A WRONGED KASHMIRI WOMAN JOURNALIST AND THREE FILMS ON KASHMIR

In her scholarly writing, Dr. Shoma A. Chatterji has conducted an in-depth examination of a collection of films, consisting of two documentaries and one feature film. These films together explore the socio-cultural circumstances surrounding women and girls in the region of Kashmir.

Who is Safina Nabi? She is an independent journalist from Kashmir whose award was cancelled at the last minute. She writes about gender, health, human rights, social justice, development, and the environment. She has written for publications and organisations such as Women Under Siege, Nikkei Asian Review, Ours to Save, The New Humanitarian, Himal, The News Lens, The Print, BBC Urdu, and Article 14, among others. As a Pulitzer Grantee, Nabi has written not only on half widows but on other serious topics as well. One example is – India’s Grand Plans for Kashmir Dams, among others.

She has focused on the half-widows in Kashmir, a fact that is a global truth no one can deny. Half-widow is a term given to Kashmiri women whose husbands have disappeared and are still missing during the ongoing conflict in Kashmir. These women are called "half-widows" because they have no idea whether their husbands are dead or alive. Thousands of husbands in Kashmir disappeared during the conflict. They do not know whether their husbands will return or not so they dare not marry again for fear of the husband returning suddenly.

And for these series of articles, published across several media, she was one among the three awardees chosen by a select jury for the ‘Journalism for Peace' award by a private educational institute in Pune. The other two awardees are - Tora Agarwala and Sonal Pateria.

On October 16, a day or two before the scheduled programme, she was informed that the award was being withdrawn and that she needed not travel to Pune. She was informed that the award had been cancelled due to “alleged political pressure and threats from various political groups.”

And what does the term “political pressure” really mean? And “threats”? What kind of ‘threats’? Threat to the lives of the organisers? Threat to the life of the awardee if she were to land in Pune to accept the award in person? It is presumed that Nabi’s continuous foray into gathering rather sad facts about a large number of women and children in Kashmir through her articles right across the globe must have raised the hackles of some of the sponsors. Despite Nabi’s request for communication in writing the institute’s director, Dhiraj Singh, the director, did not provide any written information. He told her, “We are an institution and, at the end of the day, this is a business. You have to understand our point also. You know the atmosphere in the country.” Note the use of the word “business.” If these awards were part of a ‘business deal’ with some of the sponsors, then the award is neither neutral nor objective and therefore, holds little value. So Safina Nabi need not feel insulted.

This writer would like to offer a looking back to three films, one a feature film and two documentaries, which clearly deal with the oppressed women of Kashmir over decades.

There Was a Queen (2007)

This is a long documentary jointly directed by Kavita Pai and Hansa Thapliyal. It is called There was a Queen "Difficult ethical questions are a part and parcel of documentary filmmaking," says Kavitha Pai who, along with her friend and peer Hansa Thapliyal, were commissioned by Other Media, an NGO that functions in Delhi and Bangalore, to make a film on Women, War and Peace in general, and in particular on peace initiatives by women in conflict-ridden states. The outcome is a 105-minute incisive documentary called Yi As Akh Padshah Bai (There was a Queen) on peace initiatives by the women in Kashmir, in conflict-ridden areas not read much about in the media.

Alongside the women who come across with very powerful voices, we find the camera closing in on some men. One of them is a former militant; a second man had sent his son for training across the border with his blessings. The third man is a school master who lost his son in gun battle only to realise that he was a militant. The fourth is a schoolboy whose brother was killed in crossfire. And as they spoke to the men, they realised there is a difference in the narratives of men and women.

There Was a Queen is a film of conflict and peace in Kashmir. It is about Kashmiri women who talk openly about terrorism, militarism, peace and their daily life. It is a record of political voices of women representing many sides in Kashmir. While documenting the plight and pluck of women, the film demonstrates the uncertainty of the everyday lives of young girls and women whose lives could be trapped in a no-exit situation at any moment, without dramatising this constant risk. A young girl learning tailoring in the Zainab Skill Centre in Maisuma in the heart of Srinagar, is being teased by her friends for wearing lipstick. She says, "Who knows whether I will remain alive tomorrow? So, why not fulfill my desire and have some fun while I am alive today?"

The crew reached Sopore two days after two young girls Shahnaza and Ulfat, both 17, studying in pre-university were killed. Kavitha Pai says that they did not wish to shoot the funeral of the two girls because it would be intruding into very private moments of grief. "But the family insisted that we do, because they wanted the rest of India to know what was happening in Kashmir. As one of the dead girls was being bathed by her wailing mother, I could not bear it anymore and Hansa took over. 'Did you see the mehendi in her hands?' Hansa asked me afterwards. I hadn't because I felt guilty in some way," says Kavitha.

