CAN BOLLYWOOD FILMS TEACH US ABOUT COURTS, LAW AND JUSTICE?

Dr. Shoma A. Chatterji, a renowned Indian film critic and author, has written an intriguing examination of law, tribunals, and justice as depicted in Bollywood films.

This article is inspired by the wonderful OTT feature release of the film Sirf Ek Hi Banda Kafi Hai which is basically a courtroom drama which presents a fictionalized format of the Asaram Bapu case filed, fought and won by a juvenile victim of his having molested and raped her in a room in one of his many ashrams. Jailed under the POCSO Act, Asaram Bapu failed to defend himself against the prosecution lawyer P.C. Solanki in a Jodhpur Court for five long years, beginning in 2013 and ending in 2018 during which several witnesses appeared to speak against the Godman were either killed or went missing. Right now, according to newspaper reports, the victim and her parents are living in an undisclosed place with the police having doubled the family’s security due to continuous threats to their lives.

The film stands out because it presents an authentic scene of a courtroom and treats the courtroom and ones inside it with the respect it deserves. All this is heightened by the excellent performances of Manoj Bajpeyee as the prosecution lawyer P.C. Solanki, Adrija Sinha who plays the rape victim and every other actor I the entire dramatic representation of one of the most significant and scandalous cases in recent history.

There can be no argument about the fact that cinema is a cultural product that is dynamic and active that creates, sustains, evolves and sometimes destroys its negotiating relationship with its audience. On the one hand, practitioners of cinema like to call it an ‘art’ form that embraces and interweaves other performing and expressive art forms such as music, dance, drama, poetry, photography, painting and sculpture. On the other, it is also a science that combines technical inputs, imagination and execution such as cinematography, editing, sound, light, props, locations, settings and so on. A combination of the ‘art’ that is cinema and the ‘sciences’ that make its production possible defines a socio-cultural product that impacts on the audience –momentarily, temporarily or permanently depending on the depth of its entertainment, cultural, political and historical value.

The two significant questions here are (a) Do cinematic practices and imperatives create a ‘reel world’ view of the law or (b) Are there some films that replicate the real world of the court system in and through cinema? In her paper, Legal Ethics – Prime Time and Real Time, Deborah L. Rhode (Berkeley Journal of Entertainment and Sports Law, Vol.I Issue 2, Symposium Issue, May 2012) argues that cinema can become a very good medium to teach about the law and judiciary because “stories speak to our emotion as well as intellect, they can provide a deeper, sharper, and more intense understanding than traditional law school approaches”.[1] She further adds: “One other justification for looking at legal ethics through a fictional lens is that it supplies a foundation for lifelong learning.”

Earlier, most Bollywood courtroom dramas were almost always adapted, Indianised versions of good Hollywood films such as Kasoor (2001) from the Jagged Edge (1985), Deewangee (2002) loosely adapted from Primal Fear (1996), or Shaurya (2008), a very close adaptation of A Few Good Men (1992). Recently however, filmmakers have picked real-life courtroom case histories scattered around waiting to be picked for celluloid interpretations. Kanoon Kya Karega (1984), plagiarised from the famous Hollywood thriller Cape Fear (Martin Scorsese in 1991), was a crime thriller with the fear of rape running like a constant thread throughout the film. Aitraaz (2004) adapted from Disclosure was so Indianised that one could not identify the original it was taken from. This is matched with the serious approach of the two defence lawyers Annu Kapoor and Kareena Kapoor. But Aitraaz was a complete commercial package with songs, dance, romance, murder, sex and the exaggerated courtroom drama that is pure fiction. The courtroom scenes with prosecution lawyer Paresh Rawal soaked with satire and fun and the comic is far removed from a real courtroom scene.

The visual representation of the courtroom itself is filled with inaccuracies that send across mistaken perceptions of the court among the audience. Satyajit Bhatkal who was once a lawyer and is currently into production of television software says that the courtroom is visually abused. Writes Bhatkal: “The worst abuse has been in art direction - practically every courtroom has been shot with the statue of the goddess of justice blindfolded and holding scales - typically perched on the judge's desk! I have practised law for ten long years in courtrooms all over the great state of Maharashtra and also in several parts of India and have yet to encounter the said goddess!”

The other abuses - the compulsory photographs of Gandhiji, Nehru, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose and the Satyameva Jayate emblazoned behind the judge - are part of the fantastic presentation of courtrooms. This art direction is wholly consistent with the fantastic conduct of leading characters in the courtroom.

