violence, Chakmas were forced to migrate from Bangladesh to Arunachal Pradesh. The government offered them valid migration certificates, but still they constantly faced severe social discrimination. In 1994, an anti-Chakma wave popped up in Arunachal, and then they were harassed.

In his second documentary, “Assam: A Landscape of Neglect”, Butalia states that there are two dominant narratives that characterize in Assam , one is a deep sense of resentment at being neglected and second is a fear of engulfment. Butalia raises questions on the identity crisis or the question of ‘Who is indigenous or ‘Outsider’. The filmmaker refers in the documentary that the British took large tracts of lands to establish tea- plantation and brought labourers from all over the country. These labourers have been working since the British rule, but today none knows who is an outsider, and apparently, it seems, all are all outsiders. In the documentary, Hridayananda Agarwala says: People tend to ask where a person comes from, rather than what he does. This is the habit of nature”.

Again, Butalia refers to the immigrant Muslims of the Char Chapori who reside by the Brahmaputra river and its tributaries of Assam. During the Bangladesh Liberation War, thousands of refugees came to North-East India. They are known as ‘outsiders’ in the new states who came in search of a living.

In the documentary, Butalia again refers to the Karbis, one of the major ethnic tribes of Assam. The indigenous people of Assam are now facing the question of identity, and is precisely surfaced in the words of Elwin Teron, a Karbi man. Teron says:

‘When the Assam Accord was signed in 1985, there was nothing in favour of the tribal people. People of hills and plains have conflicts of interest – socially, politically and economically. This is the reason why Assam has so many changes. There is something in the minds of the indigenous people, this is the silent resentment.”

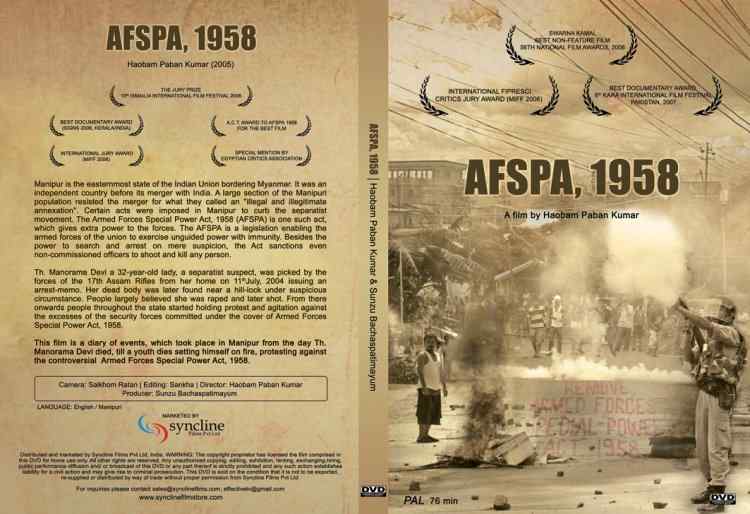

Haobam Paban Kumar’s documentaries like “AFSPA 1958” and “Phum Shang” (Floating Life) have gone beyond to quest for the truth. In “Phum Shang” (Floating Life), Paban shows how the government of Manipur government burnt down hundreds of huts in Loktak, the largest freshwater lake in North East India making the local people responsible for polluting the lake. His documentary shows how the locals were miserably displaced and how they fought against the authorities . His quest to find out truth through this documentary is an example of human story.

Now, my own perception on the meaning of documentary filmmaking is that documentary films are not the photographic representation of the reality but it must go beyond the ‘reality’ to find out the ‘truth’.

What's Your Reaction?