The documentary not only traces the plight of the women, but also shows the video footage of the movement of the convoys of security forces personnel in busy areas of Srinagar city. Parveena Ahamgar, whose son is missing, and Parvez Imroze, a lawyer who works in the area of human rights founded the Association of the Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) in 1994. The APDP is an important initiative by women towards bringing peace to Kashmir. Tasleema Bano, a resident of Malangam-Bandipora and a member of APDP said how her husband was picked up some years ago, and has never been seen or heard of again.

Women who have lost their near and dear ones are united in carrying forward a joint struggle, demanding the return of their missing husbands, sons, brothers and fathers. "If they are dead, give us their dead bodies so that we can give them a decent burial," says one woman. These women are neither involved in the political issues that plague the state, nor are they part of militant groups. Their tragedy is that the male members of their families have been picked up either by militants to join the movement for Azaad Kashmir, or by the security personnel, or by the Indian Army.

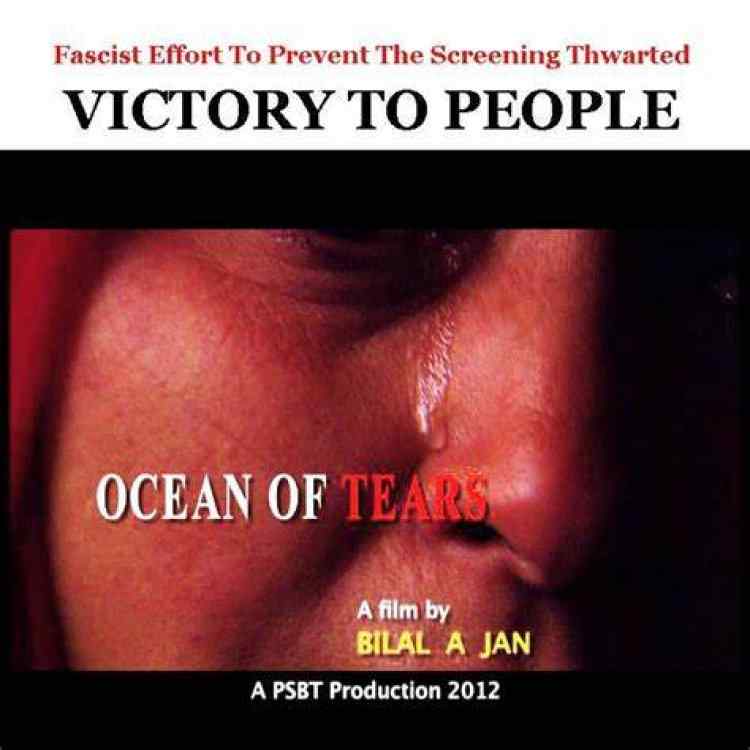

Ocean of Tears (2012)

Woman is a ray of God

Not a mere mistress.

The Creator’s Self, as it were,

Not a mere creature.

These lines from a poem by Jalal Uddin Rumi fill the opening frame of the documentary Ocean of Tears by Bilal Jan. To Bilal Jan goes the credit of bringing this dark phase of the history of gang rape used as a form of violence by an army for the first time. Ocean of Tears, produced by Public Service Broadcasting Trust gives us a bizarre insight into the administrative, legal and judicial apathy these women are victim to. The gang-rapes and the killings, murders and forced disappearances are one side of the story. The other side is darker, scary and inhuman – the Indian Government’s attempts to either hide or whitewash the truth of these violent acts instead of punishing the offenders who belong to the military forces – the Army, the Rashtriya Rifles, or the CRPF. Militants too might have been involved but most of these atrocities on women are said to have been done mainly by the different military outfits of the Indian defence services.

The film travels back to the gang-rape of 32 women in the village of Kunan Poshpora in Kupwara District, J & K that took place on February 23 and 24 in 1991. According to the villagers’ statement and newspaper reports, around 40 women and children were gang-raped. It had snowed that day and the paths were covered with four feet of snow. At 11.00 pm, the crack-down began. The men were dragged out of their homes and forced to remain on the snow-covered paths outside. Youngsters were taken to the torture camps and the women and girls were raped and beaten so much that most of the men could hardly recognize their own wives the next morning. The rapists, soldiers all, were from Panzgham camp.