Like other stereotypes in Bollywood, lawyers have often been caricatured in films. A cop will always arrive late at a crime scene; a doctor will always ask the relatives of his patient to have faith in God; and a judge will always be shown as saying “Order, order, order,” as he bangs his gavel to warn noisemakers in his courtroom. “Who uses the gavel? I am yet to see any judge of a lower or a higher court use it,” scoffs Akhileshwar Dayal, senior advocate, district and sessions court, Meerut. “Hindi cinema is far removed from reality when it comes to depicting courtroom scenes,” Dayal adds.

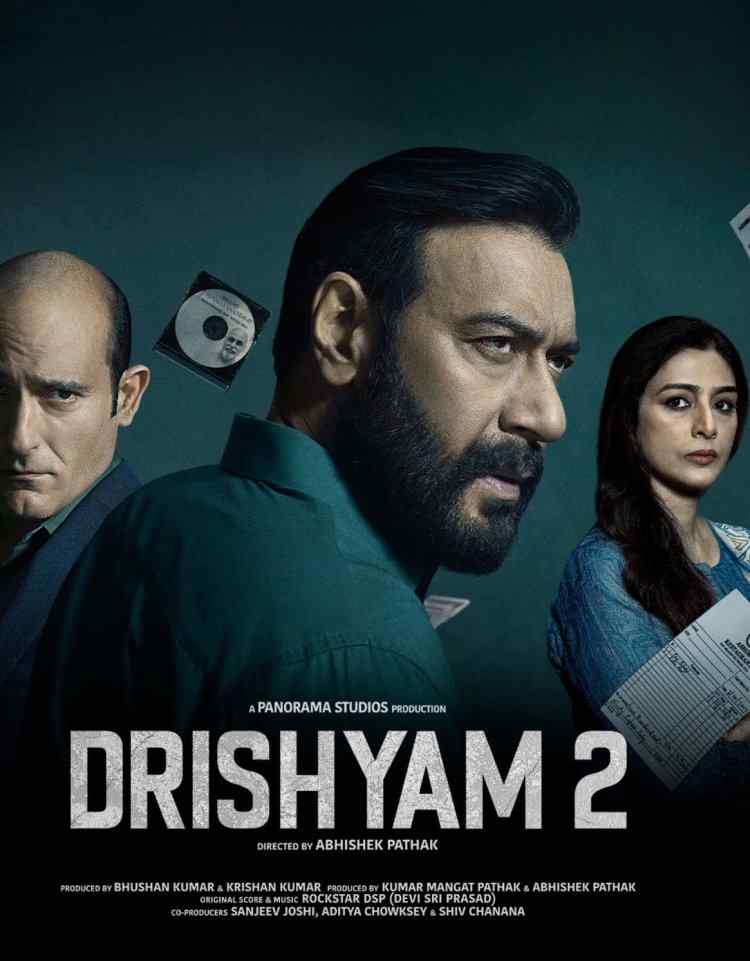

The policewoman’s uniform is an official acknowledgement of her professional identity. The best example in recent times is in the film Drishyam where Tabu plays the role of the IGP. Her uniform is a bit too tight for comfort but attractive for the camera. The portrayal of this woman IGP as shown in the film depicts a gross misuse of administrative powers by the woman whose official duty as IGP is surrendered to her maternal anxieties. She is openly shown torturing an entire family of suspects whose guilt in her son’s disappearance has yet to be proved. She also commands her juniors to beat up and thrash a little girl and her mother without reprieve. What image of the police force does this film represent and how is it that the Censor Board went to sleep while passing the film with an “A” certificate?

Men in the police force in Hindi mainstream films have often been panned by real officials in the police on grounds of wearing wrong kind of badges on their shoulders, wrong number of badges, wrong kind of uniform and so on. That amounts to misrepresentation of their official designation by virtue of ignorance. Lack of a technical and official adviser is the reason for these inaccuracies which lead to an insult and abuse of the police force in films. This also misinforms the audience about these important details.

In recent times however, the sun seems to shine brightly on films even if they are crassly commercial, present courtroom scenes with more seriousness and less with an eye on the box office.

No One Killed Jessica (2011) directed by Rajkumar Gupta. This film did not beat about the bush about being a celluloid portrayal of the infamous Jessica Lal murder case reopened after more than a decade under public pressure through millions of SMSes sent to satellite channels. Gupta has tried to show how in most cases, criminal lawyers are helped by the entire system that helps tamper original evidence in order to protect the accused who was the son of a powerful political personality.

Shahid (2013) is based on the true story of controversial human rights lawyer Shahid Azmi, who was gunned down in cold blood in 2010, presumably for defending a 26/11 accused, who, as it turns out, was acquitted in 2012. The real life Shahid Azmi had defended the 2004 film Black Friday in the courts while it was languishing with the censor board for its controversial content. Anurag Kashyap, the director of Black Friday, went on to co-produce Shahid directed by Hansal Mehta.

While defending Faheem Ansari in the 2008 Bombay Attacks case, he was shot by two gunmen in his office and died on the spot. Later,the innocent Ansari was acquitted of all the charges by the Supreme Court of India due to lack of evidence. In real life, nearly all the accused that Azmi represented were held on false or forced confessions and zero evidence.

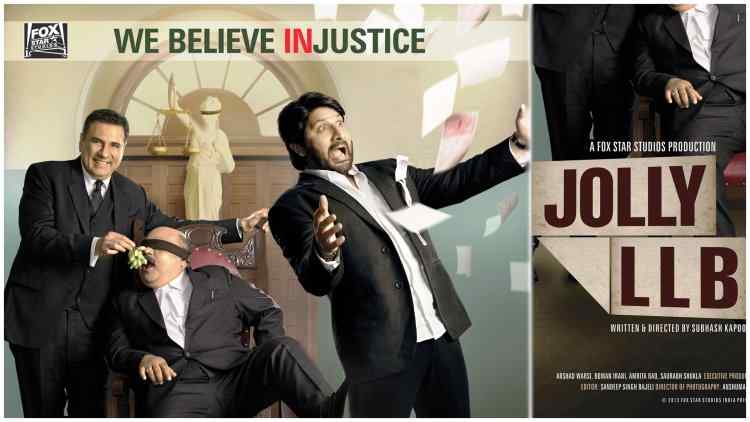

Jolly LLB (2013), written and directed by Subhash Kapoor, was inspired by the real life case history of the infamous Sanjay Nanda-BMW hit-and-run case in Delhi in January 1999. The courtroom scenes are intercut with the trials and struggles of a new lawyer Jagdish Thyagi or Jolly who fights his first case against a very established and arrogant lawyer (Boman Irani) to get justice for the six pavement dwellers, who lost their lives but their killer was set scot-free by the trial court. The film won the Best Hindi Feature Film Award and the Best Supporting Actor Award for Saurabh Shukla at the National Film Awards the following year.

The representation of the court precincts, the supporting staff of typists, small-time lawyers looking for a case, the arrogance of an established lawyer who throws his weight around within the courtroom, the seemingly lackadaisical attitude of the judge sitting on the case, including the skeletal police bodyguard provided to Jolly who takes prompt action when the time is right are depicted with authenticity and conviction.

Court (2015) won the ‘Best Feature Film’ Award at the 62nd National Awards 2015. Court won best film in the Orizzonti section as well as the Lion of the Future ‘Luigi de Laurentiis’ award for a debut film. Chaitanya Tamhane, 27, who directed the film, calls Court a “complete subversion of the courtroom genre”, is perhaps one of the finest expressions of Indian cinema in recent times. It takes on the country’s broken judicial system with a Dalit singer-activist in the centre, and has been filmed with a largely non-professional cast and crew painstakingly handpicked from streets, government offices, hospitals, banks and so on.

The title Court is almost misleading, in the sense that it is extremely distanced from the metaphorical meanings that attach itself to any film presenting any ‘court’ on celluloid. More so, the visual images are far removed from what we recall from our traditional cinematic experience of a ‘court.’ The film repeatedly draws attention to protracted legal proceedings that adversely affect ordinary citizens both mentally and financially. Tamhane lets the film speak for itself and underscores the lacunae in the legal, the police and the judicial systems as they stand today and have stood for decades.

Ethical questions about choosing real life stories to place on film remain. Should a filmmaker really make a film on the rape of a teenaged girl by a famous and popular Godman? India is a democracy where the Constitution grants us the right to freedom of expression. So one cannot deny a filmmaker making a film on a delicate real-life case because that would amount to censoring a concept much before it has been made into a film. This can be encouraged not for sensationalising a real life tragedy but for the way it leads to greater information, perpetuation of knowledge about the people involved and most importantly, to uncover ugly truths of life that reveal how power works in the largest democracy of the world.

***

What's Your Reaction?