The camera captures a group of angry husbands twenty years later, seated in a semi-circle narrating their tales of despair and anger. Four of the victims died because of excessive bleeding. Some of them are still getting treatment. Zareefa died of excessive bleeding leaving behind six unmarried daughters. Zoona, Rafiqa and Sara had to get their uterus removed. Sara says she has to spend Rs.8000 to Rs.10, 000 on medicines. Though the men approached the Brigadier of the nearby camp, the Superintendent of Police and the Corps Commander of Army who came to take the statements of the victims and the men, nothing happened. A FIR was finally registered after Wajahat Habibullah, the then Divisional Commissioner of Kashmir, intervened, and a case of gang rape was registered against the Rashtriya Rifles of 68th Brigade who had entered the village and committed the heinous act. But the government of India refuted the claims of the complainants because the FIR was lodged three days after the event. How could the victims file a FIR when they were held captive by the soldiers and the women were not even able to walk and talk?

There was a Queen, which leaves us with strange feelings of shock and guilt - shock because of the meaningless death and disappearance of hundreds of people, and guilt because so many of us have done nothing to help these women who are trying to carve out pockets of peace in their disturbed lives. The conflict has created a large number of widows, 'half-widows' (those whose husbands have disappeared), mothers who have lost their sons, daughters who have been subjected to rape, women pushed out of employment and people suffering from acute stress and trauma. The sheer banality of such acute suffering is striking, throughout the film.

Harud (2020)

Harud narrates the tale of war-torn and strife-ridden Kashmir as seen through the eyes of its director, Aamir Bashir. It is also a point-of-view film from the perspective of its protagonist Rafiq who offers a microcosm of today’s young Kashmiri groping with the constant fluxes in his relationship with his parents who refuse to accept that the older son Tauqir, is dead and will never come back. “It took four years for me to translate it from script to film. It was the entry of mobile phones in Kashmir in 2003 that triggered the idea of portraying the insecurity the people are living under. I wished to explore how this has had a telling effect on the psyche of the Kashmiri people resulting from violence of around 20 years,” says Bashir about his first film. “I am a Kashmiri myself and am a first account witness of the transition of Kashmir from my boyhood days. I do not find Kashmir very truthful today. The idealistic Kashmir existed only in my boyhood. I have tried to look at Srinagar through a social perspective rather than through a political one,” he adds.

The film speaks more through its ominous silences and carefully structured sound design than through words. Local musical instruments such as the oud can sometimes be heard on the soundtrack along with the viola. The silence is dotted with ambient sounds – screeching tires of moving buses that sound very much like sounds of ammunition being fired, the soft whimpering of a tiny child, the sound of a bomb exploding in a street kabab shop, the sound of Rafiq’s clicking camera. Rafiq’s ambitious friend who goes to Delhi to take part in a reality show provides relief in the bizarre reality. The exploitation of the past where someone tries to make a fast buck by trying to pawn off a picture of “Azad” Kashmir clicked in 1947. Photographers with their video cams and satellite news journalists try to extract newsbytes out of the collective tragedy of an oppressed people. As the film moves along spreading its message of fear, one realises that the chinar leaf has outlived its presence in the film which makes its own statement.

In Harud, which means “autumn”, autumn is not just the season it stands for. It is a metaphor for a state caught in a situation of persistent siege, bomb blasts, and killings and of young men walking across the wire fencing that divides India from Pakistan to become militants. It stands for an eternal, never-ending time and space within which the people of Kashmir are trapped. It is a no-exit situation where you die if you are a militant, you die if you are not, and those who live, do not know about their dearest ones lost on the horizon. The falling leaf of a saffron colour Chinar tree is a repeated metaphor. It is as if the russet and the red and the crimson of the chinar leaves have spilled over on to the lives of these innocents, seen through blood and death and loss.

Asked what motivated him to make such a disturbing and thought-provoking first film, Bashir says, “the handful of films on Kashmir that have been made after the insurgency in 1989 were told from an outsider’s point of view, part of a colonial discourse where there were good, peace-loving Kashmiris polarized from some black sheep who had gone astray. The films played out the typical mainstream formula of good versus evil counterpointing the hero against the villain. My team and I decided to give an insider’s perspective. Maybe, this was contrary to the mode followed by mainstream cinema but once the decision was made, we stuck to it. The 55-page screenplay took three to four long years to settle down and the entire process was a distillation of the Kashmiri experience in the last two decades.”

These films were screened more than a decade back. If these films were screened right across film festivals across the globe, why can’t Safina Nabi get the rightful award bestowed on her because she wrote a series on the half-widows of Kashmir?

***

What's Your Reaction?